Separating carbon dioxide removals from reductions

On Earth Day, the European Union announced the most significant legal commitment to climate neutrality — the agreement of the European Climate Law. While the overall agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 55% by 2030 and reach climate neutrality by 2050 could be more ambitious, the details underpinning the deal were truly innovative. Beyond the emission reductions target is a set of foundations with leading-edge design critical for the future of climate policy. Specifically, the EU’s commitment to achieving negative emissions post-2050 and the delineation of greenhouse gas removal versus reduction.

As world governments grapple with the need for carbon dioxide removal — a set of climate tools deemed necessary by the U.S. Special Climate Envoy John Kerry — the EU approach to policy design offers important lessons for other governments looking to responsibly research and deploy carbon dioxide removal.

Recognizing the different roles played by CO2 reduction and removal

The revised EU target of 55% net reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 includes a capped contribution of 225 million tons from removal. This means the actual GHG emissions reduction target from the EU is 52.8%. With the cap on removals, the EU now effectively has separate targets for emission reductions and carbon removals in all but name.

While current removals are defined only from sinks of land-use, land use-change, and forestry (LULUCF), the Climate Law recognizes the need to develop natural and technological sinks. It also calls for the development of a regulatory framework to certify carbon removals based on robust monitoring and verification and tasked the newly-established European Scientific Advisory Board to identify promising research and innovation contributing to increasing removals.

After 2050, the EU has also agreed to ‘aim to achieve negative emissions,’ acknowledging for the first time that simply reaching net-zero is unlikely to be sufficient to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. It would mean that by 2051, the everyday activities of Europeans will need to remove more CO2 from the atmosphere than they emit. Multiple IPCC reports have made the point clear already, with John Kerry and the Indian government recently echoing this call, but legal recognition of this truth had been lacking. The path has now been set for a healthy framework for negative emissions.

Foundation for the responsible deployment of carbon dioxide removal

This innovative policy framework came about as a multiple-year effort by Bellona Europa and other NGOs, along with a group of policy experts and researchers concerned by the initial proposal of the ‘net’ target without distinguishing reduction and removal. The implication of having removals count toward an overall target means countries may be over-reliant on carbon removal and fall into similar trappings as poorly designed offsets, which ultimately delays meaningful climate action.

This de facto separation of reductions and removals addresses the above challenge head-on. It is now set in stone that the overwhelming majority of the EU’s mitigation efforts will need to be done by reducing emissions, with carbon removal helping to go the extra mile. It is a significant milestone for climate policy design which allows the much-needed deployment of negative emissions to go ahead without jeopardising efforts to reduce emissions in the first place. The overall potential for carbon removal will be limited by planetary and socio-economic boundaries, which means we need to ensure we use them as effectively as possible.

The separation also provides additional benefits going forward. Firstly, the targets for both emission reductions and carbon removals are now clear and unambiguous, a necessity when setting long-term objectives. Secondly, this will enable both to develop in parallel while providing the ‘safe space’ to address the difficulties of deploying carbon removal in practice, such as permanence, additionality, and market design.

Opportunities and challenges going forward

This is by no means the end of the conversation but marks a healthy start to one that is bound to be difficult and complicated. Now that there is a ground rule for reductions and removals to happen in parallel in the short-term, work will advance to set up the framework to deploy carbon removal so in the longer-term, these approaches can be robust enough to rely on.

As it stands, there is no commonly held definition of carbon dioxide removal in legislation. The Climate Law refers to removals as sinks, which is then associated with ‘agriculture, forestry, and land use sectors’ (otherwise known as LULUCF). The role of non-LULUCF removals – direct air capture, carbon mineralization, ocean carbon removals – is not yet explicit and requires further clarification. Concurrently, a rigorous framework with methodologies developed and backed by reputable institutions is needed to monitor, report, and verify carbon removals at the project level.

The lack of a consistent and widely accepted framework rules out the possibility of trading any type of carbon removal credit in a way that is robust and trustworthy. In the EU, the process of developing such a framework is ongoing and is expected to be published by 2023. Despite many calls for carbon removals to be included in the EU Emission Trade System, the European Commission has firmly rejected these suggestions, adding that it might be possible in the future once there is a trusted certification of removals in place.

Despite this lack of framework anywhere, there has been a rush to add carbon dioxide removal into voluntary markets on both sides of the Atlantic. The growing body of evidence highlights the inadequacy of offsetting fossil emissions with land-based removal credits, further reflecting the need for a portfolio-based approach to carbon dioxide removal research, demonstration, and deployment. However, only providing monetary incentives – as the U.S. government has done – leaves the newer CDR approaches that are more costly and durable at a disadvantage in the existing poorly structured marketplace. A complementary set of policies in incentivising and procurement along with government funding will help set up this nascent field for success.

Conclusion

Under the revised European Climate Law, the EU has set long-term climate targets as well as a cap on the contribution of removals, effectively separating them from emission reductions. This is a wise move that buys time for the EU to develop carbon dioxide removal approaches and establish a robust governance framework to reliably monitor and verify removal projects. Without this governance, the risk of delaying emission reductions would have been compounded by the lack of guarantees that any carbon we remove on paper is removed in reality. As we like to say, we can lie to ourselves, but we can’t lie to the atmosphere.

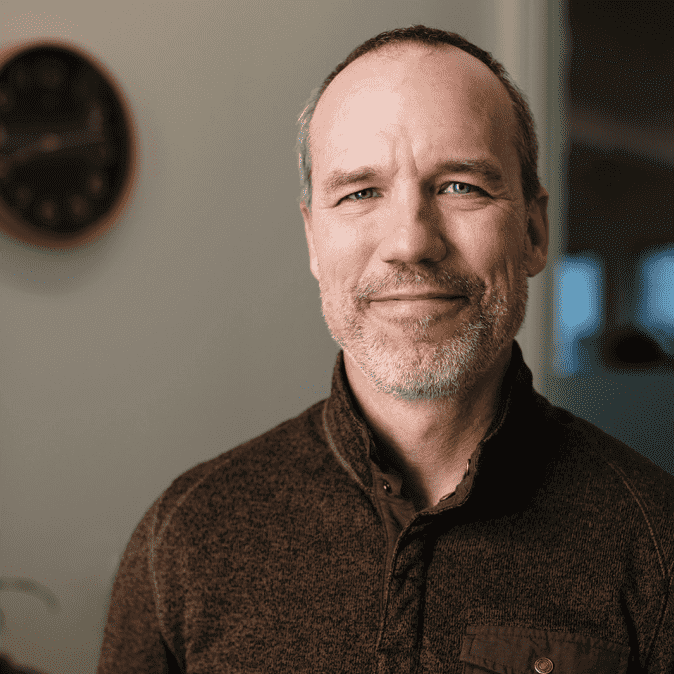

As our CEO of 8 years, Charlotte Pera, moves on to the vital role of shaping the future of the Bezos Earth Fund, ClimateWorks Foundation is fully committed to advancing our impact and extending our partnerships during this critical moment for climate progress.

We speak for the entire organization when we say that now is not a time to step back, but to keep moving forward with the speed and scale that the climate crisis demands.

As ClimateWorks embarks on a search for a next permanent CEO, our commitment to our partners during this transition is simple: we will stay keenly focused and deploy our collective capabilities towards fulfilling our mission.

This promise includes continuing to support bold climate solutions that have global scale. It also reflects our commitment to amplify the work of changemakers who deeply understand the needs of their local communities and are leading the way in building solutions. Equally important, we will continue to strengthen our efforts to fully embed diversity, equity, and inclusion into our practices, behaviors, and culture.

We are encouraged by the possibilities, motivated by the urgency, and committed to partnering with climate allies to meet this moment for transformation.

