We are excited to announce the Drive Electric Campaign, a global effort to achieve 100% electric road transportation for the benefit of the climate, health and justice, and the economy.

Today’s combustion-based transportation system is inequitable, expensive, and contributes to enormous costs to the climate and our health.

The Drive Electric Campaign believes that a better future is possible. The rapid transition to electric vehicles (EVs) of all types — cars, vans, trucks, buses, and two- and three-wheelers, and e-bikes — can eliminate billions of tons of harmful emissions, save hundreds of thousands of lives per year, and prevent millions of cases of respiratory disease caused by pollution from combustion vehicles.

EVs also help the economy by creating opportunities for new investments and jobs in manufacturing and infrastructure — saving people money on fuel and maintenance, reducing oil demand that distorts geopolitics and the balance of trade, enabling greater renewable power generation, and avoiding trillions of dollars of climate-related damages linked to the burning of fossil fuels. Simply put, the electrification of road transportation vehicles is one of the most powerful, globally scalable solutions we have available now to achieve climate objectives while delivering a more equitable and just transportation system.

We know there is still a long way to go before we reach 100%. We are also increasingly confident we can win. Recent progress, supported by our partners, has created unprecedented momentum.

For example, over 100 national, state, and city governments representing nearly one-fifth of global transport demand have committed to 100% emission-free transport. They are banding together through initiatives like the International ZEV Alliance, Green and Healthy Streets, Global Drive 2 Zero, the Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Transition Council, the ZEV Community, and many others to pursue joint action on regulations and incentives to accelerate EV supply, demand, and infrastructure.

The private sector is stepping up as well. Vehicle manufacturers are investing hundreds of billions of dollars to bring new EV products to market and making commitments to shift to 100% zero-emission vehicle production by 2035 or earlier. Utilities are investing to enable charging infrastructure that can improve the integration of renewable power generation and provide benefits for all utility customers. Over 100 companies representing a fleet of over 4.8 million vehicles have committed to 100% electrification by 2030, including Baidu, DHL, Lyft, Leaseplan, IKEA, Ryder, Swiss Post, and the State Bank of India, among others.

Bigger, more powerful, and more diverse people-powered coalitions representing health, environment, business, labor, and frontline communities are banding together to demand stronger regulations and a better future. It’s working. In many countries, especially those with strong policy support, EV sales are trending rapidly upward even during the pandemic. With a sustained and concerted global effort, a tipping point is within reach as soon as 2025, when EVs could outcompete combustion vehicles on price, convenience, and performance.

Still, a complete transition at the speed and scale needed to save the climate is neither easy, nor inevitable. Those invested in the status quo are increasing their opposition and the risk is that, if we continue with business as usual or fall prey to the forces of inaction, the vast majority of vehicles will still run on polluting fossil fuels in 30 years, with dire consequences for the climate, public health, and the economy. As the world faces a decisive decade to put us on the path to a stable climate, now is the time to build on current momentum and pursue a bold campaign to overcome the remaining barriers and secure the path to a 100% zero-emission road transportation future.

Achieving this promising future requires systems change on a global scale. The Drive Electric Campaign collaborates with a diverse set of partners, including NGOs, foundations, and coalitions representing key stakeholders from government, business, and civil society, and focuses on three interconnected strategies:

- Supporting smart government policies that overcome barriers and grow the EV market, such as emission standards and EV sales targets for automakers, purchase incentives for consumers, public EV procurement, and many others.

- Encouraging business leadership and engagement such as by electrifying their fleets, supporting their employees and customers to adopt EVs, mobilizing finance and investors, engaging vehicle manufacturers to commit to a transition toward 100% zero-emission vehicle production, and increasing coordinated action and business support for key government policies.

- Engaging people power to drive transformative change by supporting diverse organizations and coalitions representing health, environment, labor, consumers, and business, and elevating the voices of communities affected by transportation pollution.

By working in partnership, the campaign takes a systems approach to secure commitments and actions that will put us on the path toward all new vehicle sales to be zero-emission by:

- 2030 for city and school buses and two- and three-wheelers;

- 2035 for passenger vehicles; and

- 2040 for freight trucks.

The end of polluting road transportation is within sight. But whether it happens in time to save the climate and fully realize the large potential social benefits depends on the actions we take together today. We invite you all to be a part of this movement to deliver a better future for our climate, health, and economy. To find out more, visit the Drive Electric Campaign website, which will be a hub for the campaign’s activities, highlighting the accomplishments of our partners and the growing momentum toward a 100% zero-emission road transportation future. This initial landing page launched today is just a start, and will expand over time. Sign up and join us for this journey.

3 others

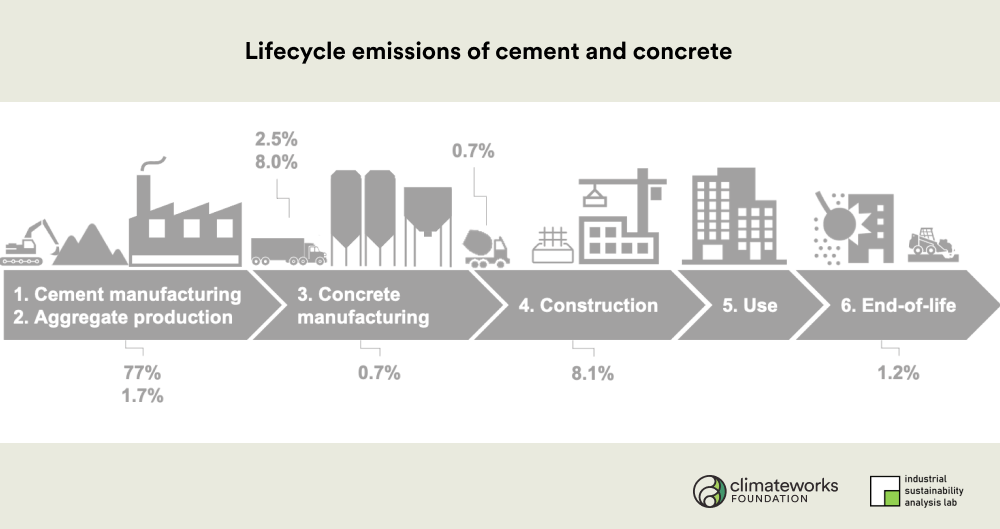

Why focus on infrastructure

Concrete is the world’s most used building material, and demand for it continues to rise globally. As the world rapidly approaches 1.5° C of warming, the cement and concrete cycle, which represents roughly one-tenth of the global total greenhouse gas emissions, cannot continue business as usual. A cradle-to-cradle decarbonization pathway in this sector is particularly important today, as the U.S. Congress is considering a new infrastructure bill as part of the Biden administration’s “Build Back Better” agenda. According to new research from Northwestern University, supported by ClimateWorks Foundation, there is an opportunity to align that rebuilding with domestic and international climate goals.

The new report, “Decarbonizing concrete: Deep decarbonization pathways for the cement and concrete cycle in the United States, India, and China,” shows in greater detail than ever before that there are multiple pathways to get the cement and concrete industry to net-zero emissions by midcentury by ramping up conventional mitigation approaches, increasing research and development, and reducing demand through measures like lean construction and substituting engineered timber building materials for concrete. Governments and companies equipped with this system-wide understanding can set more ambitious targets for economy-wide decarbonization.

What decarbonizing cement by mid-century would look like

One clear conclusion of the report is that there is no single solution, but rather a range of changes that will be necessary. The report identifies three categories of decarbonization, which is then broken down into seven approaches and 30 specific levers.

