Covid-19 has prompted serious soul-searching and examination of daily travel patterns and behavioral habits across many consumption-driven societies — how many of those car trips and flights were actually necessary to begin with? Travel activity around the world all but ceased during some periods, emissions dropped but are starting to rebound, and the question remains: Will recovery bring us back to where we started, or will we seize the moment to keep emissions low for the long term? As laid out in our previous blog on Covid-19’s impact on the climate, sustained reductions in activity levels are unrealistic and will be insufficient for reaching international climate targets. While it may take time for air travel and marine shipping to return to previous levels, the movement of goods and people will rebound along with greenhouse gas emissions, in the absence of incentives to shift to clean technology.

The clear skies and empty streets during shelter-in-place didn’t change the strategic calculus of transportation decarbonization — it only reinforced the need to electrify vehicles and shift to less energy-intensive modes of transportation. With this in mind, we worked alongside partners from the Grantham Institute and PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency to examine how reward schemes could incentivize low-carbon travel and/or mode-shift to more sustainable transport options. The report, “Incentivizing low-carbon travel: Lessons from a wide range of reward and platform schemes,” offers a first look into how reward schemes can be used as levers for climate change mitigation.

Lessons from private and public transportation rewards schemes

In the course of our inquiry, we arrived at three primary lessons:

1. Reward and platform-based schemes related to some aspect of travel are globally ubiquitous across commercial and public domains. Incentives can vary greatly based on the modes of travel they target and the mechanisms they use, and any of those can warrant its own deeper research. Examples include anything from private sector schemes such as airline mileage programs and gas station loyalty programs, which tend to incentivize high-carbon travel, to public sector schemes such as low-emissions zones and bike-sharing systems, which provide access to low-carbon travel or incentivize low-carbon travel by penalizing high-carbon options. Private sector schemes tend to be more commonplace and diverse, which makes it difficult to develop a systemic way of disrupting the high-carbon travel they incentivize, but they also provide an enormous opportunity to drive reach and impact, if restructuring is done right.

2. There are clear distinctions between schemes designed to promote or support low-carbon travel (e.g., bike-share systems) and those that incentivize high-carbon travel (e.g., airline rewards) that in turn have adverse effects on the climate and air pollution. Among a wide-ranging selection of schemes that reward or support low-carbon travel that we examined, all require three components to work:

- An aspect of data-sharing enabled by data regulations and public-private partnerships;

- Availability of public infrastructure that supports a shift toward sustainable travel options; and

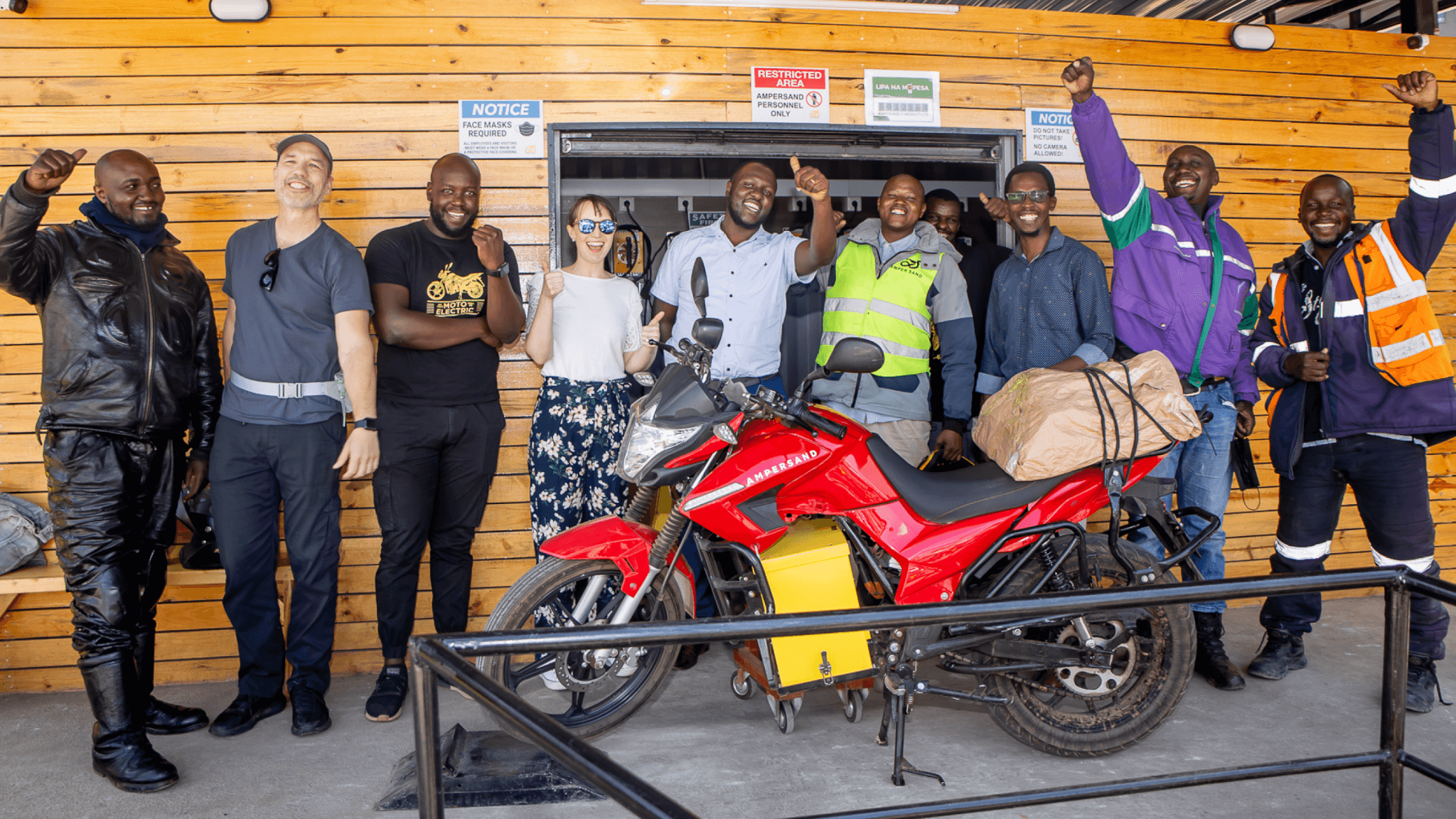

- Market supply of zero-emissions travel modes for private or shared use (e.g., bikes, e-bikes, e-scooters, electric mopeds, electric vehicles, and others).