We look forward to continuing to learn from you and work with you in the effort.

In partnership,

Sue Tierney, Chair of the Board of Directors

Chris DeCardy, Acting CEO

Systems change and individual behavior change are not conflicting frameworks for how to mitigate climate change, they are two sides of the same coin.

The climate change mitigation community has long prioritized actions aimed at driving systems-level change to end the climate crisis, rather than focusing on changing individual behaviors. This has spurred some debate in recent years between these two models of how to achieve social change, but this is ultimately a false choice that distracts everyone from the real work of climate action and underestimates the power of individual choices that underpin social norms. Systems change and individual behavior change are not conflicting frameworks for how to mitigate climate change, they are two sides of the same coin, as organizations such as Climate Outreach and Rapid Transition Alliance argue.

In any society, individuals drive social norms that make up the collective culture. For instance, cultural revolutions don’t happen because of systems change; they happen when a group of people voice a compelling story that propagates across society and becomes a social norm.

In the context of climate change, those who support individual behavior change fear that if individuals in the Global North can’t adjust their consumption habits to protect the planet, then the 2-3 billion individuals entering the middle class in the Global South can’t be expected to do so either. Moreover, closer understanding of how personal habits contribute to climate change can orient us toward advocacy for aligned policies and practices.

Similarly, systems are made of people who make subjective choices every day, and those choices shape the systems as we know them. For climate change mitigation, systems change strategies entail influencing key organizational stakeholders to take actions that align with an emissions-free future and in turn influence the masses to take similar actions. Those who advocate for systems change fear that if we put too much focus on individual behavior change, we will stop holding corporations and governments accountable for their own impacts.

Both sides are valid, and therefore, it is not a choice between the two. We need to do better as individuals and we need to pressure politicians and companies to adopt policies and practices that speed up the transition to a sustainable economy.

Why this debate matters

We will only be able to confront the climate crisis if each and every one of us living in the Global North acknowledges that our way of life is contributing disproportionately to climate change and that we have the power to change course. In fact, research shows that simply telling people that their behavior is important for climate change mitigation encourages them to take action to reduce their emissions.

This raises an important distinction for thinking about the false choice between individual and systemic change: No matter how much (or little) responsibility individuals have for causing emissions, everybody has agency to create positive change. Taking action at the individual level has influence beyond the household, and that influence can be amplified in many ways:

- Effectively communicating about the changes we are making without moralizing,

- Constructively encouraging changes in the institutions we are part of, such as workplaces and schools; and

- Exploring the limitations of our personal actions as drivers for wider systems change.

It can feel inappropriate to call attention to individual behaviors in the face of a 2018 report showing that one-third of global emissions can be attributed to the 20 largest fossil fuel companies. However, history is full of examples of how principled individual actions were the basis for deeper social change, as evident by the rise of veganism in the U.K. and the rise of alternative meat companies. Moreover, there is a power in social contagion even when we aren’t trying to influence others through our actions. For instance, people are more likely to install solar panels on their homes if others in their neighborhood have done so.

Initiatives driving individual change

Following 2018 IPCC report calling for “wide-scale behavior changes” in addition to systems changes in order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, a number of initiatives have set out to drive individual behavior change that supports systems change:

- Rapid Transition Alliance showcases “evidence-based hope” about how positive change can happen surprisingly quickly, and the factors that make those deep and rapid changes more likely to happen and more enduring, including rapid behavior changes explored in the Lessons from Lockdown

- Scientists for Global Responsibility have developed a Science Oath for the Climate, where scientists are pledging to speak out on climate science, reduce their own emissions in order to demonstrate the possibilities for change, and hold their professional institutions accountable for both their emissions and affiliations with polluting industries.

- CIDSE´s Change for the Planet, Care for the People campaign takes a top-down and bottom-up approach to promoting sustainable living through grassroots activism with young Catholics and Catholic development agencies, and collaborative work with the Vatican and Catholic leadership at all levels.

These are just a few examples that highlight the ways in which individual power can add up to collective action and ways philanthropy can support this work.

What more philanthropy can do

Philanthropy can take several steps to be a key voice in shifting the discourse around the debate between individual and systems change:

- First, philanthropy can firmly acknowledge and debunk the false choice and be clear about the ways in which individual behavior change and systems change complement one another. Philanthropy can use the evidence base on how individuals catalyze systems change, such as “Individual behavior and system change: How are they connected?”

- Second, support intersectional campaigns that amplify the power of individual choices, such as the examples provided in the previous section.

- Third, walk the walk. Many organizations, including ClimateWorks, are starting to update their air travel policies (systems), which are upheld by staff (individuals), by engaging in an iterative process where individuals shape the system to correspond to the urgency of the climate crisis. Moreover, organizations have the institutional power to promote sustainable behavior across the climate community, for example by encouraging staff to favor remote working or limiting funding for face-to-face meetings.

Lastly, philanthropy can explore and support the power of individual behavior change by investing in programs and initiatives, or taking the actions that we’ve outlined in a previous blog.

(This piece was also published by the Hot or Cool Institute here.)

On April 30th, Charlotte Pera will end her eight and a half year tenure as President and CEO of ClimateWorks Foundation and begin on May 1st as the Vice President for Strategy and Programs at the Bezos Earth Fund.

Under Charlotte’s leadership, ClimateWorks developed global intelligence, collaboration, and grantmaking services to amplify the impact of climate philanthropy and made important contributions to climate mitigation through global programs focused on large-scale, global climate solutions.

The Board of Directors of the ClimateWorks Foundation has appointed Chris DeCardy as the Acting CEO and is preparing to launch a global search for a new CEO. Working closely with the strong Executive Team that Charlotte built, Chris and the board will ensure that ClimateWorks continues to advance climate progress at the speed and scale needed to end the climate crisis.

During Charlotte’s tenure, ClimateWorks grew its staff over three-fold, expanded its donor base to more than 40 donors, built its budget to more than $140 million in 2021, and moved approximately $640 million in grants to organizations advancing climate solutions around the world.

Sue Tierney, the Chairperson of ClimateWorks’ Board of Directors said: “Charlotte’s leadership has strengthened ClimateWorks and its extraordinarily capable team in every way. We don’t want her to go, but if she has to go, we can’t think of a better place for her to land. She will be an asset to the Earth Fund and to Andrew Steer. We wish them the best, because we’re counting on them to have an enormously positive impact, addressing the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the benefit of the people of the world. And the board has great confidence that ClimateWorks will move from strength to strength as it continues its crucial work to end the climate crisis by amplifying the power of philanthropy.”

Our work continues: 2021 is critical for making consequential and enduring climate progress. While organizational transition is never easy, ClimateWorks’ board and staff are confident that Charlotte is leaving the organization in a strong, healthy position. ClimateWorks remains fully committed to helping climate philanthropy do all that it can to help end the climate crisis in the critical year and decade ahead.

For questions regarding ClimateWorks Foundation, please contact Jennifer Rigney at jennifer.rigney@climateworks.org.