Some of these approaches are technologically mature and exist at the commercial scale, such as improving energy efficiency at cement plants and certain carbon utilization technologies. Others exist at pilot-scale and require more research and investments to improve cost and performance, such as lower-carbon cement chemistries. Options like using materials more efficiently and substituting timber engineered for greater strength and fire-resistance for concrete requires more consumer awareness and widespread availability.

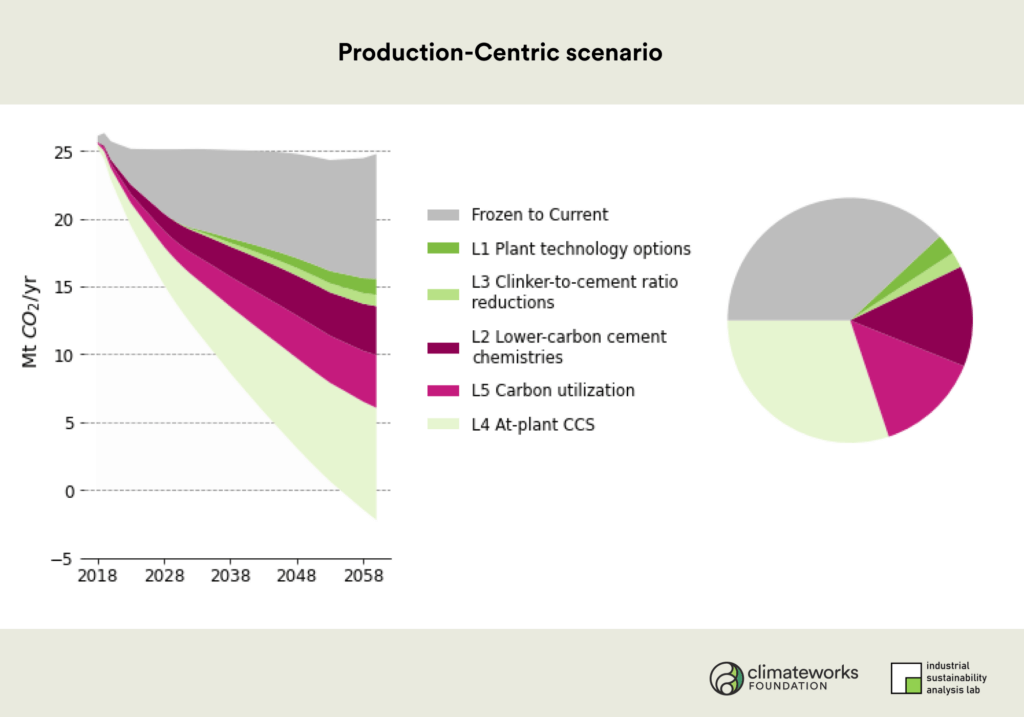

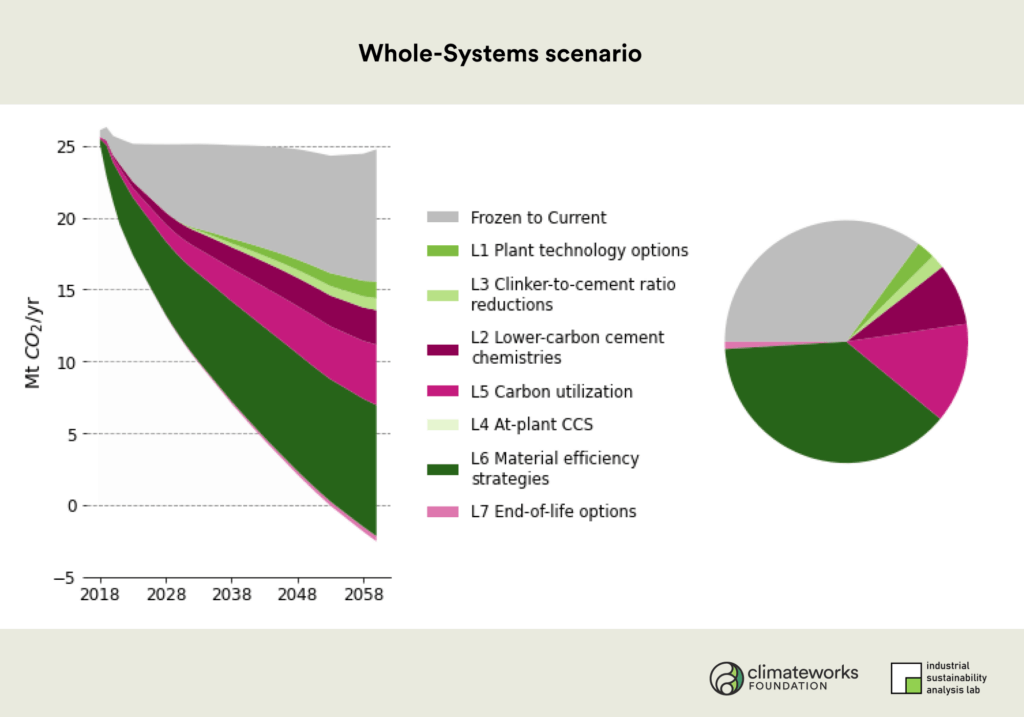

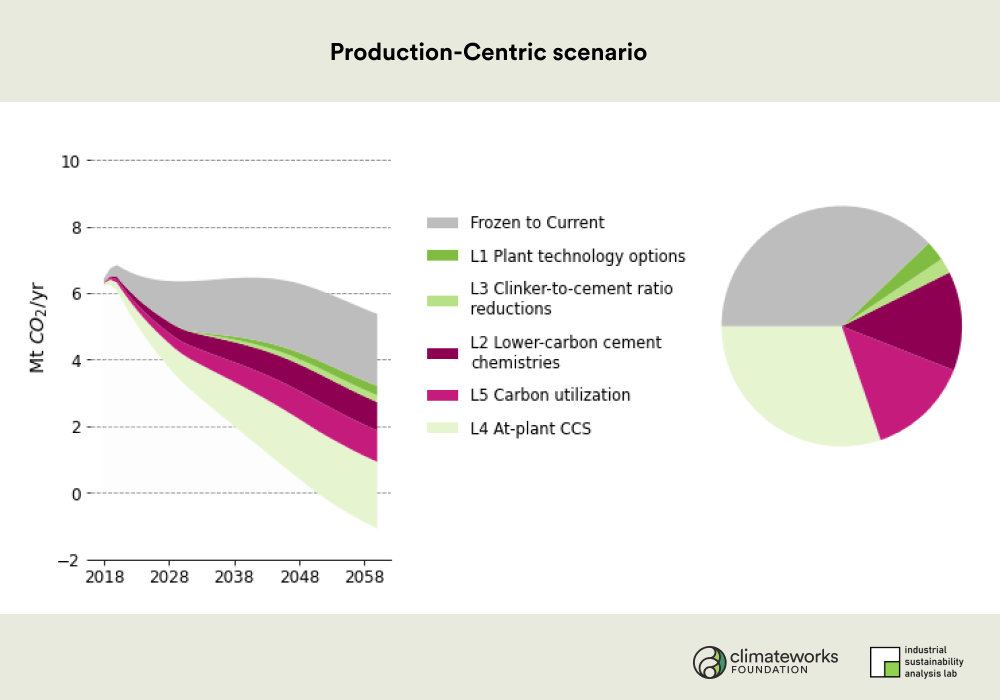

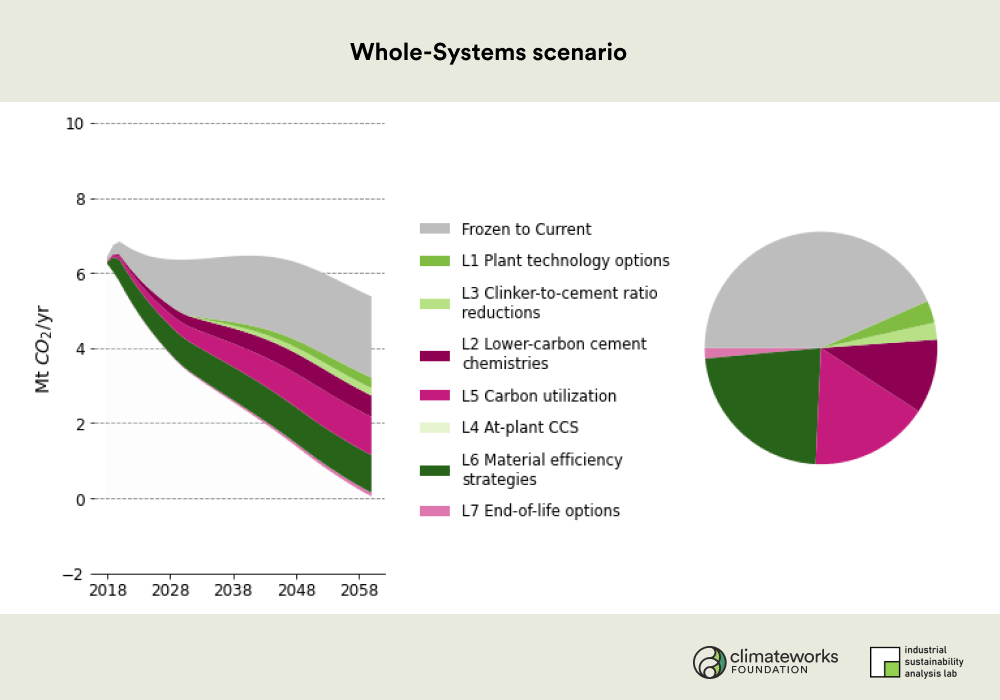

The research examines two plausible scenarios of how to decarbonize cement and concrete across its entire life cycle. The Production-Centric scenario explores ways to reach net-zero emissions solely through measures that reduce the carbon intensity of cement and concrete production. This is in line with the traditional business models and thus relies on action taken primarily by the cement and concrete industries. This scenario shows that technological improvements to cement and concrete manufacturing processes can dramatically decrease the carbon intensity of cement through the use of lower-carbon cement chemistries, switching to cleaner energy sources, capturing CO2 emissions at the plant, and storing CO2 in the cement and concrete. However, some of these options may increase the cost of cement and concrete considerably and some require additional research and development in order to improve commercial viability.

The alternative Whole-Systems scenario explores a wider portfolio of levers, with emphasis on reducing demand for cement and concrete. This scenario still requires a substantial amount of technological improvement, along with actions by a broad array of stakeholders to use cement and concrete much more efficiently. The CO2 emission savings come from the combined effects of lower production emissions, reduced concrete demand, and CO2 stored in building materials. The challenge here is the need to embrace new business models, the need for rapid development of enabling policy regimes, and the need to mobilize a larger group of stakeholders from architects to the general public.

Decarbonization potential of concrete in U.S. buildings across seven levers

Decarbonization potential of concrete in U.S. roads across seven levers

Everybody has a part to play

Policymakers can make these pathways possible by increasing investments in R&D, providing technology deployment incentives, changing construction codes and standards, and encouraging public-private partnerships to develop, demonstrate, and deploy key technology innovations. Governments can also use public procurement to create markets for both low-emissions concrete and concrete alternatives through policies like Buy Clean.