In comparison, schemes that result in or incentivize high-carbon travel usually promote increased volume and frequency of consumption (e.g., the more money a person spends using a credit card with a reward system, the higher the resulting rewards, leading to ever greater incentive to keep consuming). Overwhelmingly, these have two key levers in common:

- They focus on maintaining and reinforcing spending and consumption behaviors, among which high-carbon travel is an option.

- They require membership and are integrated with a specific platform that offers rewards, such as air miles programs and credit card reward programs.

3. Given the multi-tier complexity and the private sector ownership of current schemes, any effort to redirect spending toward greater climate benefits will require government intervention and multi-stakeholder partnerships. Government action is required to effectively curb the self-perpetuating cycle of air travel through possible interventions such as a tax on air miles (proposed in U.K. government), as airlines have little incentive to curtail these profitable practices on their own. Partnerships are crucial for schemes such as the Miles App, which relies on a network of corporate partnerships to offer low-carbon travel rewards for accumulated points.

Philanthropy’s role in elevating and leveraging reward schemes for climate

Covid-19 has given us an opportunity to re-imagine transportation networks and look beyond the most obvious approaches to reduce travel-related emissions. Using rewards programs as a leverage point is one potential pathway toward a different future. Philanthropy can help close the gap between government and private sector incentives for low-carbon travel by supporting several initiatives:

- Research on regulatory actions that can restructure high-carbon rewards programs to account for climate outcomes;

- Support for low-carbon travel reward pilot programs such as ClimatePerks, and widespread replication and scaling; and

- Convening key stakeholders to rethink public-private partnership structures shaping behavior shifts toward lower-carbon travel.

Reversing the vicious cycle in which consumption enables and incentivizes high-carbon travel isn’t a climate solution by itself, just as clean technologies cannot begin to reverse climate trends in the absence of strong supporting policies. Zero-emission technologies may be an important way to transition away from fossil fuels, but incentivizing their use in order to meet international climate goals will require deep recalibration across every segment of society, close inspection of every mechanism that keeps fossil-based transportation in demand, and understanding of how to channel that demand toward low-carbon travel.

To reach our climate goals, we need to start making big progress in these three key industries.

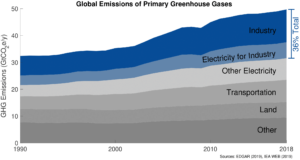

Industrial production is responsible for one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions mostly come from production of a small number of very emissions-intensive materials like steel, cement, and basic chemicals. In order to reach our climate goals, we need to start making big progress in these industries.

Industrial production is responsible for one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions mostly come from production of a small number of very emissions-intensive materials like steel, cement, and basic chemicals. In order to reach our climate goals, we need to start making big progress in these industries.

Unfortunately, low greenhouse gas alternatives to these basic materials are not widely available. There are lots of reasons for this, but mostly they boil down to no incentives to produce clean materials. The best way to create those incentives is to create a market so producers of low-emissions materials can be paid a premium price.

There are four reasons why creating markets for such materials will be effective:

- We need to justify major additional expenditure. All of the ways to make meaningful reductions in emissions will require capital improvements to existing factories, new factories, increases in operating costs, or a combination of these. Industrial capital is expensive—even modest upgrades can cost tens of millions of dollars. Manufacturers will want to be sure their investment in low-emissions process upgrades will yield higher revenues than business as usual. Market demand will justify new, cleaner production processes so firms can be sure there will be customers ready to buy their low-emissions materials.

- Dirty products won’t be able to undercut clean products. We could use regulation to require factories to invest in clean production, but steel, cement, and chemical products are traded all over the world. If we’re not careful, dirty materials produced outside the reach of the regulations could undercut the clean materials on price, and the manufacturers who invested in clean production would lose business. This problem goes away if we focus on building demand for the final products: the cars made with clean steel or the infrastructure made of clean concrete. The rule would be that in order to sell in this market, the materials need to comply with an emissions standard, no matter where they were made.

- The rules will be enforceable. Creating markets also lets you focus on the materials that have the biggest climate impact and that don’t create huge compliance problems. Instead of having to figure out the supply-chain emissions of every single product that is being sold in the economy, regulators will just have to verify the documented supply-chain emissions of the specific products that are seeking access to the market.

- The final consumers will hardly notice the costs. The cost of raw materials like steel, cement, and basic chemicals make up a very small portion of the cost of finished goods. For instance, structural materials like steel and cement are typically only a few percent of the price of a building. Even in a very steel-intensive product like a car, the steel is only about 3% of the price. The ethylene in the plastic is much less than 1% of the price of a bottle of water. Most of the cost of these products is in the labor of transforming materials into finished goods. So even early-on, when potentially higher-cost, low-emissions production processes are coming online, there will be almost no impact on the cost of the final products. By creating market demand for products made of low-emissions materials, we ensure that the costs of reducing emissions are paid by the final consumers, who can most easily afford it.

There are lots of ways to create a market, and different ones will be appropriate in different contexts. For example, we could:

- Require that all building materials that go into roads and other public construction projects must be low-emissions.

- Create voluntary certifications that allow consumers to choose low-emissions products.

- Regulate the supply-chain emissions of specific products, like cars or appliances.

- Enact subsidies to make up the difference in price between low-emissions and high-emissions materials.

- Use codes, standards, and specifications that have preferences for low-emissions materials.

The right option will depend on the particular product and the particular circumstances, but we need to get started now. All of the other things we need for a climate-safe industrial sector—technology development, financing and investment, massive retooling—won’t happen unless we create places and structures where manufacturers can profit by selling clean materials.

Civil society is already working to accelerate the transition to climate-safe industry and manufacturing. Grantees and allies of ClimateWorks are already working on many of the approaches listed above, and have already seen important progress. For example, education and outreach activities from groups like the Sierra Club and the BlueGreen Alliance was critical to passing California’s first-in-the-nation Buy Clean law, which requires certain building materials in public projects have lower greenhouse gas emissions. ResponsibleSteel is creating the first multi-stakeholder voluntary certification for responsibly-produced steel. We are now working to scale up these activities in partnership with our network of aligned foundations and NGOs.