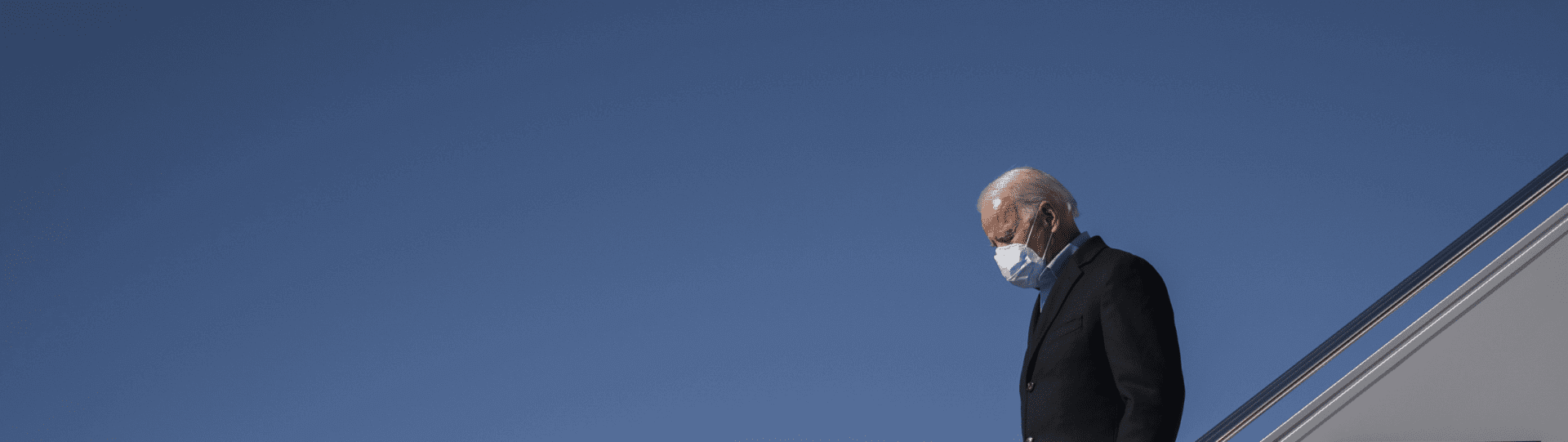

The Biden administration is expected to unveil its updated NDC soon, and the world is watching.

The United States’ complicated relationship with the Paris Agreement

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, over 190 countries have ratified the agreement and submitted Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to the U.N., detailing how they plan to reduce their emissions in line with a safe long-term climate. A key aspect of the Paris Agreement has been the nearly universal participation of countries around the world, with one especially notable exception: The U.S., the world’s second-largest greenhouse gas emitter, neglected to pursue national-level climate change mitigation actions under the Trump administration and went as far as withdrawing from the Agreement.

Under the leadership of the Biden administration, the United States officially rejoined the Paris Agreement in February. While reversing the previous administration’s withdrawal was a much-needed and welcome step, the United States will need to back it up with increased ambition and actions to restore its credibility and breathe new life into the NDC process, which was designed to encourage countries to ratchet up their mitigation ambitions every five years. The Biden administration is expected to unveil its updated NDC soon, and the world is watching.

An opportunity to realign with Paris

What, then, are we looking for in the new NDC? In a word: ambition. Based on a range of recently published analyses and scenarios, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions ranging from 50% to over 60% by 2030, relative to 2005, would put the U.S. on track to reach net-zero emissions before mid-century and realign itself with the goals of the Paris Agreement. More than 10 recent studies have shown that reductions of at least 50% by 2030 are both possible and desirable, though analysis from the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) estimates that the U.S. must reduce national emissions “by at least 57-63% below 2005 levels by 2030 and provide support to other countries” in order to ensure an equitable pathway to a safe climate. Another coalition of civil society groups, Fair Shares NDC, is calling for 70% emissions reductions domestically by 2030 compared to 2005, paired with large-scale climate finance to help other countries decarbonize. The large range of targets reflects different interpretations of the feasibility and equity of various emissions pathways, given the U.S.’ technological capacity and historical contributions to greenhouse gas emissions.

The top-level emissions reduction target is likely to garner the most headlines when the U.S. announces its NDC, but details on how this ambition will manifest across the real economy, from electricity to transport, and forestry to agriculture, is just as important as the headline number. We don’t know how much detail will be included in the NDC, but we do know how much action needs to be accelerated in order for the U.S. to transition to a Paris-compatible emissions pathway. Below are a few key examples drawn from the State of Climate Action report we published in November 2020 in partnership with the World Resources Institute, with contributions from the CAT:

In 2018, the U.S. produced roughly 17% of its electricity from renewable sources. While this percentage is growing, this needs to be a minimum of 50% and approaching much higher values (as much as 95%) by 2030. To achieve this will require accelerating the growth in renewable energy by a factor of approximately 5X per year this decade, which is ambitious and absolutely doable.

Similarly, the U.S. got as much as 29% of its electricity from coal-fired power generation in 2018. By 2030, this needs to be reduced to zero. While this is trending in the right direction (in 2020, initial data estimate that coal was down to approximately 19% of electricity generation), to achieve this target will require coal to decline as a share of electricity generation by around 2.5% per year this decade.

In 2017 in the U.S., electric vehicles made up only 1.1% of new vehicle sales. While this percentage is closer to 2% today, by 2030 this needs to be as much as 95%. To achieve this will require increasing electric vehicles’ share of new vehicle sales by approximately 7% per year this decade, in order to ensure electric vehicles make up at least 30% of the total vehicle stock by 2030.

The U.S. needs to simultaneously decrease deforestation while increasing forest coverage. This will require a roughly 4.5X reduction in the rate of deforestation during the 2020s, while more than doubling the rate of gross tree cover gain. Relatedly, the U.S. needs to see emissions from agricultural production decline by 20% by 2030. Achieving this would require emissions reductions of over 100 Mt CO2e by 2030, from a combination of increased agricultural productivity, decreased food waste, and dietary changes.

From ambition to action

The Biden administration recently announced the American Jobs Plan to invest unprecedented sums into clean energy, electric vehicles and public transportation, clean industry, and RD&D. The administration also put forward the Justice40 initiative, with the goal of targeting 40% of overall climate investment benefits toward disadvantaged communities. Both are inextricably tied to the just and equitable achievement of the NDC emission reductions targets.

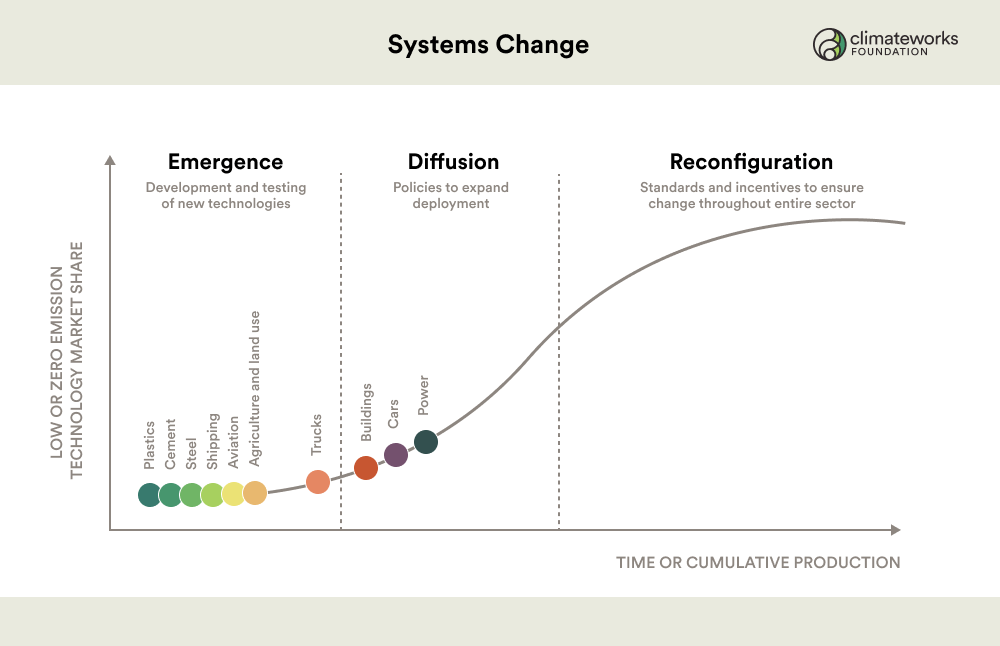

To be successful, these domestic actions must link with the upcoming NDC’s 2030 goals and move key sectors from the development and testing of new technologies, toward expanding deployment, eventually leading to broader systems change across society and the economy. Specific provisions in the American Jobs Plan aim to accelerate transitions already underway (e.g., electricity, cars, buildings), while also directing funding to many other key areas of the economy still in the emergence phase.