Philanthropy can also play a key role. It can support groups that inform policymakers about the policy options available. It can help catalyze the use of low-emissions alternatives in the private sector by creating consumer awareness and voluntary certifications for sustainable building materials. It can generate case studies and knowledge-sharing networks to reduce perceived risk and accelerate best practices in design and built environment policies, and develop targeted roadmaps. New databases on markets, as well as the costs and savings of various initiatives, can help chart the course at the country level.

The public and private sectors need to get serious about decarbonizing the cement and concrete cycle now — there is no time to waste. Different countries will encounter different challenges and opportunities. Countries with established stocks of buildings and infrastructure, like the U.S., will use different combinations of approaches than countries like India that still need to build out their stock. This research has shown that we have enough tools to meet these challenges, and we need to get started now. Governments should feel confident setting ambitious, long-term net-zero emissions targets, and should implement them through near-term action. In the U.S., federal procurement standards and other supports for concrete and cement cycle decarbonization in the upcoming infrastructure bill, as well as its updated Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement, are important opportunities to take the first steps down this path.

Learn more

Read the full report here, or contact us to learn more about how to decarbonize the cement and concrete industry.

Over the past year, ClimateWorks has supported a program in Kenya that eventually led the country to include super pollutants emissions reductions in its 2020 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) for the first time.

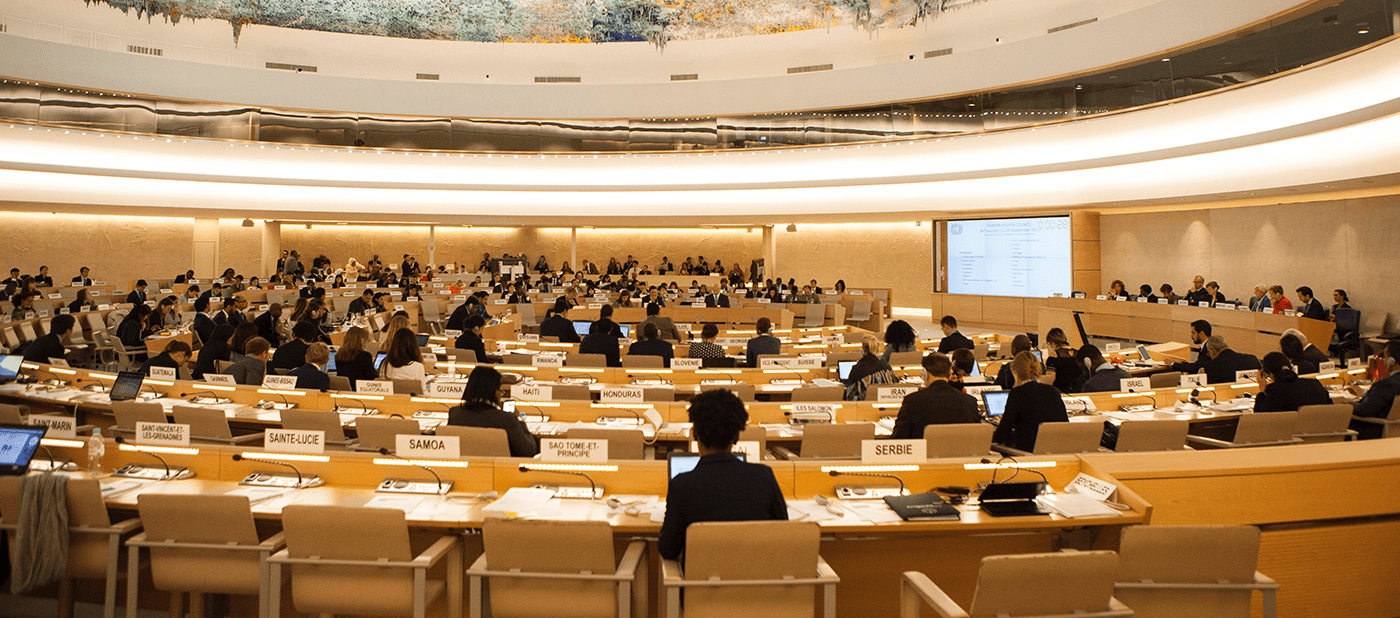

Reducing emissions of super pollutant greenhouse gases that are thousands of times more damaging to the climate than carbon dioxide is the only way to slow the pace of global warming before 2050. Eliminating such super pollutant emissions, including methane, hydrofluorocarbons used as refrigerants, and black carbon from diesel consumption and burning biomass, also reduces human exposure to dangerous levels of air pollution. Over the past year, ClimateWorks has supported a program in Kenya to achieve both of these outcomes, eventually leading Kenya to include super pollutants emissions reductions in its 2020 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement for the first time. That revised NDC showed marked improvements in ambition and funding support for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Kenya took great strides to be listed among the 39 nations that submitted their updated NDCs in 2020, the deadline set out by the Paris Agreement. This is a laudable demonstration of climate ambition for a nation whose per capita greenhouse gas emissions are nearly 60% below the global average.

