2050 Today examines what needs to happen today to decarbonize the global economy by mid-century and avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The last decade has had a mixed legacy for climate change. The earth witnessed its five hottest years on record, global emissions are at an all-time high, and we saw inaction and lack of commitment from governments all around the world. But we did see civil society step up in a big way – a grassroots movement of youth mobilized millions on the issue of climate change, renewable energy finally became cheaper than fossil fuels, and new technology and research have shown us that there are pathways, there are policies, and there are people all around the globe committed to ending the climate crisis.

So how can we make this decade the one of climate action? What is our goal?

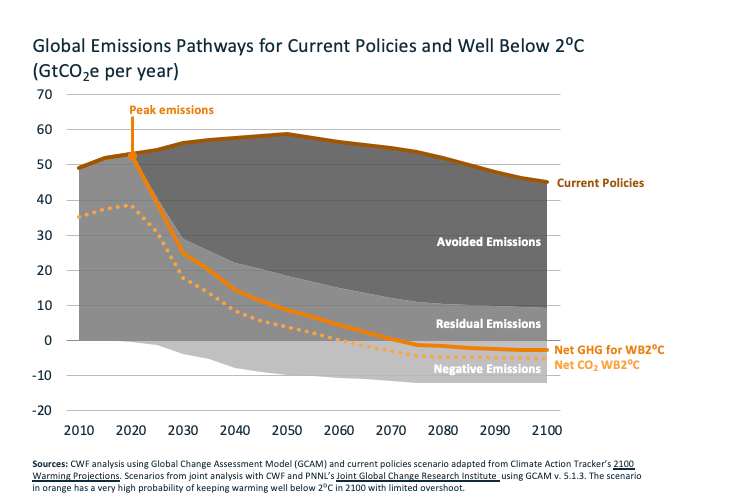

The consensus from global climate scientists and researchers is that we need to see emissions peak as soon as possible and significant emissions reductions by 2030, but then also to drive global carbon emissions down to net-zero by mid-century to ensure the world stays well below a 2°C rise in global temperatures.

The consensus from global climate scientists and researchers is that we need to see emissions peak as soon as possible and significant emissions reductions by 2030, but then also to drive global carbon emissions down to net-zero by mid-century to ensure the world stays well below a 2°C rise in global temperatures.

And how do we get there?

We have to both accelerate near-term solutions that are ready to be scaled now (think electric vehicles, retiring coal power, shifting public and private capital away from high carbon infrastructure), and also test out and promote emerging strategies and new ideas that will be crucial in the long run. We have to find ways, for instance, to remove 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year directly from the atmosphere, so we need to find cost effective and scalable solutions now to be able to meet this removal target by 2050.

This thinking led us to launch 2050 Today, a ClimateWorks initiative that takes a long term planning horizon and seeks to tackle harder to mobilize areas in climate mitigation. Our goal is to bring together a community of experts to develop and test out new strategies, and then to mobilize philanthropy to invest and scale them to the next level.

We kicked off 2050 Today in 2018 with a convening of more than 100 experts from research, philanthropy, academia, industry, and public office. Coming out of this meeting, we progressed in a number of areas:

- The Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) Fund, which built from five initial seed grants in 2018 to having since raised $27M to advance, finance and advocate for a portfolio of carbon removal approaches ranging from nature-based solutions to tech heavy ones.

- We hired a food and agriculture strategist to steer us on the issue of land-use, food consumption and agricultural practices.

- With critical input from all our partners, we have also been developing key strategies to electrify freight and shipping and,

- We have homed-in on finding pathways to make the aviation sector carbon-neutral.

We are continuing this critical work with the next 2050 Today event to be held in April, 2020. It will bring together and tap into the expertise of NGO partners, scientist and policymakers to test areas of exploration, including:

- Sectors that are unlikely to fully electrify but are poised for other kinds of solutions (cement and steel production, long-haul aviation, shipping, offroad equipment, etc.),

- Effective theories of change for engaging in high-growth regions and geographies (e.g., Indonesia and Africa),

- Pursuing strategies that can catalyze structural transformations of economic and social systems to end the climate crisis.

Below are examples of the key themes we will explore at the event.

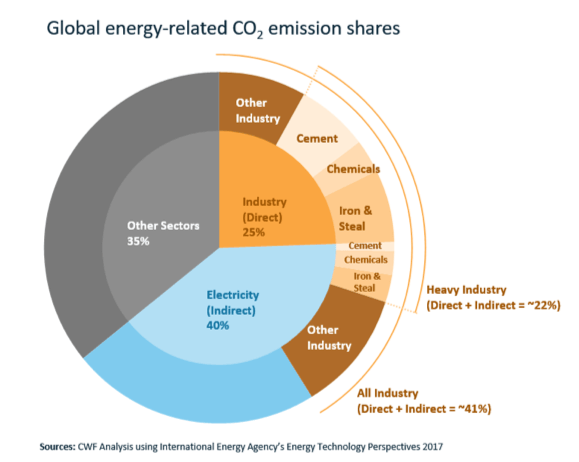

Exploring alternatives for heavy industry

The industrial sector (including steel, cement, chemicals production) generates about forty percent of all energy-related carbon emissions. Like other sectors, industry needs to approach net-zero emissions by mid-century to meet international climate goals. To catalyze this deep decarbonization, we are pursuing strategies like material efficiency, material substitution, and process change. We need to use smaller amounts of higher quality materials, substitute high-emissions materials like cement and steel with lower emissions alternatives like timber, and scale up low- or zero-emissions production processes. We need policies that will make low-emissions alternatives profitable, like public commitments to buy low-emissions materials, codes and standards, and investments in commercializing new technology.

The industrial sector (including steel, cement, chemicals production) generates about forty percent of all energy-related carbon emissions. Like other sectors, industry needs to approach net-zero emissions by mid-century to meet international climate goals. To catalyze this deep decarbonization, we are pursuing strategies like material efficiency, material substitution, and process change. We need to use smaller amounts of higher quality materials, substitute high-emissions materials like cement and steel with lower emissions alternatives like timber, and scale up low- or zero-emissions production processes. We need policies that will make low-emissions alternatives profitable, like public commitments to buy low-emissions materials, codes and standards, and investments in commercializing new technology.