Source: State of climate action: Assessing progress toward 2030 and 2050

The U.S. rejoining the Paris Agreement was one step in the right direction. Now, an ambitious U.S. NDC, announced around the time of the upcoming Leaders Summit on Climate, must build on robust legislative and regulatory backing as well as a resolute implementation of the Justice40 commitment, to make these goals a reality and inspire further ambition and action from other countries and leaders.

Looking ahead

Beginning in 2022, the world will come together for the first Global Stocktake as part of the Paris Agreement. ClimateWorks is collaborating with a range of global institutions through the Independent Global Stocktake to prepare for this process and provide input. Demonstrable progress toward deep decarbonization of the U.S. economy will be necessary to convince the world that the U.S. is doing its part to contribute to the goals of the Paris Agreement. We will continue to call for greater detail and ambition in emissions targets and the rates of change needed to achieve them and hope the U.S. can play a leading role in tracking and reporting on progress toward key indicators in the years ahead.

Top-level greenhouse gas targets are important, and we will need to see an acceleration of progress throughout the entire economy. Ultimately, the Biden administration can set the overall direction of the U.S. commitment to fight climate change, but success will depend on the ability to translate that pledge into concrete action by the public and private sectors, civil society, and many other actors. Philanthropy has a vital role to play to accelerate change and ensure that these collective actions to achieve a healthy and thriving planet are successful. ClimateWorks will work with the philanthropic sector to keep pushing for ambition, emphasizing the need for justice and equity, and building accountability, over time.

***

Edit: Some statistics on the necessary sectoral emissions reductions have been updated to better reflect the State of Climate Action report.

On March 31, President Biden released the American Jobs Plan, a bold new initiative that could create jobs, advance climate solutions, and center justice in its implementation. Notably, the plan recommends $35 billion in clean energy research, $15 billion in climate demonstration projects, and $5 billion for climate-focused research. This package represents a major departure from previous presidential stimuli that heavily focused on shovel-ready programs, and is an important first step in correcting a decade-long stagnation of federal investments into research, development, and demonstration (RD&D). It is also significant in acknowledging a need to develop climate innovations such as direct air capture (DAC) and carbon storage — solutions that will bring new opportunities to U.S. industries, businesses, and workers in a global economy that is compatible with limiting global temperature rise to 2° C.

Government support is essential in advancing the RD&D for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) innovations needed now and in the decades to come in order to stay within safe temperature limits. The Energy Futures Initiative estimates the size of the need at $10.7 billion over 10 years, twice the amount announced in President Biden’s proposal for all climate research. While the American Jobs Plan calls for 10 demonstration projects for industrial carbon capture and 15 projects in clean hydrogen, the initiative is missing demonstrations that directly remove legacy carbon from the atmosphere (10 gigatons by 2050) or that utilize removed carbon for clean aviation fuels.

Support for long-term research and development has been a strong driver behind U.S. global leadership and competitiveness. For example, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) was critical in incubating and helping to scale important technologies such as artificial intelligence, an R&D initiative that started in the 1950s and has become a viable and essential technology we rely on today. Federal RD&D for carbon removal innovations is especially critical as it addresses two key barriers where 1) some approaches may be too risky or uncertain for the private industry to scale, or 2) where individual businesses could not expect to capture significant benefit for themselves within an acceptable investment horizon. Furthermore, aside from securing climate benefits and creating jobs, government support can ensure these new innovations are developed and scaled up in line with principles of equity and justice.

The need for carbon dioxide removal and adjacent innovations in zero-carbon fuels is one of the few climate solutions recognized and welcomed by bipartisan stakeholders. The 2020 Energy Act, the SCALE Act, and the USE IT Act all made clear calls for federal RD&D and procurement of direct air capture technologies, permanent storage, and other removal techniques. The increase from $50 per ton to $180 per ton of CO2 from DAC to permanent storage in the recent proposal to update the 45Q tax credit signals a thoughtful approach to carbon removal to complement, rather than replace, efforts in emission abatements.

Government support for CDR can also enable participatory processes that include the communities most impacted by climate change and who live in areas where projects may be built. A Rhodium Group report highlights that a robust direct air capture industry could create 300,000 jobs — more than the number of workers currently employed in natural gas — and present an opportunity for oil and gas workers to reapply their skills in climate-saving sectors. The operation and maintenance jobs at DAC plants could also be an important employment source for the surrounding communities. For example, the DAC plant being planned in California’s Salton Sea region could employ former agricultural workers who were at risk of losing their jobs due to soil degradation in the region.

Federal investments into carbon removal will spur the creation of an entire industry and open up a range of opportunities for U.S. manufacturing and labor for decades to come. Once the CO2 is removed, it can be safely transported to refineries and be converted to zero-carbon fuels. Paired with a scaled-up green hydrogen system, clean fuels can effectively replace emission-intensive fossil kerosene or reduce the land-use impacts of biofuels currently used in long-haul aviation. RD&D and the subsequent build-out of carbon removal technologies, its transport, storage, and/or utilization will also generate demand for many downstream industries such as concrete, steel, and construction.

President Biden’s proposal is the first step to “boost[ing] America’s innovative edge in markets where global leadership is up for grabs.” There is no question that investment from the federal government helped to make solar and wind the cheapest and cleanest energy sources for today’s grid, and the government has the opportunity to do the same now with carbon removal. Compared to the $20 billion allocated for general climate RD&D and a total of $500 million authorized for CDR from the federal government to date, clean energy will receive an additional $100 billion from the current iteration of the American Jobs Plan. We need carbon dioxide removal to effectively tackle the climate crisis. More catalytic and targeted investments from federal RD&D and procurement will help to create and bring down the cost of important solutions such as direct air capture and zero-carbon fuels.

The 2015 Paris Agreement represented a masterful feat of diplomacy: It was the first truly global undertaking, agreed to by nearly every nation, to tackle the climate crisis. But some of its most powerful provisions have only come into play recently, the cumulative effects of which may profoundly reshape the global economy over the coming decades.

Most obviously, the treaty’s “pledge and review” mechanism requires national governments to revisit their emissions reduction commitments every five years and revise them as climate science requires. The Biden administration is currently racing to develop a revised pledge in time for the summit it will host on Earth Day.

Less front and center, though equally important, was a commitment under Article 2.1(c) of the agreement to make global finance flows “consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.” This commitment should be understood to apply to more than just foreign direct investment flows into emerging economies. Rather, it applies to all financial flows, anywhere and everywhere in the world. In other words, and as recognized by President Biden’s January 27 executive order, Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement effectively requires alignment of the global economy with a pathway to net-zero global emissions by mid-century. This places an affirmative obligation on governments to regulate and supervise capital markets to achieve these objectives.

The U.S. government is now — finally — in the early stages of fulfilling this obligation, but the upcoming year will be critical in charting a feasible path to success.

Financial policy is climate policy

Today’s financial system inadequately accounts for the long-term physical and transition risks caused by climate change and the social, techno-economic, and political response to it. In 2017, the industry-led Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures recognized this as a market failure, unleashing a wave of attention to, and reporting on, climate risk. Since then, the conventional wisdom on managing climate risk has undergone a seismic shift from a purely market-led discussion to a clear expectation that regulators must step in. This global shift has left U.S. regulators scrambling to catch up to international peers, and they began signaling an interest in climate financial oversight even before the transition to the Biden administration. The attention of financial supervisors has also spurred the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and other market regulators to demonstrate that they, too, are prioritizing climate change.