The newly updated NDC includes some significant changes that will strengthen Kenya’s response to the climate crisis.

- Kenya has increased its emissions reduction target from 30% to 32% by 2030 below the baseline of 143Mt of CO2 eq (excluding land and land-use change).

- While the previous NDC was fully conditional on international financial support, Kenya is pledging over US$8 billion from the national budget toward implementing the new plan, or about 13% of the estimated total cost.

- It has now included super pollutant mitigation in its enhanced NDC plans, which represents a significant win for both the climate and human health.

During the multi-stakeholder NDC review process that led to the enhancement of the NDC, ClimateWorks grantees Joyful Women organization, Kenya Meteorological Society, and affiliates from the Kenya Council of Governors, and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, engaged the Ministry of Environment, civil society, and county executive committee members to present data and information on the extent of super pollutant emissions, and to examine legal and policy strategies to reduce them. This led to heightened national awareness on the climate and health impacts of these harmful pollutants.

The timeliness of Kenya’s new commitment cannot be overstated, as the country’s super pollutant emissions are projected to rise by 2050 due to changing socio-economic conditions. In particular, the updated NDC recognizes the unique challenges presented by the widespread use of biomass to meet household energy needs, and notes that a significant proportion of the US$62 billion needed to implement the NDC will have to go toward addressing the nation’s rising energy demand. This includes investing in green energy infrastructure that will enable a sustainable and just transition away from planned coal-based electricity generation.

The enhanced NDC sends strong signals of commitment to multilateral climate action from East Africa’s fastest-growing economy, even as it struggles to balance a mounting public debt burden of US $66 billion. It is perhaps this dual challenge that has pushed the government to include mechanisms such as debt-for-climate swaps as one of the financing mechanisms for the updated NDC.

It remains to be seen whether the promise of a debt-for-climate swap can deliver super pollutant emissions reductions. However, an approach that focuses on delivering multiple benefits and sustainably developing Kenya’s economy as enshrined in Vision 2030 – the nation’s development blueprint – can provide opportunities to rapidly reduce super pollutant emissions. It will also strengthen the nation’s adaptive capacity to better manage the impacts of climate change across sensitive sectors of the economy.

The results of the consortium study will be published in the third quarter of 2021 and are planned for public release at the UNFCCC 26th session of the Conference of the Parties in Glasgow.

We sat down with Liz McKeon, head of the climate action portfolio at IKEA Foundation, to discuss their climate journey and how ClimateWorks helped scale their impact.

When Liz McKeon joined the IKEA Foundation[1] in 2014, the organization‘s climate giving strategy was just taking root. In the years following, Liz has worked to scale funding climate related programs from $1.5M to $36M to cover a wide range of solutions and geographies. After the foundation officially established its Climate Action portfolio in 2018, Liz began building a team with two colleagues joining in 2019 and one more recruitment on the way.

We sat down with Liz (virtually, of course!) to discuss IKEA Foundation’s climate journey and how ClimateWorks helped scale their impact.

___

______

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Why are you passionate about climate and what guides you in this work?

I am an American living in Europe and have been in and out of philanthropy since 1992, when I started my first job with the McArthur Foundation. I’m a bit of a square peg in the climate realm since I’m not a climate expert and haven’t been in the field from the beginning. You could call me a Sovietologist by training — I spent many years working in the Soviet Union, and then (post-collapse) in Russia.

My professional life has focused on issues that are essentially about the changing nature of the political economy and personal behavior, two themes that are so relevant to the climate challenge now! I also did a teaching assignment in apartheid in South Africa, which helped me understand structural inequality, and now motivates me to tackle the climate challenge from that angle as well.

Tell us about the IKEA Foundation’s journey into climate philanthropy.

It’s an interesting story. The foundation was set-up as a children’s foundation in the 1980s and started out in earnest in 2009. The climate impetus was a stroke of leadership coming from our board. The sons of IKEA’s founder, Ingvar Kamprad, understood the reality that we are not going to survive if we don’t take care of the planet. They also deeply believe that responsible businesses can lead the way in driving solutions.

In 2014, the foundation pledged to put businesses at the forefront of fighting climate change by launching We Mean Business, a coalition of organizations that advise companies on ways they can become more sustainable and responsible. I joined soon after that decision was made. Setting up the We Mean Business coalition and helping them launch was one of my first tasks.

It wasn’t until 2018 that we were able to reorganize the strategy and rethink how we can still hold true to our value of making the world better for kids while also focusing on other issues.

We focused on two strategies: protecting the planet and helping families afford a better everyday life.

That was the beginning of a new portfolio structure for the IKEA Foundation and we’ve been ramping up our climate giving ever since.

What were some of the projects that you were working on before you started collaborating with ClimateWorks?

Our climate commitment started in 2014 with the creation of the We Mean Business coalition. We also recognized the need for broad-based public mobilization early on, so our initial funding was also geared to launch something called the Here Now campaign. This later became the Purpose Climate Lab, whose work is centered around building momentum for change and accelerating climate solutions through advocacy and partnerships.

Tell us about your involvement with ClimateWorks. How were you able to build and grow your giving strategy with us?

Having a non-climate background, one of the first needs I had was to overcome the intellectual challenge of getting up to speed. With ClimateWorks as a partner, I was able to access a vast network of funders and knowledge in order to understand the field quickly — where the funders were in their thinking and approach, and the opportunities and barriers of different solutions. When you’re a small team, you can’t imagine how important it is to get that knowledge quickly to scale your work.

Once the IKEA Foundation’s climate grantmaking work kicked off, I also began to understand that with ClimateWorks, not only can you pinpoint where you can make the most change through their Global Intelligence services, but they will also partner with you in the evolution of your own giving strategy, as well as involve you in the development of their grantmaking programs.

For instance, our Indonesia work started with mapping out mitigation opportunities and is now evolving to the next phase of action, where we need a ready set of grantees and a coordinated funder effort in the region. ClimateWorks is organizing and leading us on both those fronts.

With a small staff, we also knew we couldn’t engage in the transaction cost of giving small grants to the many organizations that are implementing solutions we need across the globe. We needed a partner like ClimateWorks that could build the grantee field and distribute the funds to the most effective groups. So, the ability of ClimateWorks to channel funds to multiple grantees and projects was really helpful.

What are some solutions you’re working on with us?

In our first round of grants, we funded ClimateWorks’ Transportation program, which is working globally to tip the scales on the adoption of electric vehicles. We are also a leading partner in the project to identify opportunities for climate change mitigation philanthropy in Indonesia, a leading country in a region that hasn’t been a focus for philanthropy.

ClimateWorks Global Intelligence is another area we support. By providing insights on both climate change and philanthropic funding, it is helping the funder community act more efficiently and quickly when opportunities arise.