Pursuing climate mitigation in Africa and South East Asia

Africa and South East Asia are currently fast-growing economies, with rapid population growth. As we look ahead to 2050, these two geographies become increasingly important areas for sustainable development and climate action. New investments into fossil-fuel based energy and other high-carbon infrastructure projects have the potential to accelerate and lock in significant emissions through mid-century. Yet there is also a huge window of opportunity in this decade to support emission reduction efforts in these geographies with the potential to boost economic and/or social development while increasing productivity and reducing poverty, unemployment, and inequality.

Understanding the role of behavior and shifting consumer patterns

Behavioral science has much to teach us about how to make climate strategies more effective. We are beginning to better understand how deep, systemic change really happens, using insights from psychology and cognitive science. This includes grappling with complex questions, such as how to ensure low-carbon consumption changes are positive rather than punitive, and how to scale from individual low-emissions choices to broader societal behavioral changes.

These preliminary themes are a starting point for further exploration, together. There are more questions than answers at this point, reflecting the thorny nature of the challenge ahead. 2050 Today is a collaborative effort to surface key questions about what an expanded planning horizon implies for climate mitigation philanthropy. We recognize the urgency to act boldly and collaboratively today to make net-zero emissions by mid-century a reality.

It was a feat to have COP25 organized in a new city within a month. But results fell short of even moderate expectations, and the contrast with the public energy and expectations on the street is stronger than ever. Fortunately, many initiatives took advantage of the convening opportunity to advance their agendas, including several that ClimateWorks highlighted during the COP.

COP25 in Madrid was both impressive and underwhelming. It was remarkable that Spain and the city of Madrid managed to put it together so quickly — the venue looked like a normal COP, with pavilions and side events all in place as usual. Excellent public transportation made it easy to get around, and the city rose to the occasion, even staging a climate march with hundreds of thousands of participants.

Less encouraging were the process and outcome of the negotiations, which ran deep into overtime in an effort to salvage an acceptable text. Negotiations on carbon markets, Article 6, failed to reach agreement, and clear signals on ambition were few and far between. The two “Chile Madrid Time for Action” decisions (from the COP and the CMA) fall far short of the urgent commitments the thousands of people on the street are calling for.

The results paradoxically mean there’s both even more emphasis on COP26, and a continuing need to ensure public pressure, while not overemphasizing the role COPs can play in combating the climate crisis.

ClimateWorks at COP25

ClimateWorks and its partners took advantage of the COP to present several activities and to convene project meetings, with significant outcomes:

- The CAMDA initiative, which unites those quantifying the contribution of regions, cities, businesses, and investors to climate outcomes, convened 30+ organizations for two days. As a result, the UNFCCC secretariat committed to work toward integration of CAMDA’s results into the Marrakech Partnership on Global Climate Action, whose mandate was renewed by the COP. The COP decision included language supporting the role of non-state actors and the NAZCA portal.

- The Independent Global Stocktake (iGST) presented its recent work at two side events and held a consortium meeting, which came on the heels of the launch of a series of discussion papers on how to design a robust Global Stocktake (GST). Plans for 2020 include broader outreach globally and further elaboration of gaps identified in the GST.

- ClimateWorks and the Pisces Foundation catalyzed the creation of the “Madrid Call for Fast Action on Super Pollutants,” which was launched by the World Resources Institute, Environmental Defense Fund, and ClimateWorks at the COP. The document, produced with the cooperation of dozens of experts in the field, identifies cuts to super pollutants as the primary means of slowing global warming in the coming decades, and calls on countries to devise Fast Action Plans on super pollutants to include in revised nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement that they will present in 2020.

- Principles for Responsible Investors (PRI), a U.N.-backed group of investors worth $86 trillion (also supported by ClimateWorks), released a report detailing the financial losses that polluting firms are likely to face, and the uptick that clean companies will see in their overall value. This report landed with significant media coverage, including from the New York Times and the BBC, and adds to the growing pressure on big businesses to transform their practices and move away from fossil fuels.

The Road to Glasgow

COP26 is a moment when various strands should come to resolution: long-term strategies, enhanced NDCs, and the holdover of COP25 negotiations on Article 6 carbon markets, governance for loss and damage, common timeframes for NDCs, and other items.

Expectations for 2020 are high, giving COP26 a sense of elevated importance.

But to be successful, it has to match the urgency we’re seeing so many people communicating at a large scale around the world, a phenomenon that needs to see results if it is to maintain momentum.

Part of the answer is for countries to step up and deliver as expected; part is seeing the U.N. system and COPs evolve to make the best use of time and find venues that advance important issues, from accounting for non-state action, to preparing for and preventing climate disasters; and part is about continuing to diversify the targets of popular energy at all levels of governance, from the bottom up. It’s a big agenda for 2020, and ClimateWorks is proud to be working with such a thoughtful and energetic community to keep pushing forward.

By signing the Paris Agreement, countries agreed on long-term goals backed by national plans that are collectively reviewed every five years. This process, known as the global stocktake, is key to increasing ambition.

Think of the stocktake as a regular check-up for the Paris Agreement. It assesses the health of collective efforts to:

- Reduce emissions;

- Build resilience to climate change; and

- Align financial support with the climate action that is needed.

So what’s the diagnosis? Based on the latest scientific updates, not good. We are on a course to warm the planet between 3 and 4 degrees C (5.4 and 7.2 degrees F) by 2100 and the past five years were the warmest ever recorded. Rising seas, increased storm surge, tidal flooding, droughts, forest fires and extinction of coral reefs show how climate change is affecting our planet. Climate change could directly cost the world economy an estimated $7.9 trillion by 2050 due to increased drought, flooding and crop failures. These and other symptoms require an emergency response — not just to triage the most severe impacts, but also to unlock the $26 trillion in economic benefits that bold climate action could provide by 2030.

Countries are expected to come away from the stocktake with a thorough diagnosis and suite of options to improve the health of collective and individual climate change actions. Transparency, analysis and accountability are expected to spur countries to accelerate and enhance their climate action and put the world on track to avoid life-threatening temperature rise.

What Happened at COP24 in Poland?

In Katowice, countries agreed to three phases of the global stocktake:

- Collecting and preparing information to take stock of progress. In 2022, the information collected will include the latest nationally determined contributions (NDCs), the latest scientific findings from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and reports from individual countries on their progress to achieve their commitments under the transparency framework.

- Technical assessment period. This is a review of the information collected to suggest the best course of action, through a series of in-person dialogues over the course of a year during UN climate conferences.