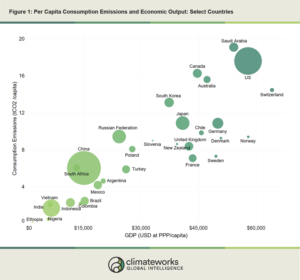

As the world grapples with the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the international trade system is being buffeted by demand shocks, trade restrictions, and supply chain disruptions. The global pandemic will have profound and lasting effects on global trade, many of which are impossible to predict. Among early developments, we see a wave of countries and regions, including China, EU, U.S., and Japan, reverting back to protectionist policies for medical equipment and other products, and the prognosis for how the current situation impacts the clean energy transition remains speculative for now. As the world slowly recalibrates its trade policy and industry recalibrates its supply chains, philanthropy must remain watchful for windows of opportunity to shape these changes and drive positive outcomes for the climate. Drawing on our contribution, “Trading Blame or Exporting Ambition?,” to the recent Overseas Development Institute publication titled “Counting Carbon in Global Trade,” we highlight here why trade matters for the climate, how its impact on emissions can be tracked, and what philanthropy can and should do in response.

Why trade matters for climate: Friend and foe

Trade is a tool that can be leveraged for climate action, but the current reality is decidedly more mixed. Trade enables economic activity that contributes to rising greenhouse gas emissions, and the sheer volume of traded goods and services, as well as the varied policy regimes they are subject to, offer both the potential for clean procurement and a liability for carbon leakage, in which the production of carbon-intensive goods shifts to jurisdictions with lax environmental standards. In some cases, national laws put a higher price on emissions produced in-country, leading to carbon leakage by driving substitution toward imported goods or services that can be provided more cheaply without adherence to these standards.

Following trade emissions

How can philanthropy help

Philanthropic resources deployed for the public good have the power to catalyze action and accelerate climate solutions. Given the global reach of international trade, there is a need to assess how and where to advocate for policies that help realize trade’s potential for driving decarbonization.

It is unclear the extent to which Covid-19 will reshape the world and economies in the next few years, especially in relation to trade. As part of the economic recovery process, we expect to see increased infrastructure investments as part of many fiscal stimulus plans that are being enacted around the world, as well as the need to shorten and nationalize supply chains. These can have a large impact on consumption, tariffs, trade barriers, labor markets, trade flows and agreements, new alliances in response to protectionism, and other outcomes. There are many such trends to watch for, as well as new opportunities to influence low-carbon investments. We list a few examples in Table 1.

The way forward

The global trade system is at an inflection point, buffeted by the U.S.-China trade war and the physical and economic shock of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is an opportune moment to step back and reflect on what outcomes the current system is driving, and to reimagine how trade can be put to work for climate change mitigation. Public procurement and environmental standards, climate clubs, and border carbon adjustments are all different means to the same end — to stimulate green investments, prevent carbon leakage, and to harness the skills and resources of the global community to tackle this pressing global challenge.

Diplomatic engagement and outreach have become defining features of India’s response to the Covid-19 crisis. In addition to providing medical aid and supplies to over 120 partners near and far, New Delhi has been active in multiple bilateral and multilateral forums, indicating a strategy that looks beyond the current pandemic, with humanitarian assistance and disaster relief at the epicenter. As many parts of the world are bracing for the double effects of Covid-19 and climate-induced extreme weather events — India itself is dealing with the aftermath of Cyclone Amphan — New Delhi’s two-pronged approach may be a ready toolkit to ameliorate the impact.

India’s template to place climate-related diplomatic and humanitarian relief efforts at the center of its geopolitical ambit already exists. The country’s two signature multilateral initiatives under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), are the first to be headquartered in India and embody both of these elements. With sustained focus, they could become key mechanisms to mobilize finance for developing countries and enable capacity-building and greater energy access in a sustainable way.

ISA, conceptualized as a platform for catalyzing cheap clean energy transitions and technology transfers among the countries that lie between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, was opened up for membership to all U.N. member countries in 2018. Following this internationalization, ISA now has 67 members including key Indian neighbors like Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka, as well as the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and over 30 countries from Africa.

CDRI was launched in September 2019 as an international partnership aimed at mitigating the impact of extreme climate events and other disasters by developing resilience in ecological, social, and economic infrastructure through knowledge transfers, technical support, and capacity-building. With support from the U.N. Office of Disaster Relief Reduction, World Bank, Green Climate Fund, and its 12 founding members including Japan, Australia, and the U.K., CDRI is poised to expand partnerships with U.N. agencies, multilateral banks, and the private sector.

By focusing on climate diplomacy, energy access, resilience, and disaster relief, especially in developing countries, ISA and CDRI can be instrumental in bridging key gaps in global climate action. One such challenge is that collective climate action has lost momentum in the recent years, especially among the highest-emitting nations. In addition to the U.S. retreating from the Paris Agreement, the 2019 U.N. Conference of Parties meeting (COP25) showed that key emitters will continue to put individual interests ahead of collective action, with primarily small island nations pushing for enhanced climate ambitions and bigger, bolder action.

India, too, did not have a breakthrough at COP25, but has made some major strides in renewable energy growth and, according to some pre-Covid-19 estimates, is on track to meet its emissions targets under the Paris Agreement. While there is certainly space to embolden its ambition, and not lose momentum in post-pandemic economic recovery, India’s recent diplomatic engagement could signal that the country’s leadership is moving toward adopting a collaborative approach driven by India-led climate diplomacy.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, India has joined an International Energy Agency-led meeting of global energy ministers to discuss the role of clean energy economic recovery planning; regularly engaged with the Quad Plus (the U.S., South Korea, Vietnam, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand) to pool resources and coordinate responses; and joined the Alliance for Multilateralism meeting to declare support for the World Health Organization, the U.N., and other international and regional organizations. India has thus shown significant willingness to lead and join small, targeted coalitions and charted the course for ISA and CDRI to serve as springboards for rallying collaborative climate action.

