Youth4Nature is a grantee of our Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) Program

Lydia Halidi, 27, is a resident of Comoros, a country of several small islands off the coast in East Africa. She is working with local communities on mangrove reforestation and leading an awareness campaign on the impacts of deforestation and climate change.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Danilo Ignacio de Urzedo is working with Indigenous and rural communities in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado to promote ecological restoration, such as regrowing native plant species that can not only restore the Amazon rainforest, but also generate income for the local communities.

These are just two of over 90 stories young people from around the world have shared with Youth4Nature (Y4N), an organization run by and for youth in order to educate, empower, and mobilize their peers to advocate for ambitious, science-backed, justice-centered, and nature-based solutions to the climate and ecological crisis.

“I was tired of trying to make the issue fluffy and nice to engage people with, when really it is a crisis, and we need to engage with it like it is a crisis. I saw that here in Youth4Nature, and wanted to be part of it,” said Rachel Boere, Y4N’s Communications Director.

Since launching in May 2019, the organization has built a robust network of youth leaders for nature and climate through knowledge-sharing, storytelling, and capacity-building activities. It actively works to connect young people to decision-makers and experts at the intersection of the climate and nature movements. For instance, the group sent two global youth delegations to the 2019 U.N. Climate Action Summit in New York, and to the 2019 U.N. Climate Conference in Madrid, where they organized several workshops, participated in over 30 panel discussions, and delivered a three-day rotating storytelling exhibition. They also held bilateral meetings with decision-makers including officials from Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica, Nigeria, Kenya, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Canada, where they pushed to amplify and create more space for the voices of young professionals with hands-on experience fighting the climate crisis.

“Storytelling is a tool that not only helps to elevate the voices of young people, but serves as a platform to help collect and understand the learnings, the issues, and the actions that need to happen on the ground,” said Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe Dola, the Storytelling Director at Y4N.

They are also pivoting their mission and work to be more justice centered.

“There’s glaring inequality on whose knowledge counts, whose voices count, who gets the seat at the decision-making table. It’s mostly global north-dominated, and within that too, more middle class and privileged backgrounds. In our next phase, we are building solidarity with Indigenous youth, hosting webinars, and doing other outreach with them and other communities that are suffering the impacts of climate change now,” said N’Dombaxe Dola.

With a capacity-building grant from the ClimateWorks Foundation in partnership with the Climate and Land Use Alliance, the organization is among other things, expanding its capacity to reach youth from all over the world by hiring regional directors.

“I’m really proud to support Y4N in their efforts to center climate, nature, and justice issues. I saw Marina (Y4N founder) speak at the New York Climate Week last year, and was completely inspired by her. We definitely need more youth voice and expertise in the nature and climate movements,” said Tracy Johns, Program Officer, Climate and Land Use Alliance.

The one-year grant from the ClimateWorks Carbon Dioxide Removal program will support Y4N to launch region-specific engagement strategies, a knowledge-sharing and capacity-building webinar campaign, and grow the organization’s network and presence as a resource hub for youth around the world on nature-based solutions. They have also just launched their new Storytelling Campaign, #YourStoryOurFuture, which is amplifying the urgent messages, community-centred action, and solution-oriented work that youth are leading for nature, biodiversity and climate. In the year ahead, they hope to source a story from every country in the world.

We are very excited to see the organization grow and enable more youth voice and youth action for nature and climate!

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented damage to the global economy, dramatically impacting the movement of people and disproportionately impacting workers most vulnerable to economic downturns. In India, this is most acutely evident in the mass migration of daily-wage workers from urban to rural areas at the height of Covid-19 shelter-in-place, and seeking work back in the cities as restrictions were lifted. Compounding their economic crisis is the lack of access to safe, affordable, and clean transportation options.

As usage of public transportation is likely to continue plummeting, demand for trips by three-wheelers is expected to grow in comparison to other shared mobility options. And thus, at this intersection of health, mobility, and the economy lies an opportunity to help sustain livelihoods in a way that provides clean transportation to the masses: electrification of India’s ubiquitous rickshaw.

A rickshaw is traditionally a pedal-run or motorized three-wheeled vehicle that operates as an informal taxi and dominates passenger mobility in India. Roughly 8 million auto-rickshaws are on the roads across the country and they are the main source of daily income for millions of drivers as well as a major mode of transportation across income groups.

Electrification of fossil-based rickshaws and the integration of locally assembled e-rickshaws (battery-operated) is the key to clean energy transition. However, high upfront costs, lack of financing options, and lack of awareness about supportive policies and charging options remain major barriers.

Considering the scale of the opportunity to sustainably empower vulnerable communities, this is an ideal moment to break down barriers to rickshaw electrification and catalyze a transition toward just, equitable, and inclusive transport across India.

Rickshaws for air, health, and climate

In 2017, poor air quality contributed to 1.2 million premature deaths in India. Accelerating the electrification of rickshaws could improve millions of lives by reducing respiratory illnesses and premature deaths related to air pollution. In the long run, electrification of three-wheelers will have huge climate benefits given that they were the fastest growing segment of the automotive market before the pandemic, while auto demand remained depressed during this period. While the sales may be impacted by the economic downturn, three-wheelers are still in the lead.

Currently, there are an estimated 210 million two- and three-wheelers in India, or 83% of all vehicles, compared to 2 million private light-duty vehicles. The volume of these small vehicles is a major source of growing greenhouse gas emissions, roughly 20% of all transport-related emissions in the country. Achieving 80% penetration of electric three-wheelers by 2030 will lead to an estimated 195 million tons of net CO2 savings over the vehicles’ lifetime. Prompted by national FAME I and FAME II regulations, India is already home to 1.5 million battery-powered e-rickshaws, which transport about 60 million people per day. Philanthropic support can help foster favorable conditions for these vehicles to reach 80% penetration by convening diverse stakeholders, enabling advocacy and shared learnings across geographies, and facilitating innovation in financing mechanisms.

Rickshaws: Market edge for energy transition

The commercial purpose of rickshaws provides a key advantage for electrification, as drivers already have an incentive to keep the operating costs down, and fleet operators to innovate for improved efficiency. Similarly, mobility service providers are an ideal market-scaling mechanism, as they are already offering renting options to drivers across major cities.

Commercial operators can also facilitate the roll-out of charging infrastructure, servicing and maintenance depots, and battery management practices, as seen through a rise of innovative start-ups with battery swapping and operations services. Research shows that, in comparison to a light-duty vehicle, electric three-wheelers can achieve cost parity with fossil-based counterparts much faster due to lower maintenance costs and power requirements, resulting in lower dependency on charging infrastructure. As charging options to service three-wheelers grow, this is expected to yield a cascading benefit to two-wheelers, by supporting higher customer trust and encouraging uptake.

Current government subsidies coupled with additional financing mechanisms can accelerate electrification of rickshaws, generating additional economic benefits for personal and commercial ownership. For instance, research by CRISIL, a global analytics company, estimates that even though the post-subsidy acquisition cost of a lithium-ion powered e-rickshaw is broadly the same as an combustion-driven three-wheeler, the lower running cost can lead to considerable savings for the driver each day. As the market is starting to expand through early adoption of electric mobility and manufacturers are ramping up production and offering new e-rickshaw models, breaking down the remaining barriers in first-mover markets, like small electric vehicles, will accelerate the transition to fossil-free mobility.