- Communicating and acting on findings. By the end of 2023, key findings from the assessment will be presented to high-level country representatives. Countries will then know how much progress has been made and can determine what this means for further stepping up national and collective climate action.

At last year’s COP24 in Katowice, Poland, countries agreed that to meet the goals of mitigation, adaptation and finance, they will also consider efforts to minimize and address inevitable climate impacts — known to climate negotiators as loss and damage — and any unintended social and economic consequences of these responses. However, there is as yet no clear path to incorporating these efforts into the global stocktake. While collective efforts are expected to be assessed based on equity, there is no common understanding of what exactly equity means or what benchmark should be used to evaluate global efforts.

What Countries Still Need to Decide

Last year’s decisions omitted details that must be addressed to make the process effective. Beyond the rough timeline from 2022 to 2023 for the first global stocktake, there needs to be more clarity on how the information is prepared and to ensure that it is made available at an appropriate time, and that the results of the assessment are fully communicated to each country’s policymakers. The third phase must be concluded in a timely manner to influence national political agendas regarding the development of subsequent NDCs, due in 2025. What the output of the collective assessment would look like — perhaps a summary report — should also be further defined.

To spur enhanced action, the international and national decision-making processes should be informed by sharp analysis, benchmarking and advocacy. While the global stocktake is driven by national-level action, non-state actors, including cities, states, businesses and civil society contribute to the process by providing valuable information, analysis, tools and opportunities to pave the way for the needed transformation.

This is where civil society-led initiatives such as the independent global stocktake (iGST) come in, laying the groundwork for the important task ahead rather than waiting for the global stocktake to take place. The iGST is a data and advocacy initiative that brings together climate researchers, modelers and advocates from around the world to support increased ambition within the Paris Agreement. It also enhances the credibility of the process by holding countries accountable and contributing to more accurate and transparent data, process and outcomes.

Since the first global stocktake isn’t due until the end of 2023, it will not be on the agenda of this year’s COP25 in Madrid. However, planning ahead is key to making sure that the process delivers on its promises. The iGST will aim to share views during COP25 and in the months ahead on how to make the global stocktake effective and ensure that relevant research and analysis informs the outcome.

The series explored the potential contours of the Global Stocktake (GST) through the lenses of each of the Paris Agreement’s three long term goals - mitigation, adaptation, and finance, with equity as a cross-cutting consideration.

Over the past month, ClimateWorks Foundation hosted the independent Global Stocktake (iGST) webinar series, “A Vision for a Robust Global Stocktake,” which explored the potential contours of the Global Stocktake (GST) through the lenses of each of the Paris Agreement’s three long term goals – mitigation, adaptation, and finance, with equity as a cross-cutting consideration. As we wrap up the series and look toward COP 25 and 2020, we wanted to reflect on what we learned.

Over the past month, ClimateWorks Foundation hosted the independent Global Stocktake (iGST) webinar series, “A Vision for a Robust Global Stocktake,” which explored the potential contours of the Global Stocktake (GST) through the lenses of each of the Paris Agreement’s three long term goals – mitigation, adaptation, and finance, with equity as a cross-cutting consideration. As we wrap up the series and look toward COP 25 and 2020, we wanted to reflect on what we learned.

What can we expect from the GST?

The three webinars presented information on the data sources and coverage expected from the GST. They also began to suggest complementary roles for the iGST.

- Mitigation (presented by The University of Maryland Center for Global Sustainability): mitigation-related indicators run the gamut from techno-economic to more qualitative and diffuse. The GST’s mandate is to take stock collectively, which means complementary processes are necessary to get to the national level. In general, it is easier to obtain and summarize the quantitative information and harder to obtain and summarize qualitative information. While it is not clear exactly what will be included in the official GST, it is likely to focus on quantitative indicators explaining the questions of ‘where are we?’ and ‘where do we want to go?’. Partners proposed that the iGST focus on sharpening our understanding of barriers, capacity, and enabling conditions, issues that are really at the heart of ‘how do we get there?’ but are less well synthesized at present. Full notes can be accessed here.

- Adaptation (presented by the UNEP DTU Partnership): the data sources feeding into the GST are defined as the UNFCCC country submissions (including Adaptation Communications, Biennial Transparency Reports, National Adaptation Plans, and National Determined Contributions, all to be compiled in a synthesis report), IPCC reports, and other sources. In general, these data sources are flexible rather than mandatory, contain little standardized information fit for aggregation, and occur on timelines that may not align with the GST. The currently defined data sources are unlikely to meet all the four functions of the GST for adaptation, as defined in Article 7 of the Paris Agreement. We can, however, expect the GST to include nationally relevant, qualitative data on the state of adaptation efforts, experience, and priorities at national level. The iGST, meanwhile, can potentially contribute by clarifying what to track, proposing how to track it, and addressing empirical issues. Full notes can be accessed here.

- Finance (presented by the Overseas Development Institute): the GST will include the latest information from the Overview of Climate Finance Flows (Biennial Assessment), which includes information about the $100b per year pledged by developed countries to developing countries, the breakdown of public spending between mitigation and adaptation, aspects relating to the effectiveness of finance, and some information about whether economy-wide financial flows are consistent with Paris goals. Other inputs to the GST include voluntary submissions from parties, relevant reports from regional groups and institutions, and submissions from non-party stakeholder and UNFCCC observer institutions. Within this landscape, the iGST could help fill data gaps around issues like domestic finance; work to harmonize understanding on difficult topics like loss and damage finance and consistency of finance with Paris Agreement goals; and/or support understandings of finance at the national and sectoral level to bolster the ambition of NDCs. Full notes can be accessed here.

Webinar recordings are available upon request.

How might the independent community help with stocktaking?

One goal of this webinar series was to create active dialogue with our broader community. Through these discussions, we continued to add nuance to our understanding of how the iGST can complement the existing landscape of initiatives and began to clarify essential equity considerations, critical issues that deserve blog posts of their own but that we’ll only mention briefly here. Importantly, we also thought more about the future direction of iGST work. Here is a trifecta of takeaways on that subject:

- The iGST can help cross-walk between national and international: The GST is bound to be collective, but benchmarks could still help make it nationally relevant, and both beforehand and in the wake of each GST there is space to make national actions more ambitious and effective. National and international efforts bolster each other via a complex interplay, but ultimately most action ‘comes to ground’ on national and sub-national levels. Toward this end, advocates emphasized that they would like information that allows them to better assess the ambition of individual countries and identify where they can increase ambition. There was a suggestion that the international stocktake could be paralleled with national and city-level versions. We’re still figuring out exactly how the iGST engages on the national, regional, and/or sectoral levels, but this is an area where we’re hoping to build further next year.