Promoting alliances and partnerships based on renewable energy technologies could, therefore, shape the contours of India’s climate leadership. It is reported that the Indian government is taking steps to roll out the ambitious One Sun One World One Grid project aimed at global grid interconnections to share solar and other renewable energy through a phased approach starting with India, the Middle East, and South and South East Asia, followed by Africa and the rest of the world. This announcement comes just days after a reported boost to the potential establishment of a World Solar Bank under ISA, which could expedite solar projects in member countries and cement ISA’s significance as an instrument for mobilizing finance. Moreover, the fact that Prime Minister Modi highlighted ISA and CDRI at the recent Non-Aligned Movement summit suggests that these two India-led initiatives will likely receive a larger role in the country’s strategic calculus.

India’s efforts to enable affordable and clean energy transitions is timely because the Covid-19 pandemic has thrown a spotlight on the intersections between climate and public health. Renewable energy technologies can play a critical role in expanding energy access, powering medical facilities, and facilitating greater access to healthcare. Past innovations like “solar suitcases” — first deployed in Nigeria to counter high maternal mortality and since then supplied to 27 countries — and solar-powered boat clinics in Assam demonstrate the potential of renewables to save lives, build resilience, and reduce carbon emissions. Initiatives like ISA, with an overarching goal of mobilizing $1 trillion by 2030, can not only facilitate greater innovations but also be the key platform for their deployment and transfer to countries most lacking in access to energy.

Covid-19 has tested the resilience of existing health, energy, and transport infrastructures and compelled a re-imagining of social norms and economic contracts. Building advanced, sustainable, and resilient infrastructure that can adequately respond to disasters like Covid-19 and those brought on by climate is not only urgent, but requires innovative, immediate, and immense global effort. India’s climate diplomacy channeled through CDRI, ISA, and other such means could prove to be important cogs in giving momentum to this giant wheel.

We all knew it was coming.

We knew that while a pandemic was unlikely to materialize at any specific point in time, it was highly likely — in fact certain — to emerge at some point.

According to the World Economic Forum, the threat of infectious diseases has been a top 10 global risk for years. That moment has arrived, revealing just how unprepared we were for the inevitable.

Behavioural economists have come up with fancy words to explain why: cognitive dissonance, hyperbolic discount functions, normalcy bias. These terms all try to capture the sad reality that we knew a crisis would come, yet did little to prepare. Ultimately the Covid-19 crisis shows us that Investors, companies, and governments need to do more to anticipate tail and mega risks and create actionable strategies to prepare for them.

While attention now is rightfully on the now-crystalized risks of Covid-19, climate-related risks continue to mount, and there is much to learn from current events on how to manage them.

As to the actual nature of Covid-19 compared to climate risk, there are obviously some differences to acknowledge upfront. Unlike a pandemic, the physical risks of climate change, inevitable in all but degree, will be more of a mix of gradual and sudden impacts. Gradual physical impacts will look like shifting crop production, water scarcity, and potentially climate-driven migration. The sudden impacts like droughts, crop failure, storms, and heatwaves — especially in combination — could generate shocks similar to Covid-19, but most likely on the localised level of individual economies or regions, rather than on a global scale.

But there are also some crucial similarities. Covid-19’s economic and financial impacts come from both the severity of the disease and the forceful societal response that it requires. Climate change’s “transition risks” of regulatory and techno-economic change are often modelled as gradual changes precisely because it is the least financially and economically disruptive path. But there is good reason to believe that the shape of the policy response to climate change will have more in common with a pandemic “lockdown” than is immediately apparent. The speed and severity of policy change may be different, but have no doubt that policymakers will act forcefully in a crisis.

The Principles for Responsible Investing (the PRI) commissioned the Inevitable Policy Response, a policy forecast to help investors anticipate and navigate transition risk, which projects that we are increasingly likely to face a bumpy techno-economic and policy ride toward zero greenhouse gas emissions.

As with Covid-19, failure to prepare society for mounting risks simply compounds the severity of the policy change necessary to contain the harm as it manifests. A good pandemic forecast may have foreseen both the health crisis and the fragmented, forceful, and disorderly policy response that has ensued because of inadequate preparation. Anticipating this dynamic is crucial to being able to take preparatory action and avoid reactive policy and worse outcomes.

The challenge to preparing for these types of risks are threefold.

The first challenge is believability. It didn’t seem realistic or reasonable to assume that one-third of the global population would be on lockdown due to a pandemic, with industrialized countries’ hospitals testing their limits, U.S. crude oil prices going negative, and skyrocketing unemployment. Alas, this pandemic and the policy response to it has put much of the believability issue to rest in terms of expecting the “unexpected.” Many of the impacts we see now are from the stringent (and, in our view, entirely prudent) policy response to the pandemic and not from the disease itself. So too with climate change. The hope is that today’s once unthinkable crisis expands our horizon on not only the possibility, but the high probability, of large-scale, climate-driven disruption to society, the economy, and the market.

The second challenge is complexity. Climate change, like pandemics, is a complicated challenge, with complex impacts and feedback loops across the economy and investment portfolios. When people are faced with too much complexity, they often revert back to the familiar. For the pandemic, this may have meant imagining some of Covid-19’s public health impacts, but not foreseeing the broader disruptions to commerce, trade, and human capital that would ensue from reactive emergency management. For climate change, analysts revert to base case expectations of continued emissions growth.

The key counterweight to complexity is inevitability. A future with no pandemics, and no pandemic management policy, isn’t actually a believable future anymore, even if understanding the alternative futures is complex. So too with the impacts of climate change, and the societal and political response to it. Scenario analysis is a useful antidote to complexity, helping us to navigate the inevitable. The Bank of England has been leading a process to map out a range of climate economic scenarios on behalf of a network of over 50 central banks and supervisors. These authorities can then stress test banks, insurers, and pensions, including against an abrupt climate “Minsky moment” of sudden market repricing from climate policy, to ensure that the markets take them into account.

Still, while a range of scenarios are useful, the markets still need a base case. What do we actually think is going to happen? To address this, the PRI has commissioned the Forecast Policy Scenario, a scenario rooted in a high-conviction forecast of the likely delayed, forceful, and disruptive policy change that will ensue as technological, cultural, and climate change spring load the politics of climate policy. This analysis is a critical start to giving the market some needed foresight.