“Financial policy as climate policy” was already relevant prior to the 2020 U.S. election, with governments around the world implementing regulatory strategies to integrate climate risk and promote green finance into their oversight of the financial system. Climate philanthropy has played a key role over the last several years, both by helping inform the terms of this agenda and driving its uptake.

But until 2020, U.S. financial system supervisors and capital markets regulators were largely asleep at the wheel when it came to climate risk.

Well in advance of the 2020 election, ClimateWorks initiated a strategy and grantmaking program to set the international agenda on climate financial regulation, understanding that the U.S. would, eventually, enter and in many ways become a leader in the space. This comes as no surprise, since U.S. capital markets are the largest in the world, representing 41% of global equity and 40% of global fixed income. What’s more, the U.S. dollar’s status as the global reserve currency ensures that the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department play an outsized role in shaping global financial flows.

It’s now well time for the U.S. not only to catch up to the international community on financial policy, but to take the lead.

A playbook for action

The extensive financial oversight powers and authorities of the U.S. executive branch allow the Biden administration to move quickly on climate financial regulation. We have been working with fellow funders to establish a coalition of long-time financial regulatory experts and advocates focused on promoting the reform of financial regulations to make them more equitable, just, and sustainable; climate should be one major pillar of the growing push for greater Wall Street accountability.

To that end, last year the ClimateWorks Finance Program partnered with Americans for Financial Reform, Public Citizen, and a team of contributing experts to develop a financial regulation playbook. “Climate Roadmap for U.S. Financial Regulation” details specifically how the Biden administration can protect investors, workers, and the American economy from the escalating risks caused by the climate crisis and align the complex regulatory framework governing the capital markets and financial system with the urgent transition to a low-carbon economy.

This playbook builds on prior calls for U.S. regulators to act, providing comprehensive, agency-by-agency guidance on how to do so. Although the report provides scores of technical recommendations on staffing, financial supervision, and market regulation, a few key themes emerge as priorities across the many agencies that conduct financial and market oversight. The core recommendations, paraphrased from the playbook, are:

- Firms should not be allowed to hide activities that are exposed to, or contribute to, climate risks. Regulators should require more accurate, comparable, standardized, and decision-useful climate-related disclosures for use by themselves, investors, and financial institutions.

- Investors must be able to act on climate reporting from companies. Regulators should protect and significantly expand investor and fiduciary rights to manage climate risk.

- Disclosure and investor empowerment are not enough. Regulators must use their authority to limit climate-related risks as they do other types of risk. Regulators should make substantive, prudential regulation a core pillar of the response to climate-related financial risks, and they should do so with the urgency befitting the climate crisis.

- Regulators must expand research on climate change’s effects on financial risk and the functioning of the market, even as they act to manage those risks. The need for further research is not an excuse for inaction, but it is also urgent, and will help regulators calibrate their actions over time. Coordination among financial regulators, FSOC, the White House, and international peers will be vital, as will outreach to environmental regulators and climate scientists throughout the Biden administration.

- Regulators must protect marginalized communities from being harmed by efforts to mitigate climate-related risk and prioritize efforts to advance equity and direct investments in sustainability and resilience to these communities.

The playbook calls for President Biden to issue an executive order on climate financial regulation, affirming that leadership begins at the top. The Biden White House can send a clear signal to both independent agencies and executive departments, ensuring forceful action by requesting or requiring, as appropriate to each agency’s mandate, that they prioritize climate in financial oversight.

Leadership must also come from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, to whom the Dodd-Frank Act bestows a vital interagency coordination role via the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). Our work on climate financial regulatory policy recommendations for the new administration has shown us that, perhaps even more so than in other domains, there are many parallel issues that arise in different regulatory bodies. Interagency coordination is vital to avoid a patchwork approach that could fail to respond adequately to systemic risk. Secretary Yellen presided over the first-ever FSOC meeting to address climate risk as the playbook report was published. This coordination process, together with senior personnel dedicated to climate-related issues at Treasury, the Federal Reserve, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and other relevant agencies will be essential to ensuring the U.S. has a comprehensive and coherent regulatory regime in place to tackle the climate crisis.

The path forward

Capital markets are just beginning to price in — and put money on — the now inevitable impacts of climate change and the accelerating low-carbon transition, but for many investors, businesses, and banks, the pathway to a net-zero emissions economy remains frustratingly unclear.

There are two ways forward. In the first, market actors continue to feel their way blindly through the transition, chasing special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) and other poorly regulated financial products to get exposure to the low-carbon economy, while at the same time inadvertently propping up high-carbon industries based on arcane risk management and portfolio optimization processes that rely on backward-looking data. In this scenario, the financial system as a whole will likely face considerable risks of green bubbles, public and policy backlash, and financial instability. The capital markets, only partially aligned with the low-carbon transition, will remain a hindrance, not a helper.

The other pathway sees financial supervisors and capital markets regulators take steps to ensure that companies clearly and candidly disclose how they will fare in a world of inevitable climate impacts and a shift to a low-carbon economy, that investors are empowered to act on this vital information, and that banks, insurers, and pensions are required to account for and reduce these risks in their stewardship of capital. Financial regulators have an affirmative duty to ensure our financial system is climate-smart, and now they have a playbook for how to do it.

We’ve just wrapped up the Confluence Climate Solutions Summit. The day was heavily devoted to “net-zero” – a much bandied term that seems to pop up everywhere these days, from country commitments to corporate targets to industry campaigns. Our break-out session tried to make sense of what this means for the impact investment community and philanthropy more broadly.

What exactly is net-zero?

In a sentence: Net-zero is a balancing of produced emissions with negative emissions. To be consistent with a 1.5⁰C warming scenario, we need to reach net-zero by mid-century, which will require us to decarbonize very rapidly.

First, we have to make significant reductions to our emissions through efficiency measures. ClimateWorks’ modeling shows that practically every sector of the economy provides emissions reductions possibilities. Second, there will remain some emissions that are hard or prohibitively expensive to reduce – residual emissions – which we have to balance in some way. Finally, this is not going to be enough to bring down the atmospheric concentration of CO2 consistent with a 1.5C scenario, so we need negative emissions beyond net-zero to remove legacy carbon from the atmosphere to reach our goal.

Let’s keep in mind that some sectors and geographies, notably the global south, might need more time to meet these targets, so from a climate equity standpoint, developed nations and the private sector have an obligation to strive for net-zero earlier.

Net-zero commitments

When a country or a company announces a net-zero commitment by a certain date, they’re saying that they will reduce their emissions to the extent possible and will remove any residual emissions by that date. Sounds clear enough – except that the devil is in the details and these commitments can be quite variable in their actual impact. To make sense of these commitments, let us unpack them:

- Which emissions are being considered? In carbon accounting parlance, is it Scopes 1 (direct emissions), 2 (indirect emissions on account of purchased electricity, steam, heating and cooling) and 3 (indirect emissions in the value chain)?

- How are these emissions going to be reduced? Scopes 1 and 2 are arguably within the company’s control, but how will Scope 3 reductions be achieved?

- How will residuals be offset? How robust are the carbon removal solutions envisaged? Are they truly maximizing reductions before using offsets? And what accountability is there in the offsets being used?

- What about historic emissions? Will there be any effort made to account for and remove the legacy carbon emissions already in the atmosphere?

- What are the milestones? Are there interim, more near-term targets to ensure that the longer-term commitments are on track?