- We need not shy away from difficult issues, i.e., including uncertainty of temperature rise: Beyond just targeting ‘low-hanging fruit’, respondents emphasized that the iGST could potentially leverage its independence to help build clarity on difficult issues unlikely to be included or even acknowledged in the GST, such as how to achieve a 1.5 degree world; the implications of negative emission technologies; adaptation under various temperature scenarios, including those that may exceed the <2 degree goal; and harmonization of understanding of tricky finance issues like loss and damage finance and climate-aligned finance. While we aren’t likely to solve these underlying issues, we may be able to foster conversation and build alignment.

- There’s less familiarity on adaptation and finance: There has been less collective thinking on adaptation and finance within the Global Stocktake frame compared to mitigation, yet all three will be critical to the success of the GST. In the case of adaptation, this may in part be due to data availability challenges. Yet it would be a shame if these topics got shortchanged in stocktaking exercises as a result of lack of data or interest from the independent community, particularly when impressive partner initiatives like the Global Adaptation Mapping Initiative (GAMI) are working hard to fill data gaps.

The bullets above touch on issues that are far larger than the iGST. Yet rather than let the scale and complexity of these topics daunt or distract us, our hope is to leverage the iGST as one strategic frame from which to address these issues, much as we hope the GST can serve as a galvanizing force in the Paris Agreement. We’re excited to work with the broader community to keep learning.

The iGST is an important initiative for ClimateWorks that unites the analytical and advocacy communities to ask the hard questions around what it means to connect the many dots between knowing what we need to do, and figuring out how we do it.

The Paris Agreement outlines a five-year cycle of evaluation (through the Global Stocktake) and new climate commitments (through enhanced nationally determined contributions, NDCs). With the first GST taking place in 2023 and new NDCs being announced in 2025, that means there are only five 5-year periods remaining until 2050, when the world needs to be within striking distance of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. Considering that every inch of policymaking progress is extremely hard-won, it is a seismic shift from the normal course of politics to be at the point where every decision has to yield a maximum outcome.

ClimateWorks and its partners launched the independent Global Stocktake (iGST) at COP24 to make sure these five 5-year cycle are maximally effective. We’re laying the groundwork now to do two things: push countries to get as much as they can out of the GST, and to accompany that process by enhancing those elements that inevitably won’t be covered. The iGST is an important initiative for ClimateWorks that unites the analytical and advocacy communities to ask the hard questions around what it means to connect the many dots between knowing what we need to do, and figuring out how we do it.

One partner, the World Resources Institute has reviewed the key considerations for how the formal UN process can yield as robust, effective, and inclusive a Global Stocktake as possible. Wuppertal Institut is taking a step back to ask the question, what would an ideal Global Stocktake look like, in terms of its function within a global agreement? The iGST consortium recently presented the current status of ongoing research that digs deeper into the means by which the GST can be made most effective; consortium members will present this work at COP25 in Santiago. Our discussion identified several areas for further research to inform the iGST workplan:

- Previous attempts to take stock of international agreements and encourage greater action have had mixed results. For example, the Talanoa Dialogue was structured around meaningful and interesting questions (where are we now, where are we going, how do we get there?), but it only yielded a non-committal call for action. Nevertheless, the Dialogue did help drive political attention around the IPCC 1.5 Special report, which was very influential. In the future the relationship between the GST and IPCC assessment report could be similar.

- The GST is a state-led process, but we have seen new research, methodologies, and analysis around the impact of non-state and sub-national actors, showing how their climate action helps countries meet, and in some cases over-achieve, current national pledges under the Paris Agreement. Highlighting this will be an important role for the iGST.

- The all-important question is how assessment leads to action:

- We can balance both ‘shaming’ and ‘faming’ countries, and need to assess where we can see examples of this working well. An example of a recent approach is the new Ambition Call from the ‘Brown to Green’ report, assessing G20 countries.

- There is a growing body of information on emissions trajectories and technologies, so the iGST can focus more attention on the social science and non-quantitative aspect of how progress is made. In Talanoa parlance, ‘how do we get there’ is much harder to answer than ‘where are we now and where are we going?.’ An example of recent work is by Climate Action Tracker on governance.

- The iGST consortium views the GST not as a punitive assessment but as an opportunity for countries to learn, spurring ambition. We will communicate to countries and government delegations that there is an independent community of practice that will be watching, analyzing, and sharing back what we observe around the Global Stocktake. We hope to take advantage of any future regional climate weeks, and to interface with existing initiatives with broad reach.

This fall we are hosting three webinars on each of the main aspects of the iGST – mitigation, adaptation, and finance (registration is available below). Our goal is to share preliminary research on the nature of information available to the GST in each of these areas, as well as to hear from a diverse range of partners on these essential topics:

- Mitigation indicators and analytical approaches for the Global Stocktake. Friday, October 25, 7 – 8:15am PDT/ 4 – 5:15pm CEST.

- Adaptation in the Global Stocktake: the scope for independent input. Thursday, October 31, 7 – 8:15am PDT/ 3 – 4:15pm CET

- Understanding finance in the Global Stocktake. Thursday, November 7, 7 – 8:15am PST/ 4 – 5:15pm CET.

ClimateWorks is making sure that it is proactively addressing its own climate impacts and is helping to make the aviation industry part of the climate solution.

In recent months, aviation sustainability has been in the news like never before. Spurred by activists like Greta Thunberg, many travelers have begun to more seriously consider the climate impacts of their jetsetting ways. In Thunberg’s native Sweden, the public has even coined the term “flygskam,” or “flight shame” in English.

ClimateWorks is no stranger to flygskam. As a global organization with programs across the world, the largest contributor to our organizational carbon footprint is by far our airborne business travel. Considering that our mission is to solve the global climate crisis, we are keenly aware of the impact of our own activities and are focused on the role that philanthropy can play in accelerating the decarbonization of the aviation sector.

This is why we are excited to announce that ClimateWorks is a launching NGO partner for SkyNRG’s new Board Now program, which will allow us to support the development and deployment of sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) that can potentially play an important role in reducing the climate impact of the aviation industry.