Finally, even if you accept the Inevitable Policy Response, and navigate the complexity, what can you actually do?

As this storm passes, we must prepare for the inevitable transition to a zero-carbon economy. The good news is that there is evidence that investors have begun to batten down the hatches. The Inevitable Policy Response has created a ”forecast policy scenario” and a framework to think about and plan for inevitable transition risks. So, on climate, the roadmap is clearer than one might think. PRI now requires members to undertake and disclose climate-related financial analysis in line with the recommendations of the Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate Related Financial Disclosure. Investors should demand, through coalitions like Climate Action 100+, that the companies they own are resilient to climate risk. Investors can also get ahead of transition risk in their portfolios through pace-setting groups like the United Nations Net Zero Asset Owner’s Alliance. Ultimately investors can work with the PRI, and broader coalitions like the Investor Agenda for climate change, to be the voice that not only calls out the need to prepare for pandemics and the present and future climate, but also does something about it. Society and the market both benefit from rapid and assertive action that anticipates the harm.

An immediate opportunity comes into view. Governments are now on the cusp of initiating rare or even unprecedented fiscal stimulus. We have the opportunity to green that stimulus or shovel money into carbon-intensive sectors and load the economic with further risk. It is a crucial opportunity to minimize the severity of a future carbon lockdown.

This pandemic is a lesson for what happens when we don’t prepare. Let’s make sure climate change isn’t.

This piece was first published in BusinessGreen.

As the world continues to grapple with the unfolding consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, the focus rightly remains on protecting public health and remedying the social and economic ramifications of physical distancing measures. As second order consequences of the pandemic response, transportation activity and the price of oil have cratered, electricity consumption has decreased, and in some corners a heretical thought is being whispered — that the pandemic might, in fact, have a silver lining: reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and by extension a contribution to climate change mitigation.

Some say this out of real concern for the climate; others push it disingenuously, as part of a narrative that environmentalists wish to impose economic hardships en route to achieving their own ends. However, we are finding that emissions reductions attributable to Covid-19 will not appreciably help in arresting the climate crisis, and the current lockdowns bear no resemblance to the just and sustainable future that the environmental community and climate philanthropy are all working toward.

Potential impacts on long-term deep decarbonization

How much can we actually expect emissions to decline in the short run, and what impacts would this have on long-term temperatures? As the economic fallout has become more pronounced, estimates of carbon emissions in 2020 have been repeatedly revised downward, with recent analyses by Carbon Brief and the International Energy Agency (IEA) respectively estimating emissions reductions of about 5.5% and 8%, relative to 2019.

In past recessions, there was a quick return to the emissions trendline, but even if this recession were to persist for several years, overall emissions reductions would have little impact on long-run temperatures if not sustained by stringent climate policies and persistent behavior changes. This is because today’s temporarily reduced emissions are still being added to centuries-worth of greenhouse gases that have accumulated in the atmosphere; unlike local air pollution, the climate crisis only gets worse when the rate of emissions declines but remains above zero. What matters more is our response to the crisis, particularly the trillions of dollars in stimulus spending committed by governments the world over.

Focus on a sustainable recovery

In the best case scenario, a clean energy transition would be the centerpiece of stimulus spending, as the IEA and others have advocated. In the worst case, stimulus packages will amount to a bailout of fossil fuel industries, unless fiscal stimulus packages are closely aligned to a green agenda, which will likely be seen in only a few instances. Either way, ClimateWorks will be tracking the impacts of the pandemic and their implications for climate action by collating climate-related indicators that have been affected by Covid-19 — from transportation activity to green stimulus plans to air quality levels. The table here contains a subset of these indicators, which we will be monitoring as we consider how climate philanthropy can best promote a sustainable recovery.

Emissions intensities are the key

Using the Carbon Transparency Initiative regional models, developed at ClimateWorks, we are able to separate changes in overall activity (such as the amount of oil consumed or steel produced) from changes in the carbon intensity of those activities (the amount of carbon emitted per unit of oil or steel production). In the long run, we find that deep decarbonization relies far more on reductions in intensity than reductions in activity — it is much easier to imagine a modern society built upon carbon-free electricity than one that consumes no electricity at all. Getting emissions to below net-zero (a requirement for stopping and then reversing climate change) means that activity levels cannot get low enough, so long as those activities are continuing to produce emissions. Reducing the emissions intensity of the economy to zero is a necessity in the long run and temporary reductions in activity levels do not change this imperative.

Prospects for a “just recovery”

While there is no shortage of ideas on how to promote a sustainable response to the coronavirus pandemic, adoption of “just recovery” policies by governments around the world has been lackluster so far. Temporary reductions in emissions are real, but instead of being distracted by enforced reductions in activity levels and energy consumption, we should focus on pushing for ambitious policies that drive emissions intensity toward zero, resulting in long-run deep decarbonization. We need to look beyond behavioral changes (such as remote working and virtual conferences) that endure after the Covid-19 pandemic passes and to strengthening proposed and adopted stimulus bills to set ourselves on a pathway toward achieving our international climate goals and the just and sustainable future that we all are striving for.

For more information on how ClimateWorks is responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, see here.

Demand for cooling services will likely rise due to Covid-19. The response needs to be both smart and ambitious.

Over recent weeks, as the world grapples with a global pandemic that is turning our lives upside down, a number of stories have emerged looking at how Covid-19 is affecting air pollution and carbon emissions levels around the world. In many places, there has been a drastic drop-off in emissions, notably from transportation, construction, and heavy industry.

But what about emissions from cooling? After all, cooling for buildings, products, and people uses huge amounts of energy, often inefficiently, and releases fluorinated gases (F-gases) that are far more potent than carbon dioxide in causing climate change. As such, the emissions from cooling alone could offset reductions in other areas and eat up the remainder of allowable global emissions, if we are to meet the international goal of limiting global warming to 1.5° C.