Carbon removal and carbon offsets

Forests and nature-based solutions are age-old and regulate the planet’s CO2, while providing benefits to soil and water conservation. However, research from MIT indicates that offset programs through such solutions can significantly overstate carbon reductions. Technology-based carbon removal solutions would provide more permanent sequestration but are currently considerably more expensive. And there’s potential moral hazard: it may be cheaper for companies to buy offsets than do the really hard work of decarbonization in shipping or supply chains. Many feel that carbon sinks should be the last resort and limited to sectors that are really hard to decarbonize like aviation, heavy industry and methane from agriculture.

Getting to net-zero

Participants in our break-out didn’t need to be convinced of the need for net-zero, but most are grappling with how to implement this in practice. Many impact investees are small emerging companies that are just beginning to internalize climate and resilience considerations. Measurement and metrics are a huge challenge and pain point, and there is a real need for clear accounting protocols and tools that are adapted to the needs of small business. And measurement is just the first step!

It’s great that Confluence made net-zero the centerpiece of the Climate Solutions Summit – now we’re looking to the team to help us get there.

This post was originally published on Confluence Philanthropy’s blog here.

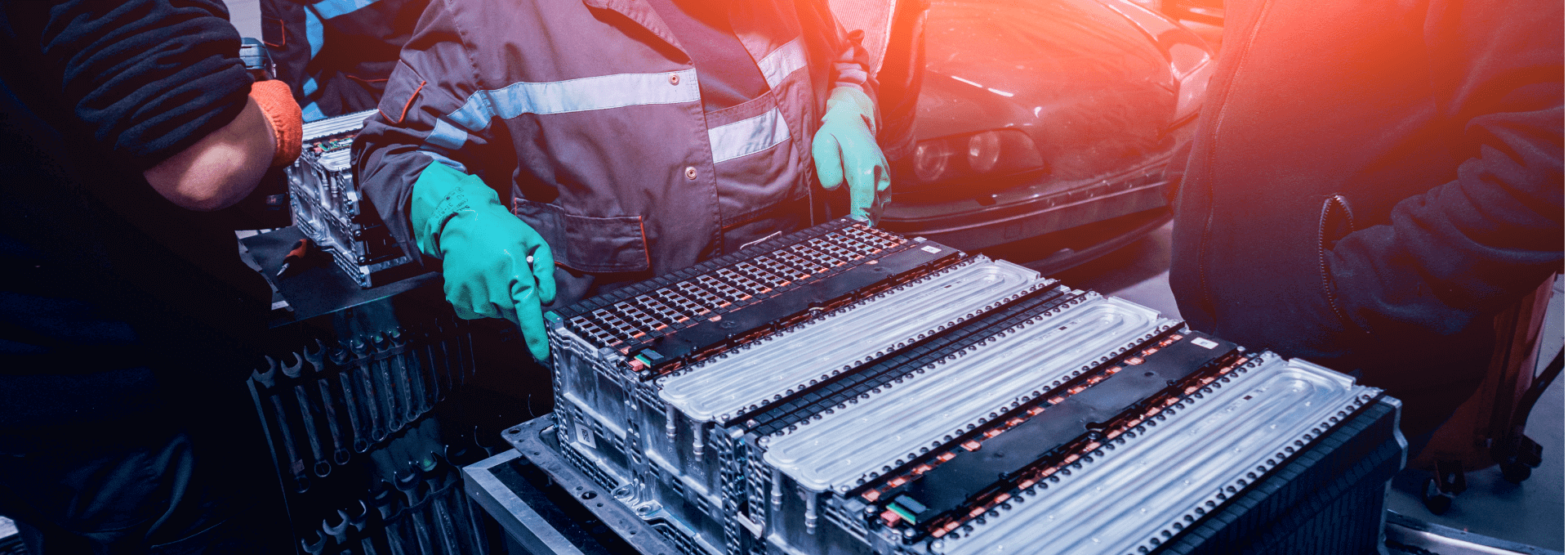

In the last five years, batteries have gone from being associated with ubiquitous AAs used to charge small electronics, to a prominent emblem of the clean energy transition. With 8.5 million electric vehicles (EVs) on the road today, batteries are on the path to single-handedly power transportation electrification through zero-emission vehicles, replacing polluting gasoline and diesel engines. As the world inches toward 100% electric road transportation across modes, as highlighted in the global Drive Electric Campaign, battery technology continues to rapidly improve. A recent report by Union of Concerned Scientists highlights that battery density has increased threefold from 24kWh in the 2010 Nissan Leaf to 75kWh in Tesla’s 2020 Model 3, while in the same time span, the average price of battery packs decreased from $1,200 per kWh to $137 per kWh.

Why batteries matter and how they need to be improved

The total emissions associated with manufacturing and operating electric vehicles are dramatically lower than those of a gasoline counterpart. The emissions savings range from 35% in countries with coal-heavy power generation, to 55% in the U.S. and countries with similar a grid mix. In Europe, an average electric vehicle is already three times better in terms of emissions than an average diesel or gasoline car.