Board Now has secured voluntary commitments from two companies to fly on SAFs by absorbing part of the cost premium of these fuels, with plans to expand to 10+ companies soon. By aggregating these commitments and securing fuel offtake agreements with airlines to demonstrate demand for SAFs, SkyNRG is on its way to securing financing to build a new production facility for these SAFs in the Netherlands, with production starting in 2022. By making SAFs more widely available and utilized, ClimateWorks and SkyNRG are seeking to accelerate emissions reductions in an industry that is projected to increase its greenhouse gas emissions three-fold by 2050.

While ClimateWorks strives to only fly when necessary, the reality is that long-distance travel remains a necessity in order to maximize the effectiveness of our organization. ClimateWorks leads the world’s only philanthropic strategy to address the climate impacts of aviation and our support for Board Now expands this commitment. SAFs are one of the few near-term ways to reduce emissions from air travel and efforts to accelerate the availability and cost competitiveness of these fuels are urgently needed.

As the world works to confront the rapidly intensifying climate crisis, the projected expansion of the aviation industry in the near future may well negate some of the positive impacts of decarbonization in other industries, unless concerted action is taken. Governments and airlines both have major roles to play in bringing about the transformative changes that are required, but philanthropy and other interested parties cannot simply sit on the sidelines and hope for the best. By joining Board Now, ClimateWorks is making sure that it is proactively addressing its own climate impacts and is helping to make the aviation industry part of the climate solution, not a major part of the problem.

Throughout history, humanity has turned to cooling solutions that work in concert with nature. Returning to these roots would not only be good for the environment – it can also help to beautify our urban sprawl.

As millions of people once again struggle with heat waves in cities around the world, there are lots of lessons we can learn from history about keeping cool. The Roman city-state featured ‘frigidariums’ – large cold pools for people to cool off in. The Egyptians hung reeds across their doorways and windows to cool the wind as it blew in. And the ancient ‘ziggurats’ (essentially roof gardens) of Mesopotamia provided cool, shady places for visitors to escape the blazing Babylonian sun. These and other cooling solutions throughout history make space for nature, working with rather than against our beautiful planet.

Fast forward to 2019 and in our haste to accommodate 3 million more people per week in cities around the world, we seem to have forgotten much of what these ancient civilizations taught us about cooling. Modern city skylines are dominated by steel, glass, and cement, whilst ‘shanty’ towns are typically covered in corrugated iron roofs – materials that act like giant radiators. The ubiquity of air conditioners is noticeable inside and outside of buildings – pumping cold air in and warm air out, in the process heating up local environments.

In our haste to accommodate 3 million more people per week in cities around the world, we seem to have forgotten much of what these ancient civilizations taught us about cooling.

These dominant construction materials and cooling technologies are helping to keep some people cool. However, they aren’t accessible to all and come at a high environmental price – the stability of our climate. Experts predict that the humble air conditioner could use up 20-40% of the world’s remaining carbon budget. So whilst modern modes of cooling provide instant thermal comfort, ironically these very same modes are warming the planet up. Darwin would not be proud.

Fortunately, not everyone has forgotten how to work with, rather than against, nature as we strive to keep people cool. The city of Medellín in Colombia was recently recognized with a prestigious Ashden Award (supported by the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program), for efforts to create ‘green corridors’ in the midst of its buildings, transport routes, and plazas. The results provide a beacon of hope – in addition to keeping the temperature a more pleasant 2-3°C lower than normal, the corridors have engaged communities, beautified the otherwise dull concrete sprawl, reduced air pollution, and enhanced biodiversity.

In Singapore, the government embarked on an ambitious ‘garden city’ plan in 1967 with intensive tree-planting and the creation of new parks. As the population grew and buildings got taller, the focus shifted to include skyrise greenery encompassing ‘skygardens,’ vertical planting, and green roofs. More recently, the government introduced the LUSH policy – Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises. LUSH requires new buildings to offset any loss of nature with new areas of greenery, including on walls and roofs. Parts of the city literally look like the hanging gardens of Babylon and bring with them 2-3°C temperature reductions and the multiple benefits of cooling by nature.

Italy’s ‘Bosco Verticale’ (Vertical Forest) is a pair of residential towers in the Porta Nuova district of Milan. The buildings (365 feet and 260 feet tall) are adorned with some 780 planted trees and countless numbers of plants, altogether integrating about 1,000 different species into the property. Each apartment has its own private garden, which not only looks great, but also filters sunlight to keep temperatures down and cuts down on noise and air pollution. The gardens are watered through a self-replenishing irrigation process and photovoltaic panels on the roof that convert sunlight to electricity.

Despite these success stories, very few governments around the world, at the national or city level, have seized the opportunity for cooling by nature. Significantly more can be achieved to regulate urban heat islands and rising global temperatures by making space for nature in cities. The September Climate Summit in New York presents a key near-term opportunity for countries to commit to more natural cooling in their national cooling plans. This does not, however, mean jettisoning modern cooling, although air conditioning systems need a paradigm shift in energy efficiency and to move away from super-polluting fluorinated gases that can stay in the atmosphere and contribute to climate change for centuries to come. The future of cooling should blend old and new – mixed modes that first aim to minimize heat (for example by making space for nature), and then address residual heat with locally and culturally appropriate, climate-friendly technologies, such as super-efficient air conditioners using natural refrigerants, or by using renewably powered fans.

Aldous Huxley once said, “That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history.” The stability of our climate demands better. We need a renaissance in how we cool our cities by taking lessons from the past and making space for nature. And as with renaissance art, citizens just might marvel at the beauty that can be created in the midst of our urban sprawl.

A version of this blog was given as a speech at the Inaugural U.S. Green Bank Summit on July 11, 2019.

Public activism has supercharged the federal climate policy discussion and pushed the issue high on the political agenda. Politicians have been clamoring to offer their version of ambitious climate policy action since Democrats Senator Ed Markey and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, introduced their Green New Deal resolution back in February for a massive 12-year public mobilization to decarbonize the U.S. economy, and House Republican Matt Gaetz offered his Green Real Deal paean to American innovation in response.

Calls for a federal “climate investment bank” or “green bank”—a public financing authority capable of using its balance sheet to mobilize private investment in the low-carbon economy-have started to become a cornerstone policy position, with calls for one in Congress and by Presidential contenders Inslee, Bennet, and O’Rourke. Last week, Senators Markey and Van Hollen put forward the most detailed proposal yet, introducing the National Climate Bank Act of 2019.