In our second round of grants, we started working closely with the ClimateWorks Finance program and are funding initiatives to shift capital away from fossil-based investments toward more sustainable, green investments.

The climate crisis is upon us in no uncertain terms. What do you think philanthropy can do to avoid the worst impacts of climate change?

I feel incredible impatience when it comes to the climate crisis. Everything that needs to happen should’ve been done yesterday. We are way behind where we need to be. But I do believe that this is a crisis we can overcome. Climate is a fast-paced, fast-moving, and a highly politicized area of social progress, so it needs leadership and consistency, both of which philanthropy can provide.

For instance, I saw early on how we were able to collectively show up at Paris in 2015 to help move the agenda and secure what were some real wins in the Paris Agreement.

I’ve also seen how philanthropy can step in and unite different groups on climate action. The We Mean Business coalition, Purpose Climate Lab, and the Clean Air Fund are great examples of how philanthropy can bring together groups that matter so much to the changes that need to happen at a systematic level.

Sometimes philanthropy is also able to capitalize on a brilliant moment that will not happen again. Europe’s Green New Deal is on the table now and we need to opportunistically move with the speed of that moment and make sure we make the best of it.

What advice would you give to a new funder thinking of climate?

Talk to ClimateWorks. They have so many relationships and act as the gravitational pull for the community through the data, the reporting, and the conversations that they coordinate across many different regions and subject areas. Not to trivialize it by calling ClimateWorks a “fast pass,” but when you are in earnest trying to get a sense of where fellow funders are, where issues stand, and how to deliver the best possible contribution you can make as a single philanthropy, collaboration takes center stage. And ClimateWorks is one of the groups that really brings that collaboration in living form to the table every day.

[1] IKEA Foundation is the philanthropic arm of INGKA Foundation.

We applaud the Biden administration for the historic, bold steps it announced today to tackle the climate crisis with the urgency it deserves and the government-wide action it needs. In taking a science-driven policy approach — one that puts job creation and environmental justice at its center — President Biden is putting the U.S. on a path toward long-term sustainable and equitable economic recovery.

The administration’s substantive, coordinated leadership to re-engage the U.S. on climate comes at a critical time and includes significant commitments, such as the intent to ratify the worldwide Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, develop a national finance climate plan, and procure zero-emission vehicles for government fleets. The administration also is rightfully centering its commitments on racial, social, and economic justice, which includes developing recommendations to direct federal investments so that 40% of the overall benefits flow to marginalized communities. These are just some of the important actions revealed in today’s announcement.

This is the decisive decade to take transformative action to keep global temperature rise below 1.5° C and avoid the worst impacts of a warming world. The wide-ranging actions by this administration reflect an understanding that we simply don’t have time to delay, and, frankly, that the U.S. needs to make up for a significant amount of lost ground from the past four years.

It’s invigorating to begin this year with such meaningful action on climate from the U.S. 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic, its economic impacts, and movements for social and racial justice, laid bare our global interdependence. It also revealed the possibilities of what can be achieved when we recognize and appreciate the interconnected nature of the challenges we face and work together to pursue solutions aimed at creating a more just and healthy future for all people.

ClimateWorks believes deeply that when ambition, collaboration, and action come together, there is no problem too big to solve, including climate change. Today’s announcement from the Biden administration, coupled with last week’s Day One climate actions, possess these key ingredients, and will help push our world closer to ending the climate crisis. Much work remains to be done, but it is important to celebrate progress when it is being made. Today, progress was made.

It has been an exciting and eventful week all around for climate advocates.

From the U.S. rejoining the Paris Agreement to the raise of $1B for investments in climate innovation, the momentum to turn climate pledges into action is accelerating.

One climate solution attracting increased attention is carbon dioxide removal (CDR), which was recently profiled by the New York Times in a piece highlighting an uptick in businesses exploring CDR as a way to remove vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In a further sign of the private sector’s growing interest, Tesla CEO Elon Musk just promised a $100 million prize to spur development of the best CDR technology.

Also this week, the U.S. Department of Energy announced this year’s Secretary Honor Award recipients, which notably included a groundbreaking study on carbon removal. Led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and funded by ClimateWorks, the “Getting to Neutral” Carbon Emissions Team earned the award for its work on how California could reach the goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2045.

A first-of-its-kind study, “Getting to Neutral: Options for Negative Carbon Emissions in California,” examines a robust suite of technologies and their costs to help California become carbon neutral – and ultimately carbon negative – by 2045. The report identifies where to find carbon removal opportunities in the state, including the opportunity to couple direct air capture with low-carbon energy sources like geothermal heat.

At ClimateWorks, we are excited to see more attention paid to carbon removal. Both natural and engineered strategies are necessary to scale as part of the global effort to end the climate crisis. But it is also important to remember that removal is not a substitution for mitigation. Frankly, the world has waited too long to mitigate and now we have to do both if we are to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

However, there are critical challenges in carbon dioxide removal that must be addressed if an effective and socially equitable portfolio of CDR options are to be scaled. Indeed, while we are heartened by private sector announcements, we can’t ignore a common concern with carbon removal: the use of CDR technology by the fossil fuel industry to delay the transition toward zero emissions.

As CDR solutions are explored and implemented in the years to come, the technology cannot become a blank check for societies to continue with the same polluting behaviors that put us in the precarious position we are in today. There is tremendous opportunity for industry to use their infrastructure and their know-how to pull historic CO2 down from the sky and out of oceans and put it back in the ground. This would help to lead a just transition benefiting the health of all people and the planet.

We are nearly one year into the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite initial rollout of the much awaited Covid-19 vaccine, nations continue to struggle with containment of the pandemic, and many countries have reverted to some form of lockdown in anticipation of the approaching holiday season.

As we wrote earlier this year, Covid-19’s impact on the climate has yet to be written — but we now have a better idea of the near-term and long-term implications. Throughout the year, ClimateWorks has monitored a set of key climate-related indicators that have been affected by Covid-19. Here, we highlight significant Covid-19 impacts on key sectors and assess the implications for sustained climate action.

Will industry rebound?

At the beginning of the pandemic, we saw strict lockdowns cause sharp drops in industrial production in many countries. Today, the overall outcome is still a bit murky. In China, industrial output in 2020 is now outpacing 2019, and emissions from steelmaking in particular have risen in part due to government stimulus measures. China’s economy has benefited from its relative success in controlling its Covid-19 outbreak. However, the country’s public health success may be insufficient to revive its economy while major trading partners are still in recession. South Korea and Vietnam both fit this description and point to a continued suppression in industrial activity through the first half of 2021, at least until widespread vaccination occurs. In the long run, however, economic activity (and hence greenhouse gas emissions) will rebound, and the most consequential impact of the pandemic will be how historically large government stimulus measures will be spent.

Oil prices trend down, clean transportation trends up

After plunging in March and April, oil markets rebounded slightly in the third quarter of 2020. While consumption has risen from its lowest point, demand remains well below historical levels, and prices continue to stagnate at less than $50 per barrel. The CEOs of BP and Shell have warned that 2019 might represent peak oil demand and some even proclaimed the “end of the oil age.”

Low oil prices do not seem to be slowing the global momentum toward transportation electrification, as evident through the most recent news that Québec and the U.K. joined a growing number of governments accelerating the transition to 100% electric vehicles (EVs, including hybrids, plug-in hybrids, and full battery power). Europe took the lead in annual EV sales globally, driving forward efforts to catch up with China. Germany finally emerged as one of the continent’s hottest EV markets, and in the first seven months of 2020, Europe claimed the global EV sales lead by surpassing China’s EV sales by 14,000 units. Despite an overall plunge in new car sales in Europe, EV sales grew in percentage and absolute terms, accounting for 8% of all sales, double the market share compared to the same period in 2019. In July, EVs reached an all-time high of 18% of the total European passenger car market.