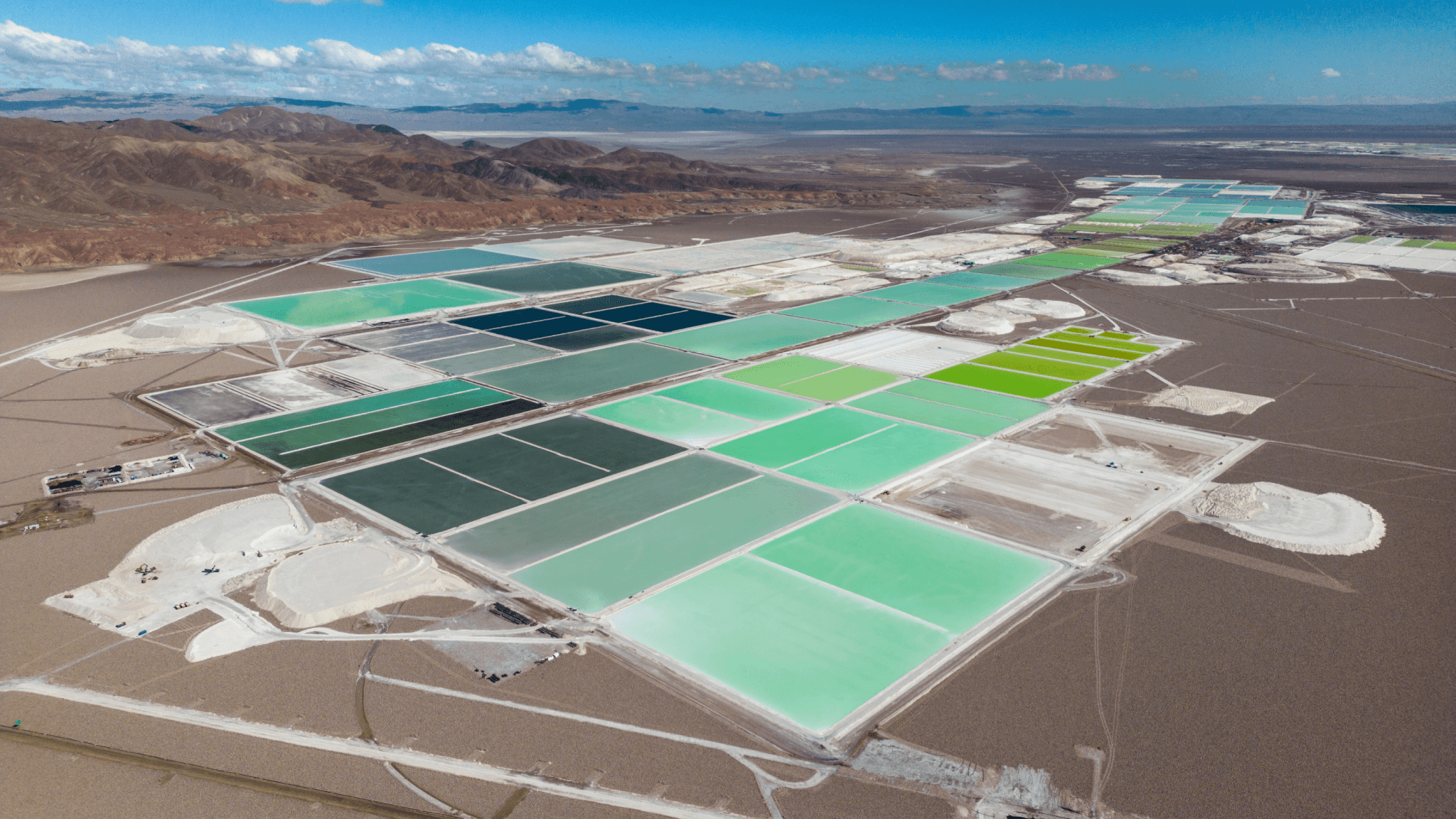

Battery manufacturing is the second-largest emissions hotspot in an electric vehicle’s lifetime emissions, but the impact will be reduced almost threefold in only a few years, due to better processes and scaled-up production. Where produced with clean high-renewables electricity, batteries are already low-carbon today. Beyond incentivizing low-carbon energy, ensuring battery materials such as cobalt, nickel, and lithium are recycled at the end of their life is essential. This already happens in China, and lawmakers in both California and Europe are putting in place ambitious circularity requirements. Finally, ethical sourcing of raw materials is the last key piece to the puzzle, ensuring that any metal that finds its way to an electric car (or any other vehicle) has been sourced responsibly, in line with the U.N.’s due diligence guidelines.

Policy and industry actions on EV batteries

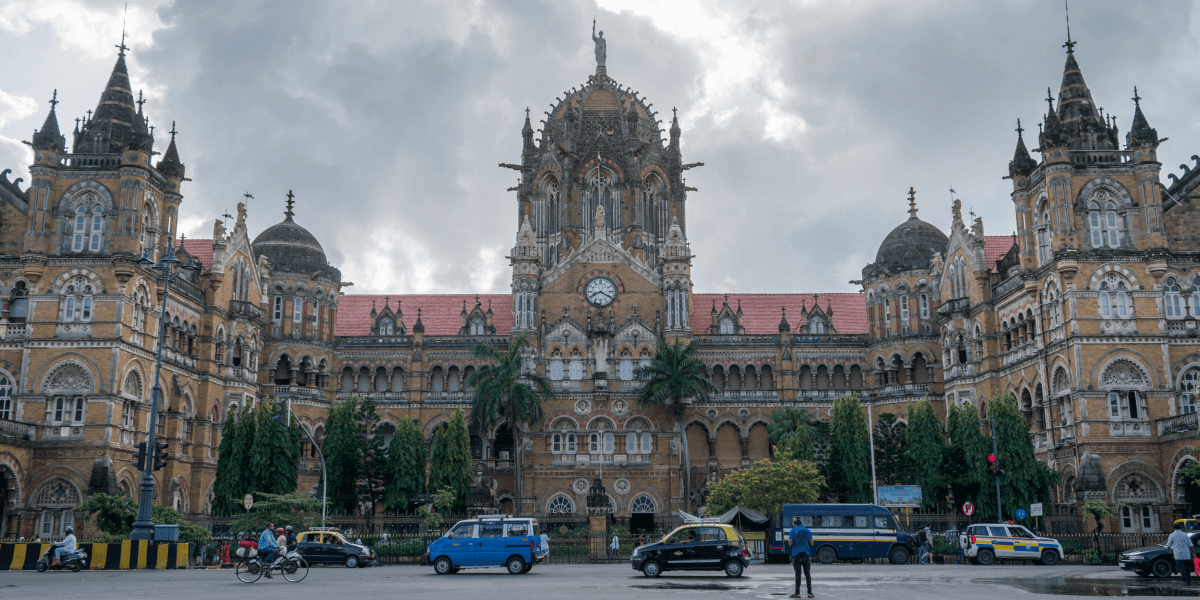

As electric vehicle uptake is ramping up, key markets are starting to take action to lock in sustainability practices across EV battery supply chains and position themselves as the hubs for battery production. Last year, the European Commission introduced a first-of-its-kind draft law seeking to set a precedent for a sustainable EV battery supply chain by mandating ethical sourcing, minimum recycling thresholds, and emissions disclosure. China enacted detailed policy and guidelines for recycling EV batteries and promoting second life uses. And India launched a National Programme on Advanced Chemistry Cell Battery Storage, which outlines an opportunity and plan for India to indigenize the production of battery cells.

On the supply chain side, the industry is starting to pick up pace in advancing best mining practices that preserve human rights and the environment. Most recently, Ford followed BMW and Daimler as the third automaker to join the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), the strongest voluntary commitment to bring transparency and accountability to their supply chains. The Global Battery Alliance (GBA) has also been set up as an industry forum to drive a sustainable battery value chain. While it can do more to push for fair mining practices in large-scale mining, its Battery Passport project is a notable step in the right direction

Philanthropic opportunity for sustainable EV battery supply chains

Despite meaningful recent progress, there is more to be done to lock in sustainable EV battery supply chains, and philanthropy can help by supporting several areas of work.

- Policy and best practices: Philanthropy can help elevate policies introduced in the EU, China, and India, and support learnings exchange across battery-producing countries. Policy packages should include recycling, ethical sourcing, production capacity, emissions disclosure and regulation, and circular design standards.

- Industry and supply chain: Philanthropy can support advocacy for industry to join platforms such as IRMA to drive and normalize sustainable supply chains that preserve human and labor rights as well as environmentally sound practices. It can also boost the ambition of organizations such as the GBA, as well as support better enforcement of existing standards and initiatives (rather than looking to new standards in an already complex matrix of initiatives).

- Emissions research and communications: Philanthropy can support non-governmental actors and academia to continue measuring and communicating the constantly improving emissions track record of batteries. A lot of myths, notably by electrification opponents, are still out there, so positive and simple stories showcasing clean, circular battery value chains are helpful to educate the public and policymakers.

- Energy transition opportunities: Philanthropy can facilitate broader thinking about the opportunities related to shaping the trajectory of practices within clean energy supply chains that center people and environment. This includes rethinking standards to promote best-in-class batteries, waste designation for EV batteries enabling end-of-life practices, international environmental and labor standards for mining and material processing for batteries entering the market, design standards to optimize recyclability, and many others.

Transportation electrification is set to correct decades of harmful exhaust fumes from gasoline and diesel engines by eliminating tailpipe emissions, reducing air pollution, and curbing related impacts to the respiratory health of communities in transport-dense areas such as cities, shipping depots, ports, and others. With proactive action on EV battery supply chains, there is an opportunity to shape the benefits of the clean energy transition even further, by locking in sustainable practices that center people and preserve the environment from the moment a battery mineral is safely sourced from the ground to the moment it is efficiently recycled back into a new battery.