Interest in the model is not limited to the U.S., with green banks or similar entities operating in Australia, the UK, Malaysia, and Japan. One is being established in New Zealand and South Africa, one is proposed for the EU by the European Commission’s new president, and a raft of other governments are exploring the model.

ClimateWorks Foundation has had a long-time interest in green investment banks under our initiative Entrepreneurial Public Investment for Climate (EPIC). Through EPIC, we’ve developed a philanthropic strategy to expand the model both here in the U.S.—at the federal, state and municipal level—and in other industrialized and emerging economies around the globe. We collaborate closely with allies like the Energy Foundation, Coalition for Green Capital, Natural Resource Defense Council, Rocky Mountain Institute, Vivid Economics, and E3G, and of course the Green Banks themselves, supporting networks like the American Green Bank Consortium and global Green Bank Network and their individual members.

Whether you believe that U.S. climate policy is achieved through innovation policy or New Deal-style public mobilization, a national green bank is a crucial policy tool whose moment in the U.S. has arrived.

On the one hand, green investment banks offer a very important tool for innovation policy. Traditionally, the policy script on innovation has emphasized that we need more publicly funded research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) avenues to help create a prosperous low-carbon economy. I am all for doubling our RD&D budget for new clean energy technologies and zero-carbon industrial processes. But any serious innovation expert will remind you that the innovation is not typically a linear process that begins at R&D and ends at commercialization—serious policies support technological change through the commercialization and deployment stages where early investment and supportive policies drive technologies down the cost curve, as with solar PV and now battery electric buses. For that, we need tools to help introduce investors and lenders to technologically proven innovations faster. Well-designed, green investment banks have the mandate and design to take innovations with demonstrated commercial potential, and accelerate their adoption through a broad range of financing tools.

An argument can be made challenging the role of public capital in accelerating market formation. You might say “credible innovations will find financing on its own.” The problem with this argument is that commercial banks are slow to enter new markets and with climate change, timing is everything. The first green investment bank was launched in the UK (by a conservative government), and was able to open the secondary market for offshore wind through its first-of-kind offshore wind fund, quickly attracting commercial capital to the sector, and driving down deployment costs. In a matter of years rather than decades, offshore wind has become one of the most affordable energy generation technologies in the UK. Green investment banks are the missing piece to an “innovation” focused climate policy. To use an American football analogy: if RD&D gets technologies to “third-and-one,” green banks get those technologies over the first-down line toward the goal of commercially financed deployment at scale.

You might also ask, why the need for a green bank since we have had federal programs where we’ve used financial tools to accelerate commercialization of low carbon innovations, like the creation of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program and Advanced Research Projects Energy Financial Assistance Program (ARPA-E). I think these programs have been great. The Loan Guarantee Program helped transform the solar, storage, and automotive industries at considerable public savings, and even generate a profit by bearing commercialization risk that the market was hesitant to adopt.

In fact, my own interest in green investment banks dates back to my law practice in energy and infrastructure advising on the U.S. Loan Guarantee Program, and transactions involving institutions like the U.S. Ex-Im Bank and Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). It impressed upon me that institutions like OPIC bring a commercial rigor that could benefit economic transformation here at home, as is the case with Germany’s KfW. I also saw that it was harder to get commercialization financing up and running through a stand-alone program at the Department of Energy, as was the case with the Loan Guarantee Program. There is administrative value in consolidating financing authority in a single institution. A green investment bank can be equipped with a broad set of financing tools rather than just, say, loan guarantees or debt financing (they can also educate the market about new opportunities, and provide feedback to policy-makers about market development to make for better policy). Commercially minded bureaucrats are hard to come by, and we should wring as much public benefit out of them as possible.

I also want to highlight the “progressive” case for green banks. We do need a much bolder public sector response given the size of the challenge. According to a recent report by the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, we need an 80% reduction in greenhouse gases from 2005 levels to achieve net neutral emissions in the U.S. economy by mid-century, while emissions have grown considerably since that time. Anyone hawking the same public policies of a decade or two ago for climate crisis now simply does not know the science. In a political moment where public finance mobilization under a “Green New Deal” is remarkably politically popular—more so than even fiscally conservative tools like a carbon tax—green investment banks provide a way to put public dollars to work efficiently and effectively by using them for financing and crowding in the private sector for scale. This also sees the potential for “mission-oriented” public sector leadership in forming new markets, not merely a role in following and fixing them. In healthy, effective public-private relationships, public institutions can identify major challenges like decarbonization, and use their fiscal capacity and ability to bear risk to foster market development in those challenging areas. The National Climate Bank Act would even empower the climate bank to finance the closure of existing fossil assets, which now appears necessary to meet climate targets.

Given the scale of the climate crisis, we need a bigger commitment, and we need every dollar to go further. By providing near-market terms, green banks get more out of every public dollar committed, and also provide a more relevant demonstration effect for commercial financial institutions. Green investment banks can drive credit growth in markets that can make financing more inclusive—supporting renewable energy and energy efficiency products for lower and middle-income housing, for example, as Connecticut Green Bank has done. They are a fiscally responsible mechanism for Green New Deal-style public mobilization.

We at ClimateWorks Foundation will continue to support efforts to mount a public finance response to the climate crisis that is up to the challenge, spurring markets for low-carbon innovations and doing so in a fiscally responsible manner. We are eager to see the day that the U.S. establishes a federal green bank.

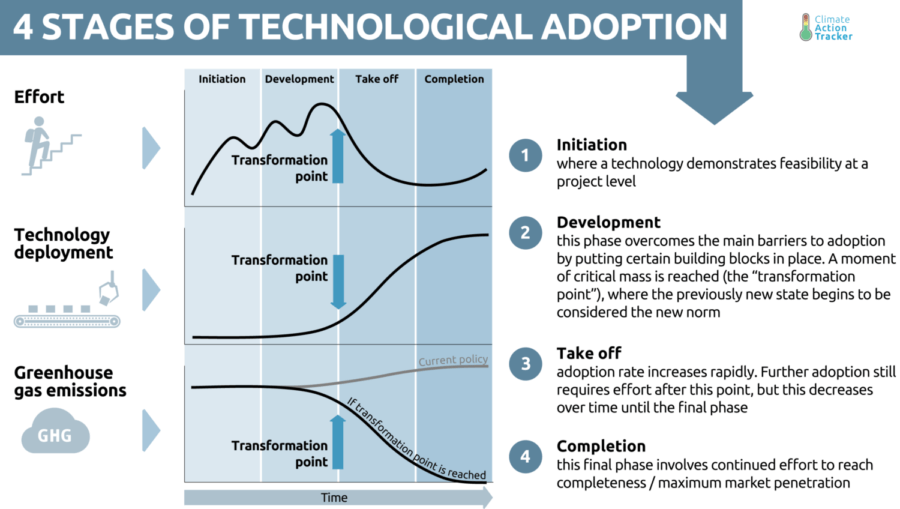

Transformation points for clean energy solutions can put us on the path to 2050 today.