Philanthropy for rickshaws

The many benefits of electrifying three-wheelers — such as financial inclusion, access to low-cost mobility, reduced emissions, improved air quality, and economic benefits — coupled with healthy market projections, underscore the significance of greater collaboration between the Indian government and the automotive industry in supporting and accelerating the transition in this mobility segment.

Philanthropic investment in this space should focus on three key areas:

- Name the stakeholders and the roadblocks. The complexity of the regulatory environment, economic value of the informal mobility market, and past efforts at electrification, require a comprehensive assessment of the key players in the space, social value associated with electrification of three-wheelers, approaches that have been tested, and the resulting gaps that need to be closed. The landscape assessment should look into questions such as:

- What public-private interventions and financing options can support and accelerate adoption, especially among low-income groups?

- For low-income drivers, what are some of the benefits associated with renting as opposed to owning three-wheelers? Are there any case studies from fleet owners in major cities?

- What set of policies can enable more registration of electric three-wheelers without impacting livelihoods?

- Bring the stakeholders together. The dialog platform bringing together representatives from government, industry, the NGO community, and labor or representation from community of informal workers, should work to advance key policies, specifically:

- An optimal regulation framework for three-wheelers,

- An incentive structure to support uptake,

- Financing structures for drivers to transition to electric rickshaws,

- Innovative business models both for renting and operating three-wheelers, as well as battery swapping, and many others.

- Make it work. Establish a comprehensive pilot in a champion city in order to build on lessons learned from past efforts and to showcase a legitimate pathway for electrification of three-wheelers in other cities.

The ‘last mile’ on the path toward reaching 100% electrification of rickshaws will require a national-level policy with at least two targets: (1) encouraging manufacturers to produce and sell more electric two- and three-wheelers, through a direct mandate at the state or national level, and (2) disincentivizing the purchase and use of fossil-based rickshaws.

The right set of policies and partnership, coupled with current high ambition, can lead India from economic recovery to electric, inclusive rickshaw mobility. Philanthropy can leverage its convening power to bring together diverse stakeholders with the goal of unlocking the remaining barriers to an accelerated electrification of rickshaws.

Clean power is crucial to a safe climate

To achieve greenhouse gas reductions in line with the most ambitious goals of the Paris Climate Agreement, 65% of electricity must be carbon-free by 2030, eventually transitioning to net-zero or a carbon-free electricity grid by 2050.

While global renewable energy capacity has grown tremendously in the last two decades, the utilization of renewables in power generation has not reached the scale needed to limit global average temperature rise to 1.5°C. Even though the transition to clean, emissions-free power is still possible, the window for action to avoid catastrophic climate change narrows every day. To succeed, the transition of the global power sector toward clean renewable energy needs to accelerate and scale rapidly.

Fortunately, renewable energy technologies are now cheaper than fossil fuels and there are proven regulatory policies and operational approaches that can effectively integrate large shares of renewable energy into power systems. More importantly, there is growing political will to take these actions. Looking ahead, the challenge is in sharing all of this accumulated know-how with power sector professionals around the world and building their capacity to act on it.

The Clean Power Hub’s role in expanding renewable energy

The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) and ClimateWorks are proud to support the Clean Power Hub, an innovative new platform to enable broader and faster sharing of clean power knowledge and skills.

“The rapid transition to clean power around the world is essential if we are to tackle climate change and deliver public benefits such as air quality,” said Sonia Medina, executive director for climate change at CIFF. “The Clean Power Hub will ensure that the practical tools and steps needed to radically increase the share of renewable electricity in a country are available and accessible to all those who need them, supporting action and accelerating the transition with the aim of creating a climate safe future for children.”

The initiative focuses on defining and streamlining the work that power sector professionals need to do to transition to cleaner power systems and provides free and practical guides on how to get it done. It amplifies the expertise of the world’s leading institutions for clean power technical assistance and capacity development through state-of-the-art online learning and skill-development tools.

The Clean Power Hub helps practitioners to execute the clean power transition, directing them to the resources that advance that work. Throughout these guides, the Clean Power Hub gives its users free access to models, tools, executive education, peer-to-peer communities, and expert consulting services. While much of the Clean Power Hub and its content are globally relevant, its initial geographic focus is Southeast Asia.

“The Clean Power Hub is an excellent, practical new tool,” said Fabby Tumiwa, executive director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform, a leading Indonesian think tank supporting the clean energy transition. “We expect to use the Clean Power Hub to help educate our partners, and our own staff, on the work needed to build a resilient, low-carbon energy system.”

Funding partner

Children’s Investment Fund Foundation

Implementing partners

Propel Clean Energy Partners

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Grantham Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, Imperial College London

Learn more

Contact us to learn more about the Clean Power Hub.

5 others

Countries agreed to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and ideally 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The latest science shows that emissions will need to drop by half by 2030 and reach net-zero by mid-century to meet this goal and prevent the worst impacts of climate change.

The question is: Are we on track to meet climate targets by 2030 and 2050?

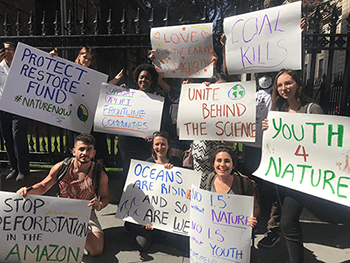

A report from WRI and ClimateWorks Foundation found that in all but a couple of cases, progress is happening far too slowly for the world to meet its emissions-reduction targets – and in some cases, we’re moving in the entirely wrong direction.

The State of Climate Action report assessed 21 indicators across six key sectors. Of all the indicators assessed, two show a historical rate of change sufficient to meet both 2030 and 2050 targets; 13 indicators show change headed in the right direction, but too slowly; and two show change headed in the wrong direction altogether. Data are incomplete to assess progress in four indicators.

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) consortium designed benchmarks for the power, industry, buildings and transport sectors, while WRI designed indicators for the forest and agricultural sectors. All benchmarks were informed by multiple lines of evidence to account for recent developments, assess feasibility and ensure compatibility with the Paris Agreement.

Here are some of the most significant mitigation opportunities across the power, buildings, industry, transport, forests and agriculture sectors that will be needed to meet global GHG emissions targets:

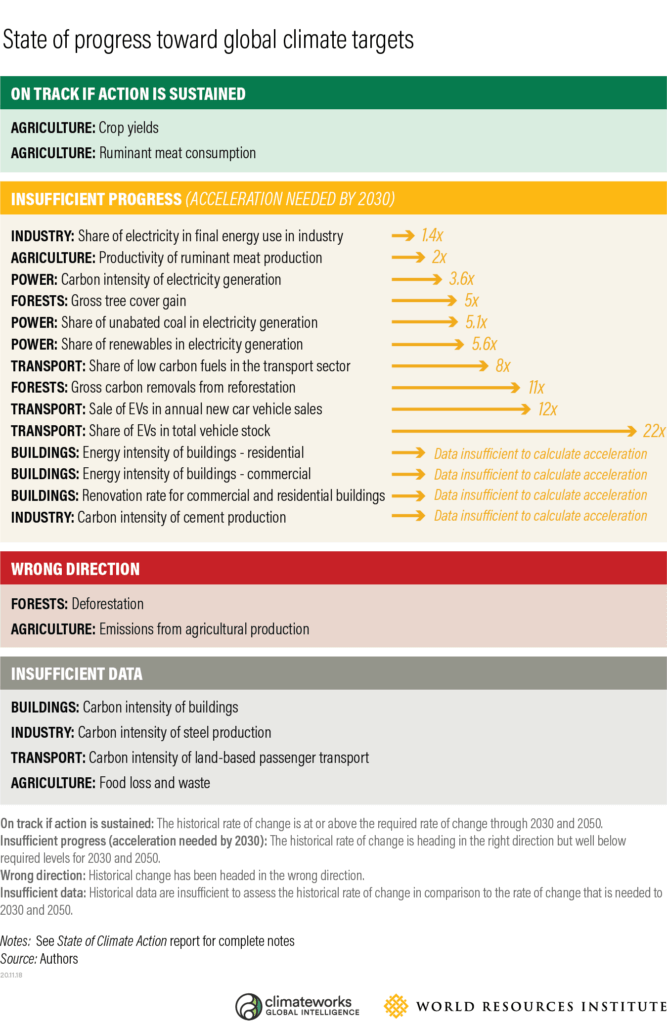

1. Power Sector: Increase renewables 6 times faster and phase out unabated coal 5 times faster than current rates by 2030.