Lastly, the easing of Covid-19 restrictions led to a rebound in traffic congestion as a portion of public transit trips shifted to private vehicles due to safety concerns. This trend was also accompanied by a rise in shared and private micromobility (bicycles and e-scooters) trips, as well as a major uptick in bicycle sales across the U.S. and Europe.

Government response to the crisis

Governments around the world have passed a variety of fiscal stimulus measures meant to blunt the economic impact of the recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Some policy packages, such as the European Green Deal, have used this as an opportunity to build back better, making climate change mitigation one of the main priorities of their Covid-19 recovery. However, research by Vivid Economics has shown that of over $12 trillion spent in stimulus plans by 22 countries,18 of them are expected to have negative environmental impacts on net. Particularly egregious were the bailouts of airlines without any environmental conditions, a major missed opportunity and a demonstration of the lobbying power of incumbent industries at the expense of the low-carbon transition.

Sustaining emissions reductions after the pandemic

Global carbon dioxide emissions have been rising for five decades. 2020 will break that trend, with emissions projected to decline by around 7% or 8% relative to 2019 — but for all the wrong reasons. While Covid-19 has reduced economic production and personal mobility, and thus greenhouse gas emissions, we are already seeing emissions rebounds in countries that have gotten the pandemic relatively under control.

Going forward, we need to sustain a similar rate of emissions decline year over year for the rest of the decade to get back on track to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement, but analysts expect that emissions in 2021 will rebound. This should send a strong message that activity declines are insufficient to achieve a safe long-term climate. In order to move toward decarbonization in a post-pandemic world, we need to reduce the greenhouse gas intensity of human activities and begin to remove carbon from the atmosphere at scale in order to reach net-zero emissions by midcentury.

Implications of converging crises

In addition to a health and economic crisis of epic proportions, we are still hurtling towards temperature rise in excess of 3° C this century, which will likely have devastating consequences for people and the planet. While climate change and global health policy have largely been treated as separate issues by the public and media up to this point, the causes of both crises share commonalities, and their effects are converging. For example, we are seeing that the links between climate change, air pollution, and Covid-19 are at this point indisputable. A recent study showed that an increase of only one microgram per cubic meter in PM2.5 — fine particulate matter that is released in addition to greenhouse gases when burning fossil fuels — is associated with an 8% increase in the Covid-19 death rate. There is increasing evidence that both Covid-19 and the climate crisis disproportionately impact the poorest and most marginalized people in society, and both crises contribute to widening inequality.

The warming climate will play a bigger role in future pandemics, and moving forward, we must look toward more integrated solutions in responding to converging crises. According to the 2020 U.N. Environment Programme Gap Report, a low-carbon pandemic recovery could cut 25% of greenhouse gas emissions. Seizing this opening is critical to bridging the emissions gap. As we’ve seen, reductions in activity levels and energy consumption have resulted in real reductions in emissions. However, this is a solution that offers only short-term respite. Long-run deep decarbonization beyond the pandemic requires ambitious policies that drive emissions from our daily activities toward zero. Only then will we have a chance of meeting the Paris Agreement’s long-term goal of net-zero global greenhouse gas emissions by midcentury.

For more information on how ClimateWorks is responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, see here.

Ambitious airline commitments in direct air capture are needed but they must lead to clear reductions in the use of fossil fuels.

Aviation industry emissions are projected to triple by 2050, so returning to business as usual after Covid-19 recedes is simply not a viable option if the world is going to meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement. Aviation has lagged in making ambitious emissions reduction commitments. To be successful, the sector will need to rely on a variety of emission reduction approaches — curbing demand for flying, more efficient and novel new zero-carbon aircraft designs, a robust market for truly sustainable aviation fuels, and investments in carbon removal to address the remaining emissions.

Promising actions are happening. Recently, United Airlines announced an ambitious greenhouse gas reduction goal of 100% by 2050, and committed to doing so without voluntary offsets, or purchasing “credits” from projects that prevent or remove the equivalent amount of greenhouse gas emissions elsewhere. It also plans to invest in direct air capture (DAC) as part of this commitment.

Direct air capture removes historic carbon dioxide (CO2) pollution from the air. It is then stored permanently underground or used to create CO2-based products. In the case of United’s investment, the removed carbon dioxide will be used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) by injecting it into depleted oil wells to encourage oil production. The injected CO2 remains in the well and is stored permanently underground.

While United Airlines’ investment in permanent and verifiable emissions removal via direct air capture is a definite step in the right direction, it is important to differentiate this investment in DAC from the emissions reductions that might result from this investment. Instead of using removed CO2 for enhance oil recovery, better options to advance DAC and achieve higher climate benefits are available, such as reusing CO2 to create sustainable aviation fuel or storing carbon permanently without EOR. Scaling up these solutions requires further investments and support from the public and private sectors.

Unlike conventional offsets, direct air capture to storage offers permanent CO2 removal

Long-haul aviation creates residual emissions that are hard to mitigate because, unlike road transport, the sector lacks currently scalable clean technology alternatives. To date, the sector has relied mainly on offsetting, a problematic and limited solution to address its emissions. Combating these emissions requires meaningful actions to reduce fossil fuel use as well as permanently remove and store excess CO2.

Direct air capture removes historic emissions from the atmosphere and stores it underground, with an estimated 78% to 98% of injected CO2 remaining safely stored for the next 10,000 years. As a result, DAC offers a more impactful, long-term alternative to conventional offsets that face a variety of measurement, verification, and permanence issues.

Investment in or the procurement of direct air capture offer three major advantages for companies looking to address emissions from long-haul aviation:

- Compliance. By removing and permanently storing CO2 emissions, credits are generated for purchase by air airlines and other eligible procurers for emission compliance purposes.

- Decarbonization. Combining CO2 removed from the atmosphere with clean hydrogen creates carbon-neutral fuels usable by today’s aircraft and offers a viable pathway to decarbonize, rather than offset, carbon emissions from flights.

- Risk management. CO2 removed by direct air capture does not face the same reputational and climate risks associated with conventional offsets. Our recent blog discusses the distinction between carbon dioxide removal and conventional offsets in more detail.

…

Pairing direct air capture with synthetic fuel production can help decarbonize aviation

The climate benefit from United’s investment in direct air capture for enhanced oil recovery is unclear and depends on whether the oil produced will displace or add to existing production. The story is further complicated because, on one hand, revenue from selling CO2 for EOR increases demand for DAC, driving down costs and encouraging new project developments. On the other hand, the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change clearly states that in order to reach climate goals, we need to deploy carbon dioxide removal as well as reduce fossil fuel use. In addition to diminishing the overall climate benefit of DAC, EOR has received an ambiguous reception and even skepticism from local communities and environmental justice groups. Bundling an otherwise climate-beneficial technology such as direct air capture with EOR risks its social license.

Alternative pathways exist for businesses interested in investing in or procuring direct air capture. While direct air capture to storage without EOR would benefit the climate with less trade-offs, its high cost is unattractive to investors today. Absent strong policy signals, producing DAC-based fuels in lieu of fossil kerosene for fuel long-haul flights would both provide a revenue stream to scale direct air capture while at the same time eliminating the use of questionable conventional offsets.