This strategy brief is part of a series on 2050 Today: A ClimateWorks initiative that is mapping out research and strategies to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century.

Download Today

[ninja_form id=12]

Infrastructure being built and planned today will determine whether or not the world meets its 2050 goals to keep temperatures well below 2 degrees Celsius. In other words, the actions we take today to transition to zero-carbon technologies—such as wind, solar, electric-drive vehicles, etc.— will set the pace for whether clean energy will outcompete fossil fuels in the future.

Fortunately, several of the key technology and policy solutions to address climate change are already near the point of rapid market adoption (e.g. wind, solar), or are within sight (e.g. electric-drive vehicles, zero-carbon buildings).

In this new strategy brief you will see:

- A review of the key conditions that define a transformation point for climate solutions.

- Five ‘accelerators’ philanthropy can pursue to achieve transformation points.

- An overview of how the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner, safer energy technologies is happening much faster than previously predicted.

- Examples of how ClimateWorks Foundation and its partners are integrating transformation points into strategies to tip the scales on electric-drive vehicles and to accelerate sustainable finance to reach transformation points.

- Recommendations for those interested in pursuing transformation points for climate action.

Download the strategy brief using the form above.

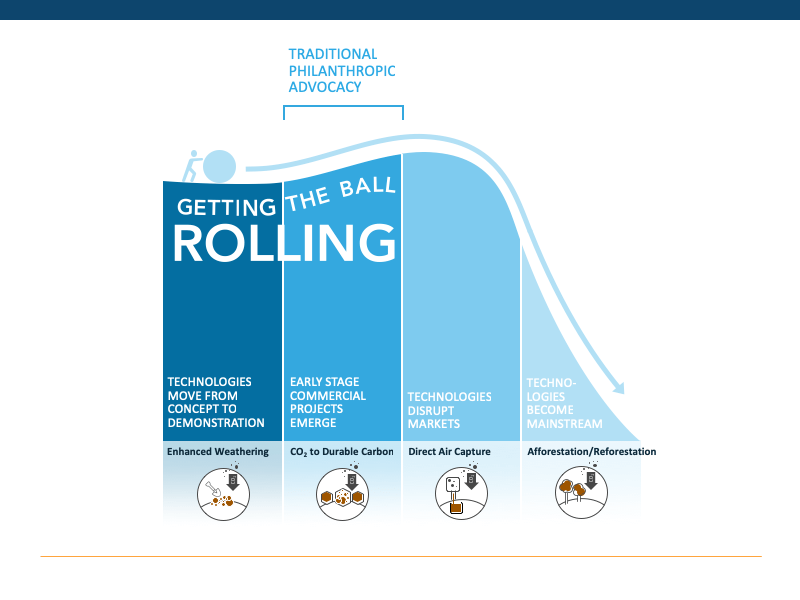

Climate philanthropy is in a unique position to accelerate progress on carbon removal and increase the odds that multiple removal approaches reach gigaton scale before 2050.

With the landmark publication of the IPCC’s Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5° C, the science is in and the conclusions are clear: by 2050, both the rapid and deep decarbonization of the global economy and the large-scale deployment of carbon removal approaches are imperative for meeting climate goals. And while emissions reductions have long been front and center of the climate conversation, last year saw a shift in the conversation that aimed to add substance to the second half of the climate equation. A plethora of reports (The National Academy of Sciences, New Carbon Economy Innovation Plan, and the Royal Society Report to name a few) put pen to paper on the critical need for and “state of” many of the leading carbon removal solutions. With enough information in hand, we are now well equipped to move past debating ‘why carbon removal’ to ask ‘how can we achieve carbon removal at scale before midcentury?’ Thus, it is of critical importance to take stock of what we know (and don’t) about carbon removal solutions, and to develop an associated philanthropic strategy that will make it possible to realize the full potential and scale of these solutions, while taking into account their varying levels of technological readiness.

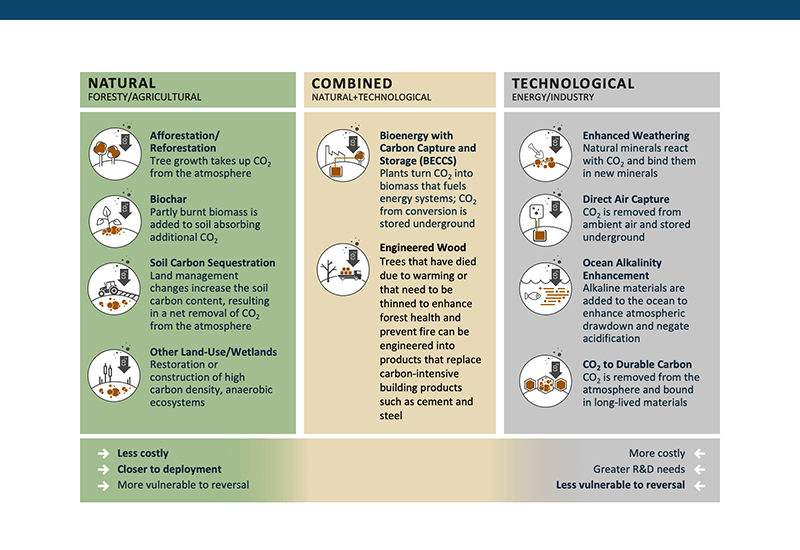

What is Carbon Removal at Scale, and How Can We Achieve It?

Scientists estimate that carbon will need to be removed at the scale of over 10 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2050 — an amount that roughly equates to a quarter of total global annual emissions today. In order to reach such a monumental scale by midcentury, work needs to begin today on researching and deploying a portfolio of carbon removal solutions, with an interim goal of removing 6 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2030. Constituting less than two percent of all philanthropy, we don’t imagine climate grants alone will get us to scale but we can help create better rules and tools to attract the patient capital and private investment needed to get the job done.