Renewable energy is now the generation technology of choice, making up 72% of new capacity in 2019. The rate at which it is being added globally has been increasing year over year, and its share of total electricity generation reached around 27% in 2019.

While there has been a tremendous acceleration in renewable energy, to meet 2030 and 2050 climate targets, the pace of change will still need to increase by a factor of five.

Each county’s pathway toward achieving these milestones differs depending on their starting point. For example, China and India are starting with higher shares of coal-fired power, at 67% and 74% in 2018. In other countries — Brazil, for example — the share of renewables in total electricity generation is already much higher than the global average, at more than 80% in 2018, due to abundant hydropower, but electricity demand is also expected to grow.

At the same time, existing coal-fired power plants need to shut down and no new ones should be built to avoid locking us into a carbon-intensive future. Globally, coal currently provides 38% of electricity, but by 2040, electricity from unabated coal needs to be phased out[footnote tooltip=”Across low and no-overshoot 1.5C scenarios assessed in the SR15, unabated coal constitutes 0.5% of total electricity production in 2040.”][/footnote].

Governments are increasingly recognizing the health and cost benefits of moving away from coal: Retirement of coal plants has increased — from 2 GW in 2006 to 34 GW in 2019 — but new coal plants continue to be built, largely in countries with increasing demand for electricity.

2. Building Sector: Accelerate the renovation of existing buildings and construct new buildings at much higher efficiency standards.

Globally, building operations (excluding manufacturing and construction) account for 30% of energy use and 27% of energy-related CO2 emissions. Existing buildings must be renovated to increase energy efficiency and improve carbon intensity, but the world is not doing so quickly enough. Current rates of renovation for both residential and commercial buildings fall between 1% and 2% per year on average; to achieve climate goals, they’ll need to reach 2.5-3.5% per year by 2030 and with much more significant energy-efficiency improvements.

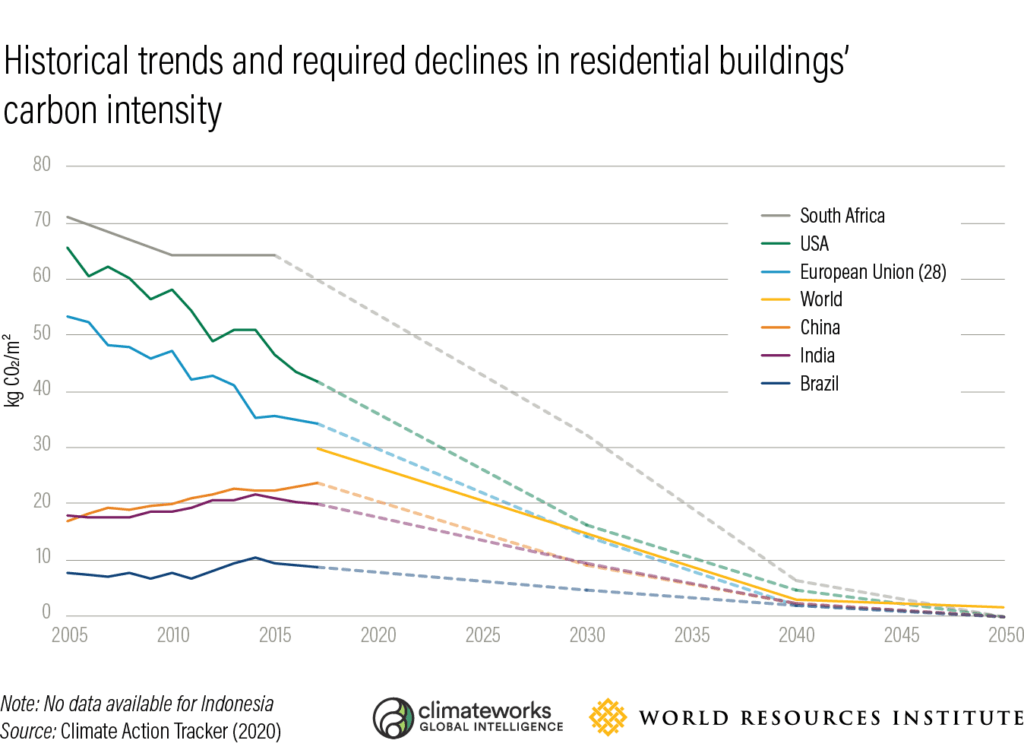

Relatedly, the carbon and energy intensity of existing residential and commercial buildings have been gradually falling across major emitting economies, with a few exceptions. But this decline needs to happen much faster in most countries to be on track for a 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) future.

In addition to renovating existing buildings, all new buildings in all countries need to be of high energy-efficiency standards and equipped with heating and cooling technologies that either are or can be zero-emissions.

In many countries, much of the building stock that will exist in 2050 is yet to be built. These countries face the challenge of expanding building stock while also improving the energy and carbon intensity of existing buildings. Heat pumps, solar thermal water heaters and high thermal building standards are key to keeping energy demand and emissions low while providing comfortable living standards.