After the purification process, captured CO2 is combined with green hydrogen through a chemical process powered by renewable energy to create synthetic kerosene. This fuel is compatible with today’s engines and because it’s simply a combination of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, early research reveals it has lower non-CO2 emissions than conventional fossil fuels as well. The production of this fuel takes up less land than crop-based fuels, and as a result, is less likely to compete with food production. With further research and development, including recent support from the U.S. federal government, this fuel can be carbon-neutral when produced using renewable energy, thus eliminating the need for offsets altogether and helping to create demand to scale direct air capture and green hydrogen industries globally.

Investment in direct air capture is a great start and should be emulated by other looking for near-term solutions to permanently address emissions from long-haul aviation. However, United needs to be crystal clear about the details — in particular how the investment will be directed, and how this investment fits into the airline’s overall plan to reduce its carbon footprint, since the airline has not committed to buying carbon removal. These details will be crucial to fully understanding the impact of this announcement and full transparency is critical to building trust and support with the public and policymakers.

On Paris Agreement’s fifth anniversary, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on the most notable climate achievements under the agreement to date, as well as important areas of focus for the next five years.

Five years ago this month, a landmark global agreement was reached to combat climate change. The Paris goals, which aim to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, are fundamental to maintaining human welfare. Already, we are becoming too familiar with the impacts of a changing climate — increased wildfires, melting glaciers, an ever-growing number of record-breaking weather events, and so forth.

Perhaps the most exciting takeaway from the last five years is that the global transition to a low carbon future is underway. The Paris Agreement set the foundation for countries to channel climate action in a coordinated way to maximize benefits for the health of people and the planet. But more needs to be done, and faster. The 2020s is the decisive decade for climate action and all efforts need to be greatly accelerated to put us on a path to achieve the Paris goals.

Another bright spot is the forthcoming re-engagement from the United States. The absence of leadership from the U.S. over the last four years was a significant setback but we’re optimistic about the action that will come under President-elect Biden’s administration. Certainly, the outcome of the Senate runoff elections in January will have a big influence on the pace of U.S. climate activity.

Here are notable achievements from the first five years of the Paris Agreement and key opportunities for further action:

Net-zero emissions moved from concept to commonplace

In 2015, net zero emissions targets were a concept. At the time, no country had committed to achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Today, not only is it a reality, it is commonplace. Nearly all the G7 countries and the G20 members have net-zero targets, including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, Argentina, Mexico, Japan, Canada, Republic of Korea, China, and the EU. However, the U.S. stands out for not having yet made a net-zero commitment.

In addition to the U.S. making its anticipated net-zero commitment, generally, the timelines for all commitments need to be ramped up. Additionally, we need more accountability and transparency by countries as they work to achieve their commitments.

Stronger climate plans from 151 countries and counting

Many countries have confirmed their intent to submit stronger climate plans by the end of this year. These plans, referred to as NDCs, can serve as templates for economic stimulus packages, guiding investments in the jobs, businesses, and clean air of the future. So far, a majority of these commitments have come from the more climate-vulnerable countries, such as the Marshall Islands, Jamaica, and Rwanda. Countries that emit large amounts of GHGs need to join these leaders and commit to stronger climate plans too.

Financing the climate transition

Having global financial systems aligned to support the low carbon economy transition is critical and important progress has been made. In the private sector, leading investors are now acknowledging climate change and climate policy. From the public sector, 150 national climate investment plans worth more than $25 trillion are expected in 2021.

Covid-related stimulus is a significant opportunity to align economic recovery with climate action to concurrently drive GDP growth and emissions reductions. Additionally, the divestment of fossil fuels must accelerate.

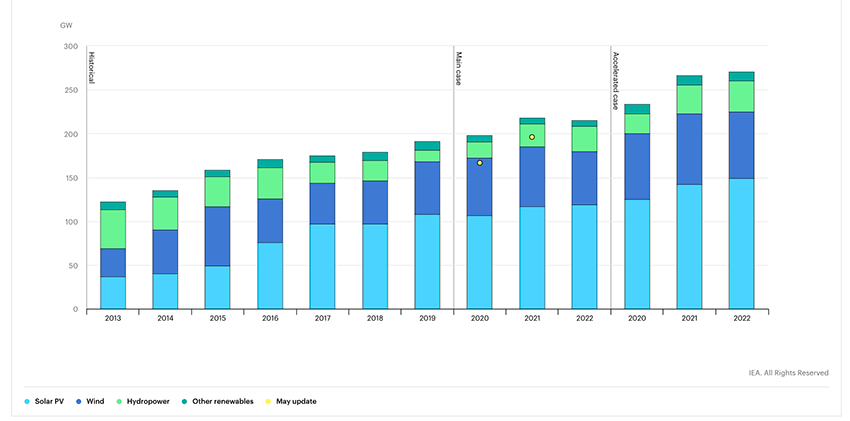

Exponential growth of renewable energy

The use of renewable sources of power has steadily grown since 2015 and renewables continue to displace fossil fuels. Renewable sources of power accounted for 26% of global electricity generated in 2015. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), renewables are poised for record expansion in 2021, with almost 218 GW becoming operational – a 10% increase from 2020.

Renewable electricity net capacity additions by technology, main and accelerated cases, 2013-2022

Looking ahead

Planned for November 2021, COP26, the annual UN Climate Change conference, will be a pivot point in the global climate framework — it’s when the final touches on the Paris Agreement should be done (e.g. Article 6), and new initiatives are incorporated, like sectoral approaches with non-state actors. Another important area to monitor closely is the global stocktake – an assessment of the world’s collective progress in meeting the Paris climate goals. The first global stocktake will take place in 2023 and will happen every five years thereafter. It will be an important mechanism through which we assess progress toward all of the goals of the Paris Agreement, including limiting emissions, adapting to climate change, and financing the transition, all in an equitable fashion.

This blog explores three key issues that are crucial to the success of scaling carbon removal strategies effectively and equitably.

The 2000s are often referred to as the “lost decade” of climate action. After many years without meaningful steps to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas pollution, the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C is slipping out of reach. In parallel, a growing number of companies and governments have announced ambitious pledges to achieve net-zero emissions that rely, in part, on carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

Interest CDR has never been higher, but successfully scaling an effective and socially equitable portfolio of CDR options requires a careful understanding of past problems and ongoing challenges. This post provides an overview of three key issues:

- variation in the permanence of carbon storage,

- accuracy in measuring real climate benefits, and

- concerns around the conflation of carbon dioxide removal with traditional carbon offsets.

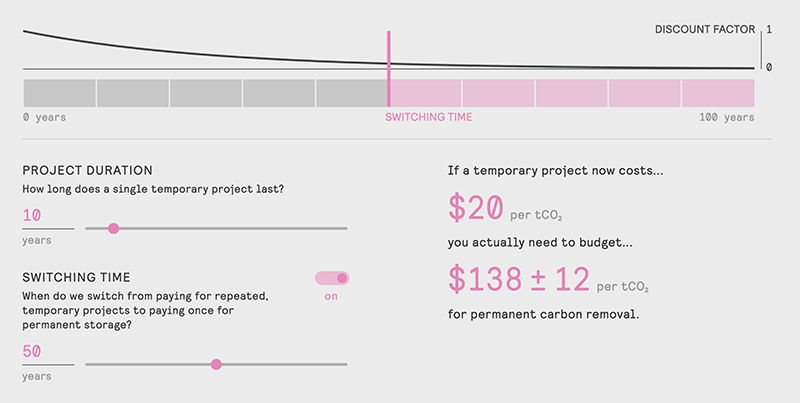

Permanence

CDR produces climate benefits by literally removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and sequestering it somewhere else. Reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations lowers the pace of global warming, but only so long as the carbon dioxide stays out of the atmosphere. Getting the timeframe of carbon storage right is a critical issue because temporary removals produce only temporary benefits — yet that’s what many of the lowest-cost CDR options produce today.