It’s likely that Covid-19 will affect demand for cooling in at least five categories:

1. Cooling in buildings. Billions of people across the world have been asked to stay at home to avoid fueling the spread of the disease. For some, this might be an isolating and inconvenient experience, but nonetheless a comfortable one. For others, however, this could mean being cramped in a small space, with little to no light and ventilation. Temperatures in the Southern Hemisphere and the tropics are already hot enough to require an air conditioner or fan. As the weeks of lockdown turn into months and temperatures rise in the Northern Hemisphere, people will feel the need for cooling. For some, this will not just be about comfort. When fevers are rising, cooling could be a matter of life or death, especially for the elderly and vulnerable. Not only can we expect a surge in demand for the energy and F-gases required for such cooling, but an uptick in demand for air conditioners, central cooling systems, and fans. In today’s uncertain economic climate, many will opt for the cheapest cooling appliance they can get their hands on, which is very rarely efficient or climate-friendly. On the flip-side, demand for cooling in offices, shops, and other commercial buildings will likely drop. How this nets out remains to be seen. What we know now, however, is that home cooling systems are already typically less efficient and clean than commercial and public ones.

2. Domestic refrigeration of food and drink. As restaurants, cafes, pubs, and other food service venues shut their doors, billions more people will be eating at home. In the U.K. in the first few weeks of the crisis, an additional $1.2 billion (1 billion British pounds) of food was bought and stored in fridges, freezers, and cupboards at home. The result is greater domestic demand for energy and F-gases to keep food and drink chilled, as well as an increase in sales of fridges and freezers to store the vast amounts of food being hoarded. Economic pressures and lack of supply impact purchasing choices and undermine demand for the most efficient, clean appliances. As with cooling in buildings, the systems and technologies for refrigeration at home are typically less efficient than in commercial and public settings. Therefore, as demand for refrigeration drops in restaurants, hotels, and the like, this reduction might be offset by the less efficient refrigeration technologies used at home.

3. Cold chains. With people on lockdown at home, and producers and supermarkets working overtime to deliver more food and drink, the “cold chains” associated with these deliveries are expanding. The U.K. government recently extended the hours when deliveries can be made. The U.K.’s major supermarket chains (as is likely the case in other countries) are also all on huge recruitment drives to ensure supply can meet the inflated demand. As the majority of refrigerated trucks in the world run on diesel or gasoline (very few are electric), we are likely to see a spike in emissions from these vehicles, both in terms of F-gases from refrigeration and tailpipe output.

4. Medical necessities. Surging demand for hospital beds already has many health care systems in turmoil. Patients need to be kept stable and drugs kept from spoiling, and doctors, nurses, and other care staff need working conditions that enable them to perform their best and save lives. Cooling systems can bring welcome relief during sweltering temperatures in packed hospitals. And tragically, the many that succumb to the virus will need to be kept cool in mortuaries. All of this will drive a macabre demand for cooling across the globe.

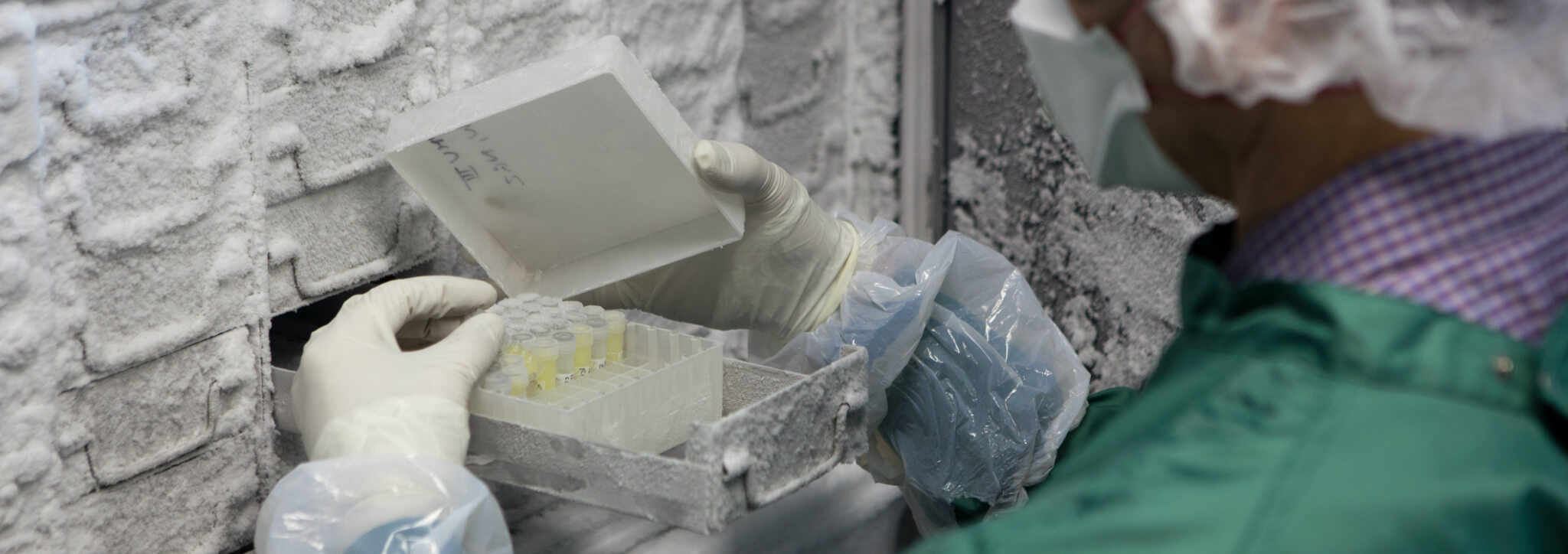

When, hopefully, a vaccine emerges for Covid-19, there will be a race to produce and dispatch doses to every corner of the world. The task of rapidly scaling up access to the vaccine will require a huge effort and will need to cater to a vast range of communities, from those in urban settings to those in the hard-to-reach locations, and everyone in between. Since many vaccines spoil if they’re not kept in a very specific temperature range, typically 2-8° C, this means that new cold chains will need to be established in certain parts of the world, in a way that is clean and efficient. If these vaccines are not kept cool, they will not be viable and we risk unknowingly releasing the virus back into society.