3. Industry Sector: Significantly reduce emissions intensity of steel and cement by 2050.

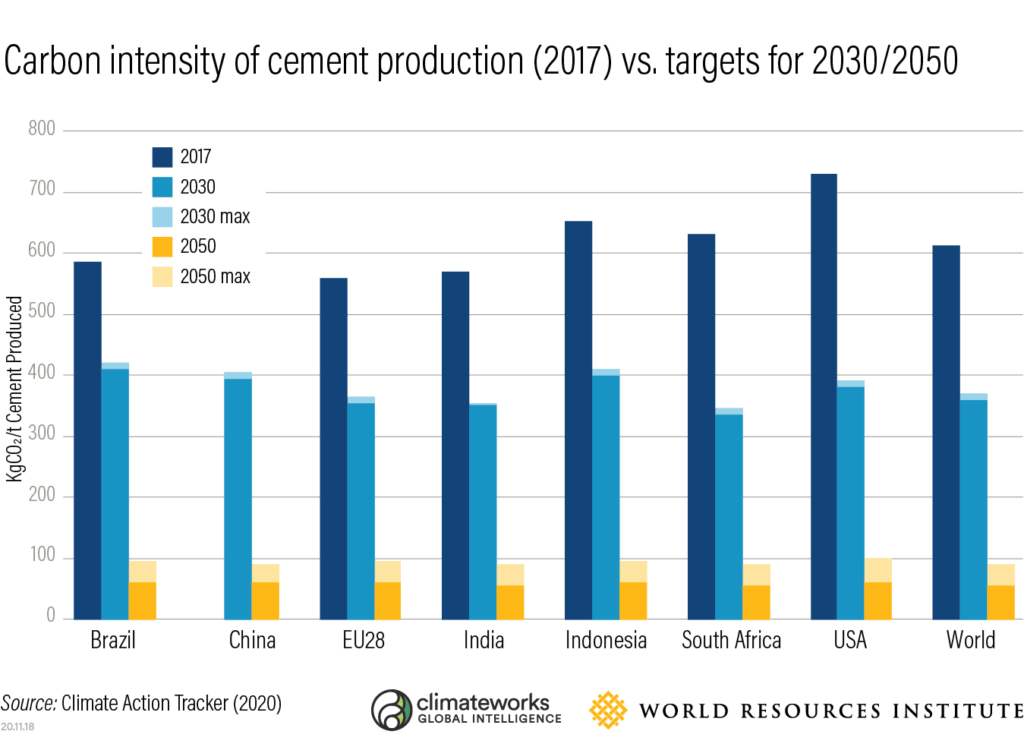

Emissions from the production of cement and steel make up nearly half (44%) of industrial emissions. To meet climate goals, cement emissions intensity will need to drop 85-91% globally and steel emissions intensity 93-100% by 2050.

The global average carbon intensity of cement has remained flat over the past eight years, with some countries (like the United States) actually seeing increases in emissions intensity. CO2 emissions from steel production have been declining slightly over the same time frame in most major-emitting countries, but will need to rapidly decline if we are to meet climate targets.

A variety of options exist for the decarbonization of steel and cement production and they will need to be deployed together rapidly in the coming decades. Key options include increased recycling of scrap steel, switching to hydrogen for steel production, using alternative fuels in cement kilns and reducing the share of clinker in cement. Additional behavioral changes, such as reducing demand for these products, increasing the lifetime of buildings and other structures, and increasing the recycling and reuse of materials, can all help to further drive down emissions intensities.

4. Transport Sector: Adopt electric vehicles 12 times faster than current sales rate by 2030.

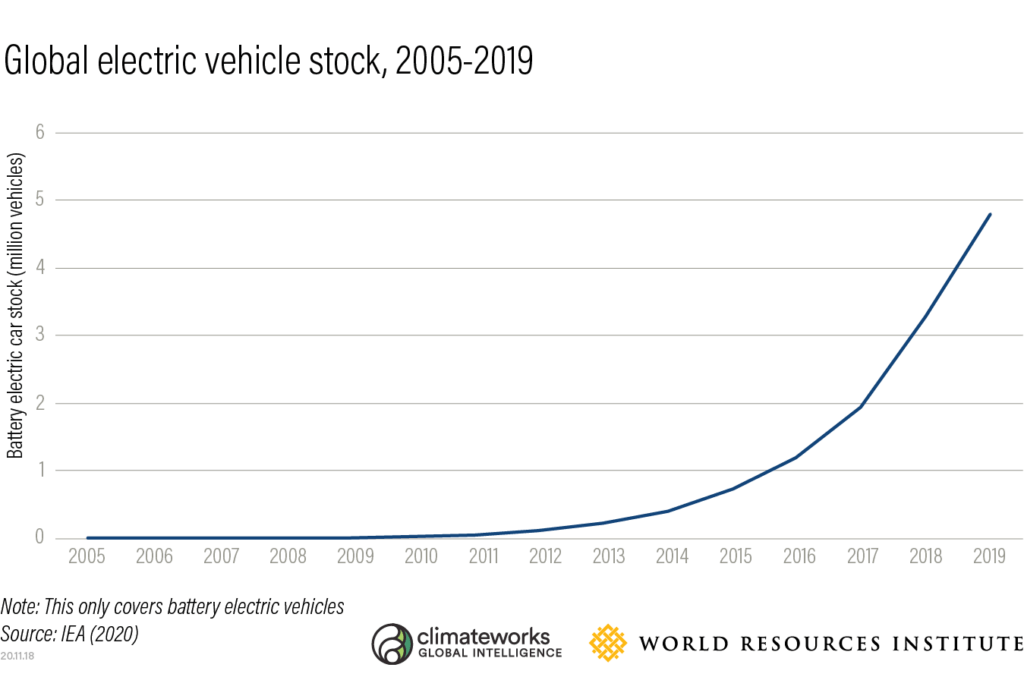

While there are a number of avenues to move toward more sustainable transport — like investing in public transport and making cities more walkable — replacing traditional internal combustion engine vehicles with electric vehicles (EVs) can reduce emissions from passenger vehicle transport, provided the grid powering them is also on a path to decarbonization. (Where this is not the case, low-carbon fuels must play a role.)

EVs currently make up a small percentage — roughly 1% — of the global passenger vehicle stock. But they’ve grown rapidly over the past five years and will likely accelerate further. This expansion is especially pronounced in countries with supportive policies, like China and Norway. In the latter, EVs made up 56% of new vehicles and 13% of the total vehicle stock in 2019.

As the cost of owning EVs gets more competitive with traditional vehicles and governments increasingly enact supportive policies, progress is moving in the right direction. However, if climate targets are to be met, the rate of recent EV sales globally will still need to accelerate by a factor of 12 for us to get to a fully electrified vehicle fleet and decarbonized transport sector.

5. Forests: Drastically slow deforestation and increase tree cover gain five times faster by 2030.

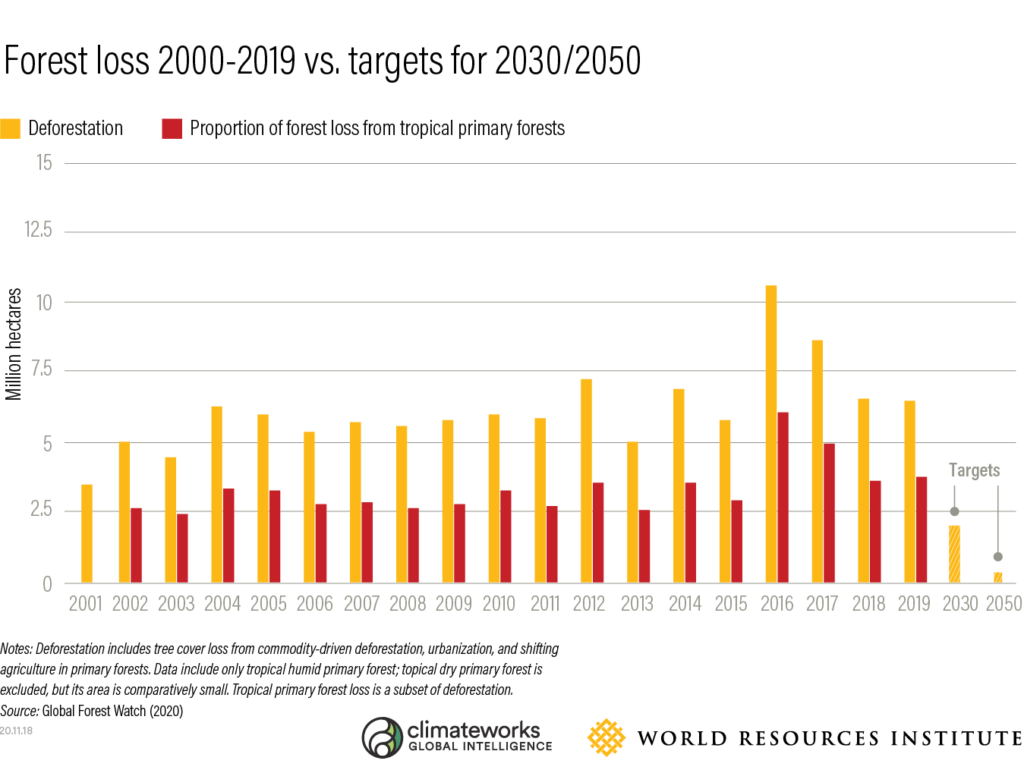

Forests can be an emissions source when they are cut down or an emissions sink when more trees are added to the landscape. To ensure that forests are part of the climate solution, we need to significantly reduce deforestation — particularly tropical deforestation — and increase the rate that trees are added to the landscape by up to five-fold.