Some carbon removal methods are at a higher risk of reversal than others. For example, the now-annual wildfires in the Pacific Northwest have burned away forests that are part of California’s forest carbon offset program. Although these forests were supposed to provide climate benefits for 100 years, a large fire in Oregon burned a significant area of an offset project, sending a significant share of forest carbon back into the atmosphere. California’s program includes an insurance mechanism to cover unexpected losses from such projects, but unfortunately that system doesn’t take into account geographical variation in risks nor the fact that wildfire risks are rising along with the planet’s temperatures — and as far as we know, no public or private protocols are yet doing any better. (It’s worth noting that most forest carbon offsets, including California’s, do not primarily produce carbon removal. Instead, most “improved forest management” credits are avoiding emissions as landowners promise not to harvest forests in exchange for valuable carbon credits.)

Other carbon removal strategies result in longer-term storage. For example, direct air capture uses chemical reactions to pull carbon dioxide out of the air. Carbon dioxide can then be mineralized, transforming it into what is essentially a rock. It can also be injected into saline aquifers and other geologic formations. The risk of seepage where the CO2 escapes back into the air is higher in these formations compared to mineralization, and varies across geographies depending on the regulatory requirements. Industries have been injecting carbon dioxide underground for decades, with an estimated 78% to 98% of injected CO2 remaining underground for the next 10,000 years. In the United States, state and federal regulations — such as California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s regulation of Class VI injection wells — provide a blueprint for monitoring and strengthening of public oversight over underground carbon storage.

Differences in the permanence or duration of carbon removal make it hard to evaluate the cost of competing CDR strategies. To help those designing or procuring carbon removal strategies, Climateworks and CarbonPlan partnered to produce a permanence calculator.

Because competing carbon removal projects feature different time horizons over which carbon is removed and stored outside the atmosphere, it is difficult to compare their relative costs. The calculator shows how different combinations of temporary and permanent carbon storage projects produce permanent climate benefits, helping users such as governments and corporate decisionmakers explore the levelized cost of alternative CDR strategies. A key insight from this analysis is that the full economic cost of a permanent carbon removal strategy based on temporary carbon removal efforts can be significantly higher than the upfront cost of a single, short-duration project — in other words, a big part of the current cost difference between temporary and permanent carbon removal projects reflects the greater climate benefits delivered by permanent efforts.

Accurately measuring CO2 removal

It might sound deceptively simple, but accurately measuring carbon dioxide removal is another important and often overlooked challenge. For some approaches, particularly those involving biological systems, complex science and new technologies are needed to get a clear and cost-effective handle on the carbon cycle implications of changes in land management.

The good news is that technology is progressing in many of the most challenging areas of measurement. The field of forest ecology, for example, has benefited from recent innovations in remote sensing from satellites and Lidar, enabling reliable carbon accounting at the landscape level. However, the ability to use low-cost remote sensing to generate broad insights is based, in no small part, on the fact that the U.S. government has been collecting public forest data for almost a hundred years; related projects in other areas of the world will continue to help ground-truth remote sensing techniques around the planet.

For carbon removal approaches that vary widely by location and land management practice, such as soil carbon, reliable quantification methods remain to be developed. New investments in public data collection could help calibrate and leverage remote sensing in some of these areas. While potentially expensive to scale, ongoing ground-truthing is required to provide confidence in climate outcomes.

For direct air capture and carbon mineralization, reliable measurements of volumetric carbon dioxide flow are more straightforward. For example, as part of the CarbFix project in Iceland, CO2 removed by direct air capture machines is then dissolved in water and passed through underground basalt aquifers to form carbonate minerals. The volume of CO2 removed in the direct air capture stage is easy to measure because it is 99% pure once it’s separated by heat from the chemical filters. After injecting this reliably measured flow underground, calcium isotopes are used to accurately quantify the amount of carbonate precipitated, and derive the amount of CO2 stored. Current tests suggest an overall carbon removal efficiency of 72 ± 5% via this method.

The need to differentiate carbon dioxide removal from traditional carbon offsets

The carbon offset concept was created decades ago as a way to lower the costs of mandatory carbon pricing schemes. At the time, it was thought that a global tax or carbon trading system was the most promising strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Offsets would help keep mitigation costs in check by allowing low-cost emission reductions from somewhere else to relieve expensive reductions required at home. For example, consider a refinery that, rather than spend billions on retrofits, pays a timber company not to cut down its forests for a prescribed period of time. The refinery keeps pumping carbon into the air, and the timber company makes a claimed change in its harvest rotations somewhere else.

As with many well-intentioned policies, the devil is in the details. Offsets have faced a variety of challenges, including consumer distrust in measurement, reporting, and verification; carbon leakage; and depending on the regulatory framework, perverse incentives to increase pollution in order to claim more credits. Meanwhile, concerns about the environmental justice implications of shifting where emissions are reduced — along with the co-benefits they generate locally — have led to growing community resistance to carbon offsetting policies. Our experience in climate action has taught us that developing broad social trust and buy-in are essential to successful mitigation strategies; more than one viable approach — such as carbon capture and storage as well as nuclear power — has been shelved due to a lack of public trust. As experience with the problems of carbon offsetting grows, equating traditional offsets with carbon removal risks creating guilt by association.

Carbon removal is at a critical juncture, both in the sense that many promising approaches are being tested in the field and that many public and private actors see the need to scale removal to address those emissions we can’t avoid in the decades ahead. The risk that carbon removal will be equated with traditional offsets is particularly concerning because the private market for carbon removal credits is almost entirely co-mingled with the incumbent carbon offsetting industry. This is a problem because traditional offsets credit activities avoid or reduce CO2 emissions, which competes with climate mitigation, whereas carbon removal addresses a different problem — cleaning up pollution from sources that remain or can’t be reduced after serious mitigation occurs. The economics of this co-mingling also work at cross purposes, because currently high-cost, high-quality carbon removal options can’t compete with cheaper traditional carbon offsets in the same market.

Carbon removal needs to take lessons from the challenging experience with carbon offsets to develop a robust regulatory framework that is realistic about the political self-interest of its participants. Supporters need to commit to serious and sustained vigilance to fight back against rent-seeking behaviors from companies and industries that want to take advantage of the positive perception of and support for carbon removal, whether those efforts are focused on “nature-based” solutions or cutting-edge industrial technologies that appeal to different customers and political constituencies.

Establishing a better framework is critical because the time horizon to achieve net-zero emissions is rapidly shrinking. Large-scale carbon removal could be needed as a climate backstop to neutralize remaining emissions from hard-to-decarbonize sectors such as agriculture and long-haul aviation. If the pace and extent of technological progress in these difficult sectors doesn’t accelerate, then a greater reliance on carbon removal might also be needed as a bridge to deeper climate change mitigation, or as a means to withdraw excess historical emissions from the atmosphere. Defining the conditions under which carbon removal is acceptable at scale is a complex and ethically challenging task that must be done transparently in order to avoid the “lock-in” of incumbent industries as well as the significant environmental and social consequences of large-scale CDR.

Conclusion

The world’s inability to agree upon and enact a coordinated and ambitious climate change mitigation strategy has now put us in a place where large-scale carbon removal will likely be needed as a complement to deep and sustained cuts in climate emissions — not as a replacement. The world must now invest heavily to scale up carbon removal solutions. A comprehensive investment strategy must be guided by a clear sense of the challenges that have come before as well as the complexity that lies ahead. We hope this short post provides a helpful description of three areas where additional work is needed from all stakeholders to set global CO2 emissions on a path to net zero by mid-century.