And while this task is daunting, philanthropies have decades of experience engaging with governments, the private sector, and nonprofits in support of innovation and the deployment of new climate solutions; solar is a notable example. Today, each carbon dioxide removal approach sits on the innovation curve at different levels of technological readiness. Many solutions, like direct air capture (DAC), forestry, and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) are ready for traditional philanthropic support that funds policy development, advocacy, and communications.

Other solutions, however, still need significant investments in fundamental research, evaluation of challenges and opportunities, and early demonstrations. Some foundations fund such early-stage solutions in the realm of peer-reviewed scientific papers, but others fund advocates to champion new policies to help scale solutions. Because it is too early to know which solutions will prove to be the most scalable or economical, it will be essential to exercise humility in acknowledging that we don’t know which approaches will play the largest role in climate mitigation until these techniques are proven in real-world implementations. The urgency and scale of the climate crisis necessitate that we leave no option unexamined, no stone unturned.

Getting More Solutions Ready for Scale

Moving outside of our funding comfort zone will be critical to reaching scale with a portfolio of carbon removal solutions. Not only do we need to get the ball rolling by creating an enabling environment for mature solutions, but we need to do technology and policy assessment for early-stage options to understand their ability to contribute to negative emissions at scale.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that more mature solutions merit less support—rather, forestry, BECCS, and DAC simply require different types of support concomitant with their relative level of technological readiness. For instance, funding for communications is required to socialize the understanding that not all removal equates to BECCS, and that direct air capture is poised for rapid cost reductions as it will benefit from learning by doing and economies of scale (much in the same way as solar photovoltaics continually beat expert forecasts on price declines and capacity additions). However, we will focus this discussion on several less-heralded carbon removal solutions: enhanced weathering, soil carbon sequestration, and ocean removal approaches. Many of these solutions still have major question marks that philanthropic funding can help answer in order to drive their development forward.

Enhanced weathering: Over geologic time scales, the natural weathering of rocks containing certain minerals — like serpentine, silicates, carbonates, and oxides — draws down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and stores it in stable mineral forms, thereby playing an important role in regulating atmospheric CO2 concentrations. The centuries and millennia that these reactions typically take are too slow to help with the climate crisis. Fortunately, there are ways of safely speeding up the weathering. By grinding up rocks to increase their reactive surface area or by adding heat or acids to speed up reaction rates, enhanced weathering could be an important climate solution with huge potential to scale. (Experts estimate that, after considering energy requirements, enhanced weathering could reasonably remove up to 4 gigatons of carbon per year.) Philanthropy can support basic research to substantiate these claims in the real world, focusing on supporting process improvements and mapping resource potentials. If the benefits of enhanced weathering prove to exceed the challenges, the near-term research efforts funded by philanthropy can help unlock greater government RD&D and help secure private capital to move this approach from the lab to pilots.

Soil carbon sequestration: Soils have the potential to store carbon at scale, though global soils have historically lost an estimated 133 Gt of carbon due to human-driven land use change. Today, there are a wide variety of land management strategies, practices, and technologies that fall under the aegis of soil carbon sequestration that can restore a portion of this lost carbon. However, there is no one-size fits all system that can help realize that scale. The efficacy of these practices turns on local soil type, climatic factors, and crop type. Philanthropy has been and should continue to fund research to better answer basic questions around which practices are most effective in what scenarios and how permanent the removal is. In addition to practice change, research to explore new varieties and crop types that sequester more carbon will be critical. For example, we are learning that switching to crop types with long roots, such as kernza, may support even greater soil carbon storage potential than can be realized through land management practice changes alone.

There is also currently no streamlined, consistent, and cost-effective way to measure and verify soil carbon sequestration on the farm-level. This lack of protocols could greatly influence our assessment of soil carbon sequestration potential and hinder the incorporation of these practices into climate policy frameworks. Philanthropy can play a big role in incentivizing streamlining among current standards and in helping to set up the frameworks of the future.

Sequestration efforts should also be combined with efforts to boost crop yields, allowing us to both store more carbon in the soil, prepare our food systems for the effects of a changing climate, and free up additional land for high-carbon ecosystems (such as forests and wetlands). Increasingly, land will be stretched to deliver on multiple priorities — from food production to ecosystem services to bioenergy production to carbon sequestration — and philanthropy can play an important coordination and consolidation role among these veins of research.

Ocean approaches: There are a number of ocean-based approaches that haven’t been explored in detail to-date. In fact, the National Academy of Sciences excluded ocean approaches (except coastal wetland restoration) in their recent landmark report. These approaches utilize ocean ecosystems to sequester carbon and can include direct ocean capture, kelp farming, ocean alkalinity enhancement, and other blue carbon approaches. Because many of these strategies are in the early stages of development today, it will be important for philanthropy to support analyses to better understand the technical and economic potential for these solutions, as well as any risks from early deployment that would necessitate governance standards in the near term.

Climate philanthropy is in a unique position to accelerate progress on carbon removal and increase the odds that multiple removal approaches reach gigaton scale before 2050. Our theory of change is rooted in our abilities and limitations. Philanthropy can support research (both into technical aspects and communications and messaging strategies), fund advocacy, policy development, and governance frameworks, and take on risks that governments or the private sector can’t or won’t. However, philanthropic resources are small relative to the many trillions in public and private capital that will ultimately need to be allocated toward climate solutions. Thus, any credible strategy from philanthropy should be focused on removing barriers and unlocking other forms of capital.

The task ahead is daunting, and we are clear-eyed about what Paris-compatibility will entail – multiple simultaneous transformations in the ways that we produce, transport, and consume. Carbon removal is not a stand-alone task, but must be integrated into the larger economic and ecological systems they are deployed into. There are some carbon removal approaches that we know will have multiple benefits and can scale — these we should begin supporting through communications, policy development, advocacy, and investment. There are also many other approaches where it is too early to tell if they will be able to contribute to large-scale removal — but the urgency of the problem demands that we explore all options that hold the promise of arresting and reversing the climate crisis.

For further reading: Our 2018 blog post, ‘Carbon Dioxide Removal is a Necessary Complement to Deep Decarbonization’, makes the case for including carbon removal as an integral component of the global response to the climate crisis.