Deforestation has increased on average since 2001. Particularly concerning is loss of primary forests (see red bar below), which are irreplaceable in terms of biodiversity, ecosystem function and carbon sequestration.

While commitments to reduce supply chain deforestation have been increasing, they have not yet seen much success. Commitments to restore degraded landscapes are already nearly on track for the 2030 target (countries have committed to restore 349 million hectares[footnote tooltip=”Based on forthcoming article by Susan Cook-Patton et al. “][/footnote], compared to the 350 million hectares that need to be restored by 2030 to meet climate goals). But of course, countries will need to ensure that finance, incentives and politics align to turn commitments into concrete action.

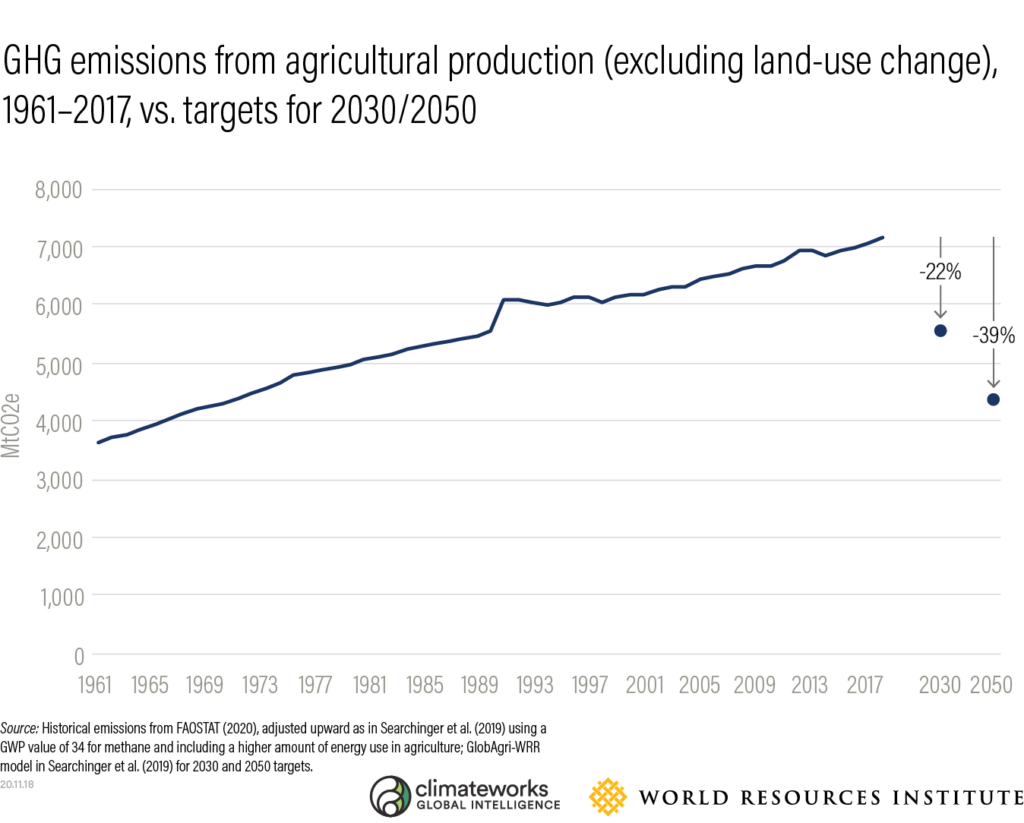

6. Agriculture Sector: Accelerate productivity gains and shift consumption patterns to feed a growing population while preserving forests.

Improving land use efficiency is critical to meet the food demands of a growing population and achieve large-scale reductions in deforestation and increases in reforestation. At the same time, it will be essential to slow the rate of growth in food and agricultural land demand by reducing food loss and waste, shifting high-meat diets toward plants (and especially away from emissions-intensive beef and lamb), and avoiding further expansion of biofuel production.

Of the 21 indicators assessed in our analysis, the two that are on track to meet 2030 targets (if recent rates of action are sustained) are both in the agriculture sector: crop yield growth and ruminant meat consumption. However, while these two global-level indicators are on track if current action is sustained, there is high variability at country and regional levels that tells a more nuanced story.

For example, crop yield growth will need to accelerate more than 10-fold in sub-Saharan Africa to meet growing food demands without cropland expansion and loss of forests and savannas. And to meet the ruminant meat consumption target in an equitable way, the Americas and Europe would need to reduce their consumption 3 times faster than the rate over the past five years to provide room for low-income countries to modestly increase their consumption.

And one important overall indicator — total GHG emissions from agricultural production — is still moving in the wrong direction.

How Countries Can Secure a Low-carbon Future

Our current state of progress is significantly out of pace with the required transformations.

While this may seem daunting, it is achievable. The technological advances we’ve seen with cars, phones and computers once seemed impossible, too. A rapid transition to a zero-carbon future offers the same opportunity – but only if properly nurtured with the right policy, incentives, finance and other support.

Ahead of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) negotiations in Glasgow next year, countries should submit stronger national climate commitments under the Paris Agreement and develop long-term, low-emissions development strategies across all sectors. Depending on how ambitious they are, national climate plans could lock us into a carbon-intensive trajectory or accelerate us toward a safer, prosperous and more equitable future.

In addition, the rapid transformation needed will require significant financial investments, technology transfer and capacity building for developing countries. While climate finance has increased significantly in recent years, it is not at the scale needed to revolutionize our energy and transportation systems, accelerate energy efficiency and protect forests. Estimates indicate that we’ll need between $1.6 trillion and $3.8 trillion per year through 2050 for the energy transformation alone. In addition, changes put in place to realize a zero-carbon future will need to be done so in a way that they are durable and in a manner that is just, equitable and ensures prosperity for all.

As the State of Climate Action report details, options exist in all sectors to align GHG emissions trajectories with what the science says is necessary to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Now, it’s up to countries, businesses and others to put in place policies, incentives and financial investments to get us on the right track.

With a $50 million grant from the Bezos Earth Fund, ClimateWorks will scale up global initiatives to advance climate-friendly commercial trucking, marine shipping, and cement and steel production.

Today, ClimateWorks is pleased to announce that we are among the first grant recipients of the Bezos Earth Fund. Our grant will focus on three critical areas for climate action: zero-emission trucks, zero-emission shipping, and climate-friendly cement and steel production.

These initiatives offer tremendous opportunities to achieve large-scale emissions reductions, catalyze new technologies and economic growth, and benefit people and the planet. To realize these goals, ClimateWorks is applying more than a decade of experience and partnerships to drive coordinated action and results around the world.