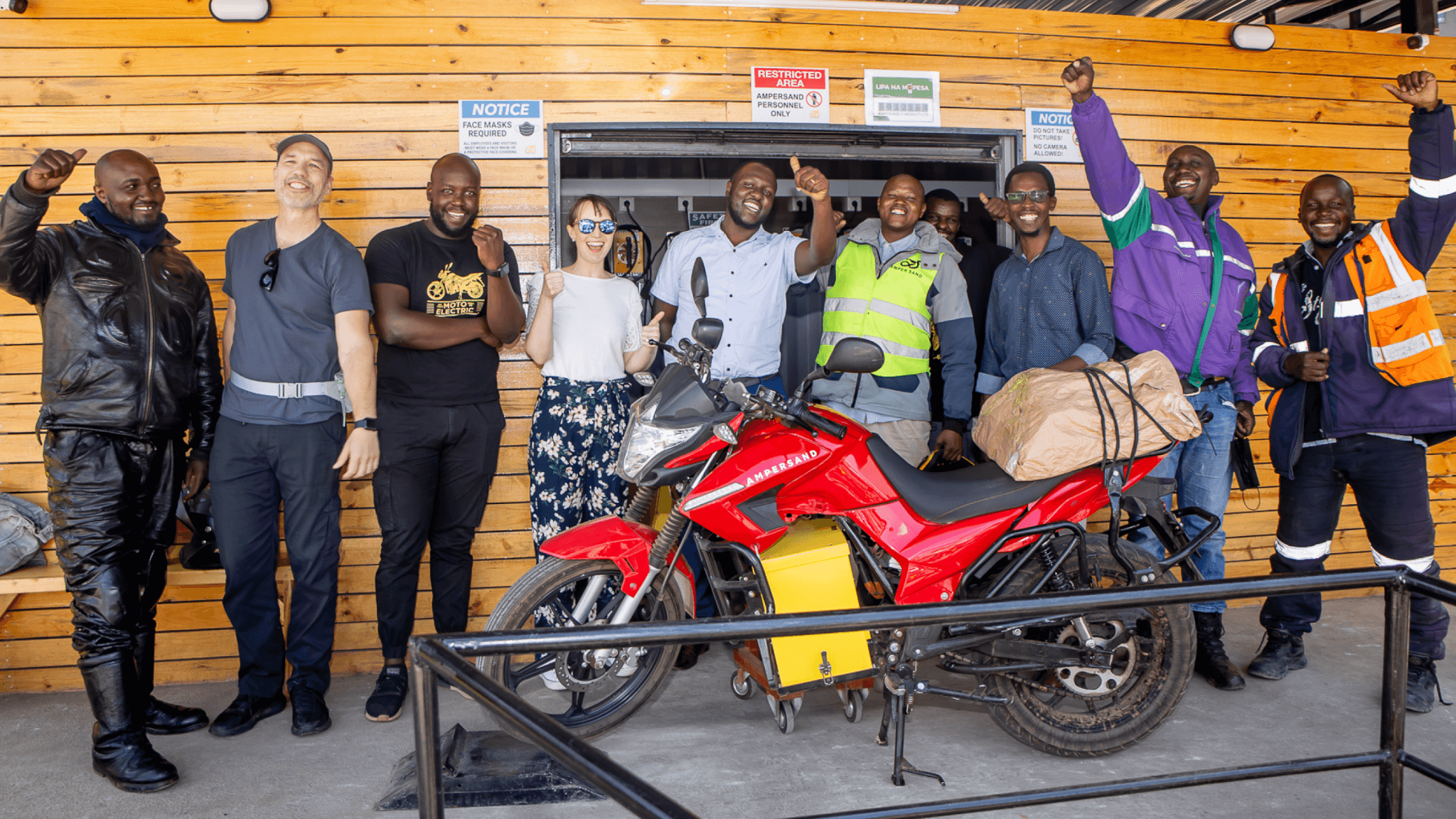

We are excited to announce the Drive Electric Campaign, a global effort to achieve 100% electric road transportation for the benefit of the climate, health and justice, and the economy.

Today’s combustion-based transportation system is inequitable, expensive, and contributes to enormous costs to the climate and our health.

The Drive Electric Campaign believes that a better future is possible. The rapid transition to electric vehicles (EVs) of all types — cars, vans, trucks, buses, and two- and three-wheelers, and e-bikes — can eliminate billions of tons of harmful emissions, save hundreds of thousands of lives per year, and prevent millions of cases of respiratory disease caused by pollution from combustion vehicles.

EVs also help the economy by creating opportunities for new investments and jobs in manufacturing and infrastructure — saving people money on fuel and maintenance, reducing oil demand that distorts geopolitics and the balance of trade, enabling greater renewable power generation, and avoiding trillions of dollars of climate-related damages linked to the burning of fossil fuels. Simply put, the electrification of road transportation vehicles is one of the most powerful, globally scalable solutions we have available now to achieve climate objectives while delivering a more equitable and just transportation system.

We know there is still a long way to go before we reach 100%. We are also increasingly confident we can win. Recent progress, supported by our partners, has created unprecedented momentum.

For example, over 100 national, state, and city governments representing nearly one-fifth of global transport demand have committed to 100% emission-free transport. They are banding together through initiatives like the International ZEV Alliance, Green and Healthy Streets, Global Drive 2 Zero, the Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Transition Council, the ZEV Community, and many others to pursue joint action on regulations and incentives to accelerate EV supply, demand, and infrastructure.

The private sector is stepping up as well. Vehicle manufacturers are investing hundreds of billions of dollars to bring new EV products to market and making commitments to shift to 100% zero-emission vehicle production by 2035 or earlier. Utilities are investing to enable charging infrastructure that can improve the integration of renewable power generation and provide benefits for all utility customers. Over 100 companies representing a fleet of over 4.8 million vehicles have committed to 100% electrification by 2030, including Baidu, DHL, Lyft, Leaseplan, IKEA, Ryder, Swiss Post, and the State Bank of India, among others.

Bigger, more powerful, and more diverse people-powered coalitions representing health, environment, business, labor, and frontline communities are banding together to demand stronger regulations and a better future. It’s working. In many countries, especially those with strong policy support, EV sales are trending rapidly upward even during the pandemic. With a sustained and concerted global effort, a tipping point is within reach as soon as 2025, when EVs could outcompete combustion vehicles on price, convenience, and performance.

Still, a complete transition at the speed and scale needed to save the climate is neither easy, nor inevitable. Those invested in the status quo are increasing their opposition and the risk is that, if we continue with business as usual or fall prey to the forces of inaction, the vast majority of vehicles will still run on polluting fossil fuels in 30 years, with dire consequences for the climate, public health, and the economy. As the world faces a decisive decade to put us on the path to a stable climate, now is the time to build on current momentum and pursue a bold campaign to overcome the remaining barriers and secure the path to a 100% zero-emission road transportation future.

Achieving this promising future requires systems change on a global scale. The Drive Electric Campaign collaborates with a diverse set of partners, including NGOs, foundations, and coalitions representing key stakeholders from government, business, and civil society, and focuses on three interconnected strategies:

- Supporting smart government policies that overcome barriers and grow the EV market, such as emission standards and EV sales targets for automakers, purchase incentives for consumers, public EV procurement, and many others.

- Encouraging business leadership and engagement such as by electrifying their fleets, supporting their employees and customers to adopt EVs, mobilizing finance and investors, engaging vehicle manufacturers to commit to a transition toward 100% zero-emission vehicle production, and increasing coordinated action and business support for key government policies.

- Engaging people power to drive transformative change by supporting diverse organizations and coalitions representing health, environment, labor, consumers, and business, and elevating the voices of communities affected by transportation pollution.

By working in partnership, the campaign takes a systems approach to secure commitments and actions that will put us on the path toward all new vehicle sales to be zero-emission by:

- 2030 for city and school buses and two- and three-wheelers;

- 2035 for passenger vehicles; and

- 2040 for freight trucks.

The end of polluting road transportation is within sight. But whether it happens in time to save the climate and fully realize the large potential social benefits depends on the actions we take together today. We invite you all to be a part of this movement to deliver a better future for our climate, health, and economy. To find out more, visit the Drive Electric Campaign website, which will be a hub for the campaign’s activities, highlighting the accomplishments of our partners and the growing momentum toward a 100% zero-emission road transportation future. This initial landing page launched today is just a start, and will expand over time. Sign up and join us for this journey.