5. Data centers. The lockdown is shifting economic activity to the web as never before, driving an immediate spike in demand for energy in data centers. Energy consumption for cooling IT equipment in data centers can account for over 40% of total data center energy consumption, so efficient cooling for data centers is essential for reducing operating costs. Whilst this spike in demand may reduce when lockdowns are lifted, the shift in behavior, contracts, and agreed practices, whether working from home, average broadband speed contracted by households, or the use of Zoom for family interaction, will most likely not return to a pre-Covid-19 norm.

As with many of the unfolding impacts of Covid-19, plans are needed. Governments are responding with a sense of emergency. Businesses, banks, civil society, the U.N. system, and the general public are focused and listening like never before. The collective brain power of humankind will solve this problem, but decision-makers across the globe must solve it in smart ways that rebuild the global community so that it is stronger than before. When it comes to cooling specifically, the response needs to:

1. Be driven by urgently needed research. We need urgent analysis of the changes to and potential growth in demand for cooling in the areas identified here, along with the associated implications for climate pollution and the economic impact of cooling systems and appliances. Managing cooling-related costs and efficiencies in the economic recovery will support a quicker return to healthy economies and public balances. We must avoid locking in second-class cooling systems for decades to come, with their high pollution and operating costs.

2. Boost sustainable solutions. The response to Covid-19 needs to take advantage of business models and financial mechanisms that reap the rewards from more efficient, climate-friendly technology, such as “cooling as a service” (e.g. instead of buying a commercial fridge, a business can contract for a certain amount of cooling provided), and “pay as you save” (e.g. when a customer is provided with more efficient cooling technology, for example an air conditioner, and pays back the cost over time using the energy cost savings). Such models in turn make the climate-friendly cooling options, which tend to require a larger up-front investment, but with lower lifetime cost, more attractive to buyers.

3. Maximize job opportunities. Many cooling solutions, such as passively cooled buildings (through the use of efficient design and building materials instead of energy-consuming technology) and cooling by nature (green parks and spaces), create local jobs. Highly skilled professionals like engineers can help optimize cold chains and industrial processes, and the service industry can help with finance and contracts. More research and development can help establish the most feasible cooling solutions that serve people, the planet, and businesses. Taking a holistic and local view of how to provide cooling can support local jobs, rather than an “air conditioning for all” approach.

Perhaps more than ever, cooling is essential to the health and prosperity of the entire human race. Fortunately, cooling is already a huge industry — $134 billion per year according to The Economist — and staffed by a corps of dedicated cooling professionals in public service, business, academia, NGOs, international organizations, and philanthropy. Ideas, support, and collaboration are already plentiful, as encapsulated by the Cool Coalition, launched at the U.N. secretary-general’s 2019 climate summit. In overcoming this crisis, we must be ambitious and build back better.

Let’s seize this moment to make a cooler and more sustainable world possible for all.

We must dramatically reduce super pollutant emissions alongside carbon dioxide to achieve climate protection in line with the Paris goals.

The Paris Agreement says we should aim for global warming of “well-below 2 degrees,” and the IPCC special report on 1.5 degrees made that the standard to aim for. That’s such a tough goal on its own that it may not be obvious that there are options for the pathway to getting there – but differences in approach could mean millions of lives lost, or saved, between now and 2050.

In particular there is a choice about how to address short-lived climate pollutants, also called SLCPs or super pollutants. These substances, including black carbon, fluorocarbons and methane, are extremely potent, but have a short residence time in the atmosphere, and the fixes and alternatives are in most cases readily available. This means there’s a quick temperature response when cutting them; in the past this has been interpreted as meaning that whenever we get around to cutting them is fine, because there’s an immediate reaction.

However, that interpretation is based on two fallacies – first, climate policy has long ignored air pollution, and since super pollutants are also air pollutants or precursors to them, delaying cuts means putting up with more deadly pollution. Second, any warming we have to put up with is potentially dangerous – 1.5 degrees isn’t simply an end point where the pathway doesn’t matter – we want to cool down as soon as possible.

ClimateWorks has been trying to find a good way to communicate this point on the pathway, and then suddenly one was on front pages everywhere – flattening the curve of the coronavirus pandemic. The similarities are remarkably strong.

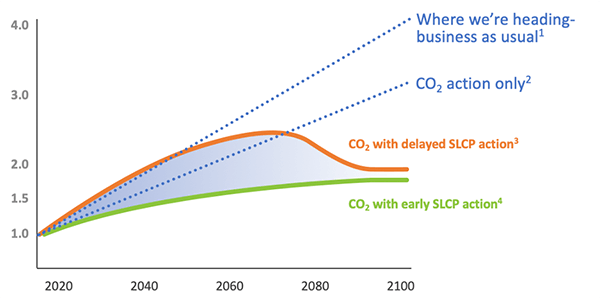

In the graphic below you can see the difference between taking action on CO2 emissions but waiting to deal with super pollutants, versus acting on them today – the latter flattens the curve, with all that implies. There is still warming, but it is smoother and levels off without a big early spike and overshoot of sustainable levels. According to a leading expert on this issue, Professor Drew Shindell, unless we reduce short-lived climate pollutants quickly, millions of people will suffer or die early from poor air quality, and will struggle to maintain food security against crop yield losses – consequences contained in the gap between the two curves.

Analysis shows that aggressive mitigation of super pollutants alongside CO2 will result in seven times the temperature impact by 2050 compared to working on CO2 alone – indeed, 87% of the reduction in temperatures that we can achieve by 2050 will be due to cutting SLCPs.

Analysis shows that aggressive mitigation of super pollutants alongside CO2 will result in seven times the temperature impact by 2050 compared to working on CO2 alone – indeed, 87% of the reduction in temperatures that we can achieve by 2050 will be due to cutting SLCPs.

Aiming at super pollutants also makes it easier to connect with policymakers and the public. It’s difficult to reach most people around the world about our agenda of meeting the Paris climate goals if we talk in terms of arcane global agreements, complicated science, or solutions that are out of reach for them.

However, air pollution is something that everybody understands – you can see it, and you can feel it in your lungs. Pollution is also a major preoccupation of governments – indeed a much higher one than climate in most parts of the world. By linking air pollution, health and greenhouse gases via super pollutants, we can enter a dialogue with countries and regions that are putting their development and health priorities first. Tackling super pollutant emissions will help improve health, agricultural yields, and economic progress.