Working together, we can achieve the Paris climate goals, but we need to do more, faster, and philanthropy has a crucial role to play. Global climate mitigation philanthropy must grow — from less than 2% of global giving today, with work on equity and justice receiving a very small fraction of that total — to the scale required to meet the challenge. The Bezos Earth Fund is an essential new addition to the climate philanthropy community. Its $10 billion commitment is game-changing, and its initial grants will support critical progress to mitigate climate change and improve lives. We look forward to working with the Earth Fund as ClimateWorks continues on our mission to end the climate crisis by amplifying the power of philanthropy.

As the world recovers from Covid-19, we have extraordinary opportunities to build back better by taking bold actions to end the climate emergency, advance racial and social justice, and protect the thriving planet we all share. With the Bezos Earth Fund’s support, ClimateWorks and our initiative partners are committed to driving progress in these areas through the critical initiatives described below.

Catalyzing Zero-Emission Trucks

Commercial trucks are the lifeblood of our global goods movement system. They also produce about one-third of global transport climate pollution and a disproportionate share of the air pollution that damages human health. This project will leverage advances in battery technologies and the policy precedent recently set by California to catalyze a transition to zero-emission commercial trucks through corporate leadership and smart government policy. This project is a key piece of ClimateWorks’ global strategy to accelerate zero-emission road transport.

As part of this strategy, ClimateWorks supported a coalition that helped California adopt a groundbreaking clean truck policy in 2020 that will ensure that half of all new trucks sold in California are zero-emission by 2035. This was followed by an agreement between California and 14 U.S. states plus the District of Columbia to pursue 100% sales of zero-emission trucks before 2050, and a California governor’s order targeting 100% zero-emission trucks by 2045.

These leading-edge policies offer national and international models as governments and businesses look to meet their climate commitments, lead on clean technology innovation and jobs, and dramatically reduce air pollution that disproportionately affects the health of communities living near ports and freight corridors. This project will support broad coalitions to encourage uptake of similar policies in other leading jurisdictions.

Launching Zero-Emission Ships

Fully 90% percent of the world’s freight moves by ships, generating planet-warming emissions that rival that of U.S. coal. And air pollution from ships damages human health; experts estimate that emissions from international shipping lead to more than 60,000 deaths a year.

To date, governments and the industry have set long-term goals to decarbonize shipping, but there aren’t enough ships on the water using clean fuels to give confidence that those goals can be reached.

Through this initiative, we will work with partners around the world to establish demand for the first zero-emission ships to be put on the water, with the first ports ready to provide clean fuels. Partners will include leading businesses and ports, experts in the technologies and policies needed to eliminate shipping emissions, local environmental justice groups seeking to reduce pollution in their communities, and other stakeholders.

Creating Markets for Climate-Safe Cement and Steel

We cannot solve the climate crisis without dramatically reducing emissions in the industrial sector — to nearly zero by 2050. Today, cement and steel together generate about six gigatons of CO2 per year, roughly 15% of global CO2 emissions. About half of cement and one-fifth of steel is purchased with tax dollars to build roads, railroads, water systems, public buildings, and other public works. If governments preferentially purchased cement and steel with a low carbon footprint, they would create enormous new markets and business opportunities that could dramatically accelerate the deployment of clean cement and steel.

Since 2017, ClimateWorks has been working with partners to help governments use public procurement to create markets for low carbon building materials. Early work enabled the passage of the Buy Clean California Act, the first law of its kind, which limits CO2 emissions produced in the manufacture of key building materials used in any construction project funded by the state of California — worth well over $100 billion in the next 10 years.

This initiative will work with stakeholders to bring the Buy Clean approach to other jurisdictions to expand the market for green steel and cement, drive business innovation, and reduce the emissions that cause climate change.

Looking ahead

Climate change is one of the greatest threats facing humanity, and philanthropy has a pivotal role to play in meeting this threat. Reacting to the significance of the Bezos Earth Fund and its initial grantmaking, Larry Kramer, president of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and a ClimateWorks board member, stressed the urgency of the challenge, saying, “these grants to ClimateWorks and other leading climate-focused organizations are a tremendous boost at a pivotal moment.” We agree and look forward to making big, near-term gains to set trucks, ships, cement, and steel on the path to a sustainable future in which everyone can thrive.

After a long national debate about the direction of the country, American voters have spoken. On January 20, 2021, Joe Biden will be sworn in as the 46th president of the United States, and Kamala Harris will make history as the first female, African American, and South Asian American vice president.

Although control of the Senate will remain in question until two runoff elections in Georgia are settled, one thing we know for certain is that under the new Biden-Harris administration, the U.S. will rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement and quickly and constructively re-enter the global effort to end the climate crisis.

This is a decisive decade for action to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. While the last four years saw a series of setbacks to U.S. climate progress, and the nation remains deeply divided on many issues, the significance of resurgent U.S. climate action and leadership is profound. President-elect Biden recognizes that climate change is an existential threat and has pledged to cut U.S. climate emissions to net-zero by 2050. He will work to restore and reimagine America’s international partnerships and will engage leaders of other major carbon-emitting nations to accelerate climate action. The U.S. is coming back to the table, and that’s important.

In his victory speech, the president-elect said: “And we lead not by the example of power, but by the power of example. I’ve always believed we can define America in one word: Possibilities.”

At ClimateWorks, we also believe in the inherent value of leading by example and in the power of possibilities. In the past four years, the prospect of meeting the Paris climate goals was at times dim, but civil society, leading governments, and forward-looking businesses helped light the path of possibilities toward a sustainable climate and a brighter future. In the coming months and years, we will stand shoulder to shoulder with allies in civil society, philanthropy, and the public and private sectors to continue to pursue possibilities and drive the change we need to protect the climate on which we all depend.

These are times of challenge and change. We are confident that with bold vision, collaborative action, and expansive optimism, the world will rise to the challenges we face. In this spirit, we look forward to continuing to work with partners to end the climate crisis and ensure our planet is a thriving home for all beings for generations to come.

Through his brilliant science and tireless advocacy, Dr. Mario Molina helped the world successfully respond to the first global environmental crisis, the threat of chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) to the planet’s protective ozone shield. He shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in discovering this threat.

Sadly, Dr. Molina left us on October 7, 2020. But he did not leave us empty-handed. A true gentleman and optimist, Mario not only set us on the path to environmental stewardship and justice, he left us a roadmap for how to solve climate change in time to prevent climate chaos.

In 2009, Mario co-authored a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences titled Reducing abrupt climate change risk using the Montreal Protocol and other regulatory actions to complement cuts in CO2 emissions. This paper set out the first roadmap for fast mitigation under the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer and other venues to solve the next great threat to the global environment, climate change. Just as he had for the Montreal Protocol, Mario worked hard behind the scenes on what became the Kigali Amendment, agreed in 2016. By taking on the super-greenhouse gas hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) that replaced the ozone-depleting CFC and HCFC, which were also strong greenhouse gases, the Kigali Amendment cements the Montreal Protocol as the most impactful climate change treaty.

The Kigali Amendment also recognized the importance of ensuring a transition to climate-friendly and energy-efficient cooling equipment. And Mario co-chaired the steering committee on the UNEP and IEA Cooling Emissions and Policy Synthesis Report, which showed that the combined strategy to improve energy efficiency of cooling equipment while phasing down HFC refrigerants under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol is one of the biggest mitigation opportunities available today.

Mario was hard at work updating that 2009 paper to show how close the world is to a catastrophic hothouse, and how we can use the Montreal Protocol to prevent this by cutting the short-lived climate pollutants and protecting our carbon sinks. He promoted the need for speed to slow feedbacks and avoid tipping points:

“And let us be clear: By “speed,” we mean measures—including regulatory ones—that can begin within two-to-three years, be substantially implemented in five-to-10 years, and produce a climate response within the next decade or two.”

We’re the ones who have to carry on. But we have his roadmap and his reminder of the need for speed.

###

To learn more, check out Living on Earth’s story about Dr. Molina’s remarkable life and contributions.

Indonesia is among the top 10 greenhouse gas emitting countries globally, and is the largest economy within Southeast Asia, one of the fastest-growing regions in the world. As a rapidly developing country (the World Bank upgraded it to upper-middle-income status earlier this year) with the world’s fourth-largest population, Indonesia is a key country for deep decarbonization strategies to meet the mid-century goals of the Paris Agreement. The development pathway Indonesia chooses for itself will have broad ramifications for the Southeast Asian region and the rest of the world. While Indonesia is not on track to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, there are many opportunities for Indonesia to enhance its climate ambition and avoid locking itself into a high-carbon development pathway with environmental degradation and stranded assets. By pursuing the right policies today, Indonesia can emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic with a vibrant economy without sacrificing its environment.

Why climate action

Climate action is important for Indonesia both to reduce its exposure to the physical risks of climate change and to realize the social and economic benefits associated with reforms across key sectors. With 81,000 km of coastline across its many islands, Indonesia is vulnerable to sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion, which may impact freshwater availability and agricultural production in conjunction with changes in precipitation patterns. At the same time, Indonesia has a large youth population, is busy building infrastructure, and has maintained solid economic growth for a number of years. If Indonesia wishes to escape the middle-income trap and continue its upward trajectory, it needs to move beyond natural resource extraction and invest in the industries of the future. Fortunately, there are many options that a forward-looking policymaker could advocate for. The five actions outlined below are not exhaustive, but are among the many positive steps Indonesia could incorporate into an update to its Long-Term Strategy to enhance its climate ambition and promote a sustainable recovery.

1. Decarbonize land transport

Transportation — both personal mobility and freight activity — is not only the largest source of energy demand in Indonesia, it is also responsible for dangerous levels of local air pollutants that reduce life expectancy in Indonesia by over one year on average. Electrification of two-wheelers, buses, cars, and trucks, and more stringent fuel economy standards for fossil-powered vehicles will drastically improve air quality and health outcomes while reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transport. Fortunately, the government recognizes the importance of clean transportation and President Joko Widodo has issued presidential regulations in 2019 and 2020 that set targets for electric vehicle adoption and provide incentives for local electric vehicle production.

2. Enable low-carbon industry

While Indonesia should be congratulated on recently reaching upper-middle-income status, there are warning signs for the economy that merit a considered policy response. After rapidly increasing through the early 2000s, foreign direct investment into Indonesia has stagnated over the last several years and the economy is still highly dependent on extractive industries such as crude palm oil and coal production. Escaping the middle-income trap will require a concerted effort to promote the industries of the future that will allow for Indonesia to be competitive on the global stage. Leveraging its world-class nickel and copper deposits, Indonesia is hoping to become a hub for battery electric vehicles, which would both stimulate domestic manufacturing and help reduce Indonesia’s transportation emissions. Likewise, the nascent domestic renewable energy industry needs support to scale, and other industrial concerns in the country need to increase their energy efficiency to be competitive in the global market.

3. Scale social forestry

By empowering local communities to manage and use their forest resources, social forestry has been shown to reduce illegal logging practices and forest fires from slash-and-burn agriculture. Agroforestry and other sustainable utilizations of the forest can provide jobs for smallholders while maintaining carbon stocks through responsible forest management. The expansion of government initiatives to provide community assistance is an opportunity to increase the benefits from the social forestry program in Indonesia.

4. Promote energy-efficient buildings and appliances

Indonesia is one of the world’s great untapped markets for energy efficiency. For the most part, standards and codes regulating the energy use of buildings and appliances are well behind global and regional best practices. Developing and implementing more stringent standards and incentivizing energy efficiency retrofits would enable a wide array of benefits to Indonesian households, including lower energy consumption costs, better indoor air quality and improved thermal comfort. Benefits would also accrue to society at large from lowering peak electricity demand (limiting the need to build more power plants) and wide-scale job creation for energy entrepreneurs and trade workers (construction, electricians, installation, etc.).

5. Ensure quality electricity access

While over 95% of Indonesians have some access to electricity, ensuring quality access will improve the health and economic opportunities of Indonesians while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The state-run electrification program often uses diesel generators to provide electricity in rural areas, which is highly polluting to local air as well as unreliable and expensive. Replacing diesel generators with distributed renewable energy will result in immediate health benefits while, over time, quality and sustainable electricity access can help power economic activity in rural areas where poverty rates are disproportionately high.

Conclusion

From electrifying transportation to the development of social forestry and low-carbon industries, there are many opportunities that can help Indonesia recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, achieve its development priorities, and improve the health of local communities while delivering significant climate co-benefits. Instead of locking in a future with high-carbon infrastructure, stranded assets, and deadly air pollution, Indonesia still has the opportunity to choose another path — one that combines low-carbon economic opportunities with clean air and climate protection.

We’re excited to share our new brief tracking philanthropic funding for climate change mitigation, Funding trends: Climate change mitigation philanthropy. This latest ClimateWorks Global Intelligence research offers a glimpse into the unique datasets that we combine with our in-house expertise and global partnerships, to provide insights and guidance on top areas for climate action and philanthropic strategies.

We’re excited to share our new brief tracking philanthropic funding for climate change mitigation, Funding trends: Climate change mitigation philanthropy. This latest ClimateWorks Global Intelligence research offers a glimpse into the unique datasets that we combine with our in-house expertise and global partnerships, to provide insights and guidance on top areas for climate action and philanthropic strategies.

We sat down with Surabi Menon, Vice President of Global Intelligence, to learn more about funding trends for climate change mitigation philanthropy and why it is important to track these numbers.

What is important about this brief?

This research, led by Hannah Roeyer, a long-time staff member and now consultant, brings together data on foundation and individual climate change mitigation funding to explore giving across a set of sectors and regions. It offers many important findings for those focused on climate philanthropy. First, it provides an estimate of total philanthropic funding for climate change mitigation. It dives deep into foundation funding and shows exactly where that funding is going, both by geography and sector. It also highlights some ways of thinking about gaps and opportunities that philanthropists might consider as they look to direct their giving to address the climate crisis most effectively.

What are some of the key funding trends in climate change mitigation philanthropy?

Overall, we were encouraged to find that total foundation funding to climate change mitigation, one component of the climate mitigation philanthropy picture, nearly doubled since 2015.

Overall, we were encouraged to find that total foundation funding to climate change mitigation, one component of the climate mitigation philanthropy picture, nearly doubled since 2015.

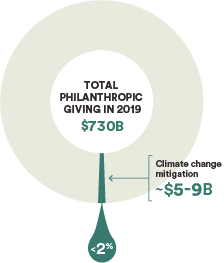

In 2019, philanthropic funding to climate change mitigation across both foundations and individuals was $5 billion to $9 billion. However, this represents less than 2% of total philanthropic giving around the world — across individuals and foundations.

We also identified several sectors where funding levels do not match the need. For example, our brief shows that the industrial and building sectors collectively receive less than 8% of foundation funding while accounting for 26% of direct emissions reductions needed to meet international climate goals under the Paris Agreement. Therefore, those are great areas for philanthropic funders to consider filling the gap as they develop investment strategies.