We must dramatically reduce super pollutant emissions alongside CO2 to achieve climate protection in line with the Paris goals. Tackling SLCPs immediately will protect millions of people from harmful air pollution, and it will avoid temperature overshoot and the associated impacts on humans and the environment. It’s time we took fast action.

Three key principles should guide the industry's recovery.

It goes without saying that Covid-19 has turned the world on its head over recent weeks. Heartbreakingly, more than 120,000 people worldwide have already lost their lives to the disease. Around the globe, businesses are shuttered and people are locked down in their homes to slow the spread of the virus. The global economy is at a virtual standstill, pushing Americans into unemployment at a rate unprecedented since relevant statistics started being recorded in 1967. As people scramble to protect their livelihoods in this new reality, the U.S. government’s recent passage of a $2 trillion stimulus package should come as welcome news for many. Similar stimulus efforts are underway across the world to dampen the economic blow of near-global quarantine.

The aviation sector has been among the hardest-hit industries by Covid-19, with airlines projecting a $252 billion decline in revenue compared to 2019, a drop of over 40%. As airlines around the world seek government assistance to stay afloat, it’s no surprise that the U.S. stimulus package includes a $25 billion bailout for the aviation sector. As the industry charts its pathway forward, there are a few key principles that should guide its decisions to make it more sustainable, resilient, and consistent with global climate goals.

Protect jobs and livelihoods

First and foremost, the highest priority for the aviation bailout must be to protect workers’ jobs through this period of unparalleled uncertainty. Although the stimulus package caps executive compensation and contains provisions that airlines receiving public funds cannot lay off or furlough employees until September 30, United Airlines has already told staff to expect layoffs once the restriction period has passed, indicating that more needs to be done to protect thousands of livelihoods that are at stake. In the face of any systemic shock — be it a global pandemic or climate change — it is crucial to ensure that the most vulnerable do not bear the brunt of the impact, but rather that government and private sector interventions contribute to a more equitable future for all.

Bring sustainability to the forefront

When the federal government bailed out the automotive industry in 2008, funding was contingent on carmakers improving the fuel efficiency of their vehicles. While some lawmakers proposed similar provisions during recent stimulus talks, they ultimately did not make it into the final version of the legislation. Nevertheless, using the bailout funds in a way that supports both financial resilience and environmental sustainability is an important imperative, as recent discussions in the U.K. reflect. Aviation industry emissions are projected to triple by 2050, so returning to business as usual after Covid-19 recedes is simply not a viable option if the world is going to meet internationally agreed climate targets. Some measures, like the development of sustainable aviation fuels, can pay off for airlines in the long run in terms of building resilience by insulating them from wildly fluctuating prices in global oil markets. Indeed, across industries, smart climate decisions are often smart business decisions — same goes for aviation.

Today, the aviation sector has the rare opportunity to identify these synergies and fundamentally change course in order to act on them. Considering the importance of aviation in enabling the global economy to function, it is incumbent upon the industry to make the most of this moment of crisis to show that it can be a good global citizen for decades to come. With bailouts on the horizon in other countries and the sad possibility of additional bailouts needed in the U.S., it will be important to keep sustainability at the center of these ongoing discussions.

Think before we fly

As an organization dedicated to combating the global climate crisis, ClimateWorks is reexamining our own flying practices. While we know there will always be a need to travel given our global reach and work, we also know that we can reduce our aviation footprint in the months and years to come. The fact that companies and organizations continue to operate under lockdown conditions is proving every day that remote work is a viable option that can take the place of some in-person gatherings that come with both financial and environmental costs. If remote work does take the place of some business travel in the longer term, that would make for a leaner aviation industry overall, but right-sizing the sector can help eliminate unnecessary flying and bring the world one step closer to a livable climate for ourselves and future generations. Achieving a balance between the health of the aviation industry and the health of the planet will not be easy, but it is a balance that we need to pursue.

Past crises have shown us that despite these difficult times, the aviation industry will not only survive, but continue to thrive in the long term. The 9/11 terrorist attacks, for instance, caused a steep decline in air travel, but the industry recovered and went on to grow to unprecedented heights. The same goes for the 2008 global financial crisis. Covid-19 is a global menace to be addressed with the utmost seriousness, but a day will come when we are ready to take to the skies once again. Let us work now toward rebuilding the industry so that it is on stronger footing financially and environmentally, and is able to keep our globalized world connected in ways that enable our planet and people to thrive.

A message to our partners

Like you, ClimateWorks Foundation is monitoring the fast-evolving developments related to Covid-19 and we have taken a series of steps to protect the well-being of our staff, their families, our partners, and the wider communities in which we live. These steps are in accordance with guidance and recommendations issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other health agencies including the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

In this post, I wanted to share three decisions we’ve made that will impact how we work over the coming weeks. We will continue to monitor the situation closely and adjust our decisions based on the best available information.

First, effective Thursday, March 12, we are asking all employees in our San Francisco office to work remotely through the end of March and our office will be officially closed during this time. If you were scheduled to meet at ClimateWorks during this time, the ClimateWorks staff member(s) you were scheduled to meet with will be in touch with you to reschedule or set up alternative meeting logistics (e.g., via videoconference).

Second, we are rescheduling our larger convenings through the end of April. If you are scheduled to participate in a ClimateWorks-hosted gathering between now and the end of April, you will be notified in the coming days about specific changes. At this point, we have not made decisions to change any convenings taking place in May and beyond. We will contact you if that changes.

Third, we have suspended staff business travel to CDC Level 3 and Level 2 countries until further notice, and have strongly discouraged all other international and domestic travel unless business-critical.

Finally, while this global pandemic is impacting how we are working over the coming few weeks (and perhaps longer if necessary), it is not stopping our work. We have been preparing since last year to preserve “business continuity” in circumstances that would require staff to be out of the office for a period of time, and that preparation is paying off now. We know that all of our grantee partners are experiencing similar disruptions and prioritizing the health and well-being of their staffs and communities, and we fully support that focus. While there will be challenges for all of us to overcome in the weeks ahead, we are confident that ClimateWorks and the wider climate community will be able to continue our crucial work together in this unusual time.

If you have any questions, concerns, or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact the ClimateWorks team. We wish you all good health in the weeks and months ahead!