What is the ideal amount of funding for climate change mitigation?

Trillions of dollars in investment are needed from public and private sectors, and philanthropic investments can help create the leverage needed to do it. While there is not a specific goal for philanthropic funding needed to fight climate change, we know significantly more philanthropic resources can be deployed effectively over the coming years to tackle this existential threat.

How can this information be used to inform broader climate change mitigation efforts?

The Funding Trends report is designed as a companion piece to our recent Global Intelligence report, Achieving global climate goals by 2050. Published last month, this report highlights seven sectors across 10 geographies where the world can target large-scale emissions reduction opportunities to meet global climate goals. Our intent with both of these reports is to provide the absolute best research and analysis to enable climate funders to optimize their giving and most effectively combat the climate crisis.

Identifying gaps in funding enables philanthropy to support critical areas of need. For instance, while the world is trying to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century, total emissions across Africa are projected to increase by over 2.5 times by 2050, based on a reference scenario. Although climate adaptation will continue to be a focus across the continent, these projections indicate that mitigation is increasingly important. However, over the past five years, Africa has received less than 4% of global foundation funding for climate change mitigation. Climate philanthropy can catalyze financing to support mitigation efforts that can boost economic and social development. There are many options available that are addressed in the report.

What inspired ClimateWorks to develop this report?

We regularly provide this data to our partners to help inform their investment strategies. We’re excited to make this data more broadly available to increase awareness of climate change mitigation gaps and opportunities. We also want to highlight the important role of philanthropy in catalyzing change. We are inspired by the many climate commitments being made by new donors. We look forward to engaging with new partners as we update and share these numbers on an annual basis going forth.

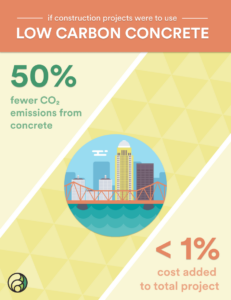

Buy Clean is one of the most popular policy ideas currently being discussed to reduce industrial greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

It is a family of policies that use government purchasing to create markets and incentives for building materials manufactured with lower GHG emissions. In this post, I want to unpack what’s at stake in Buy Clean policies—both financially and for the planet—and show why they are such a powerful tool. We can dramatically reduce emissions with hardly any increase in the cost of public construction projects.

Why do we need Buy Clean ?

?

Industrial production has one of the highest GHG emissions of any sector of the economy, and almost half of direct industrial emissions come from making building materials.[footnote tooltip=”https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/overview.php?v=booklet2019″][/footnote] These include almost all cement, more than half of all steel, and about a fifth of plastics.[footnote tooltip=”http://withbotheyesopen.com/index.html, https://materialeconomics.com/publications/the-circular-economy”][/footnote] The Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction estimates that more than 10% of all carbon dioxide emissions come from producing building materials,[footnote tooltip=”https://www.worldgbc.org/sites/default/files/2018%20GlobalABC%20Global%20Status%20Report.pdf”][/footnote] which often end up in public construction projects like roads, electricity transmission lines, water works, and public buildings. Because governments are among the largest purchasers of these climate-polluting industrial materials, establishing clean government procurement processes can have an outsized impact in protecting the global climate.

An Example: U.S. Federal Infrastructure Funding

The stakes are clear when we look at a recent legislative proposal in the U.S. Congress, which would invest about $1.5 trillion in transportation, water, education, communication, and energy infrastructure.[footnote tooltip=”https://transportation.house.gov/news/press-releases/house-democrats-release-text-of-hr-2-a-transformational-infrastructure-bill-to-create-jobs-and-rebuild-america”][/footnote] Of that, about $1 trillion is allocated to construction. This bill did not include any Buy Clean provisions, so it’s useful to estimate what this bill would mean for futureGHG emissions. For simplicity, I’ll focus on cement, but similar estimates can be made about other building materials.

To estimate how much cement is needed for $1 trillion of public works, we can look at how much cement was used in past public construction. Over the last five years, the U.S. has done about $300 billion per year of public construction.[footnote tooltip=”U.S. Census Bureau. Value of Construction Put in Place. Tech. rep. CB20-48. Economic Indicator Division, Construction Expenditures Branch, 2020. URL: https://www.census. gov/construction/c30/c30index.html.”][/footnote] Across the economy, the U.S. uses about 100 million tons of cement per year,[footnote tooltip=”The U.S. produces about 90 million tons of cement per year and imports a net of 10-15 million tons per year. USGS. “Historical Statistics for Mineral and Material Commodities in the United States”. In: ed. by T. D. Kelly and G. R. Matos. USGS Data Series 140. U.S. Geological Survey, 2016. Chap. Cement Statistics. URL: https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/historical- statistics/. U.S. International Trade Commission. USITC DataW eb: HS2523 (Portland Cement) statistics. Tech. rep. 2020. URL: https://dataweb.usitc.gov/.”][/footnote] of which just under half goes to public construction, paid with taxpayer dollars.[footnote tooltip=”PCA. U.S. Cement Industry Annual Yearbook. Tech. rep. Portland Cement Association, 2017. Table 11.”][/footnote] That means for every billion dollars we spend on public construction, we need 0.15 million tons of cement. An investment of $1 trillion in public works would therefore need 150 million tons of cement, generating 130 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions.[footnote tooltip=”https://gccassociation.org/gnr/United States/GNR-Indicator_59cAG-United States.html”][/footnote] In other words, the cement needed to implement this single piece of legislation would generate as much carbon dioxide as a state as large as Georgia or New York generates in a year.[footnote tooltip=”https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/state/”][/footnote] If we include all building materials, implementing this law could generate as much as 200 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions. Clearly, Buy Clean provisions are needed to ensure that public works initiatives don’t do lasting harm to the planet.

The Cost of Buy Clean

A logical next question is whether clean government procurement is affordable. Yes, it is. Cement costs about $100 per ton, meaning it accounts for only 1.5% of the cost of public construction on average.[footnote tooltip=”Construction costs cited above exclude land acquisition costs and a number of other factors, so cement is probably less than 1% of total project cost.”][/footnote] Many interventions that reduce cement GHG emissions are low- or even no-cost, like increasing the use of clinker substitutes.[footnote tooltip=”https://www.lc3.ch/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/2016-UNEP-Report-Complete6.pdf”][/footnote] However, because cement is such a small portion of the total cost, even emissions reductions that are generally considered prohibitively expensive would hardly affect the cost of an infrastructure project. For example, electrifying a cement kiln would cost about $50 per ton of cement, at typical electricity prices.[footnote tooltip=”Additional energy cost, assuming 7 cents per kWh industrial tariff.”][/footnote] That would eliminate half of the carbon dioxide emissions and add less than 1% to the cost of a typical project. Retrofitting an existing kiln to capture and store the carbon dioxide emissions could add as little as $60 per ton of cement[footnote tooltip=”P. Bains, P. Psarras, and J. Wilcox. CO2 Capture from the Industry Sector. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 63:146–172, 2017.”][/footnote] and eliminate nearly all carbon dioxide emissions, again at a cost of less than 1% of the total project cost.

Ultimately, Buy Clean requirements will not add significantly to the cost of public works because material costs are not a major driver of project costs. Labor, financing, equipment, insurance, design, and engineering — all of these things cost much more than structural materials.

Simply put, we can afford to use clean materials. Buy Clean can significantly reduce climate-changing emissions at very low cost. It’s a powerful tool, and we should use it much more aggressively.