How can a retail investor tell the difference between funds marketed as Green, Clean, Sustainable, Net-Zero, Low-Carbon, or Climate Impact? At worst they can’t, at best it’s not easy.

A surfeit of complicated naming conventions coupled with a lack of transparency in green-marketed investment funds create an “information asymmetry” between fund managers and individual investors. The result is a heightened potential for “greenwashing,” or marketing climate solutions that don’t hold up to scrutiny. In fact, all investors — whether an individual planning for her retirement or a large financial institution — can be easily misled without regulation that provides common standards to guide corporate disclosures and fund labeling.

This lack of transparency not only risks being deceptive, but it may also hold back the industry from supporting the capital flows that will be necessary in the low-carbon transition.

The dangers of greenwashing

Just last month, U.S. and German regulators began investigating the DWS Group after their former sustainability officer, Desiree Fixler, alleged that the German asset manager had greenwashed their total “ESG integrated” assets by applying an outmoded Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) risk management system. The DWS episode may be indicative of the wider market. A recent study by Influence Map shows that a majority of climate-themed funds aren’t aligned with the Paris Agreement. These challenges in the existing system may have a chilling effect on the market for climate investment funds, prompting former-BlackRock exec Tariq Fancy to warn that sustainable investing has become a “dangerous placebo” that harms the public interest.

These scandalous reveals are enough to make the market cynical as to whether climate-themed funds (or even woolier ESG funds) mean anything at all. That cynicism could be dangerous too. We need as many investors as possible to allocate capital toward the low-carbon transition to address the climate crisis. Individual and institutional investors are clamoring to invest in these vehicles, and that could super-charge change or amount to wasted heat.

Three types of climate funds

Instead of rejecting sustainable investing altogether, we need more simplicity and clarity regarding publicly-listed investment products being offered and how to assess the true climate attributes of a portfolio. While there are a growing number of climate-related offerings on the market, they typically span three broad approaches:

- Climate funds that screen out polluters: these funds generally have restrictions on buying fossil fuel linked assets — primarily coal, oil and gas. Screened portfolios were introduced to help investors align their portfolios with their values and avoid investments in controversial business activities. Recently, however, they are also seen as a tool to manage financial risk within investment companies and avoid the potential for stranded assets. While there’s still controversy about the real economic impacts of screened funds, there is also clearly demand for them, and consumers of financial services should be confident that a “fossil free” fund is truly fossil free.

- Climate funds designed to outperform financially: this newer category of climate funds seek to grow by investing in companies well positioned to benefit in a low-carbon economy. This can be done by targeting a particular set of companies or re-weighting the securities in a portfolio based on a companies’ preparedness for the low-carbon transition. These products are generally benchmarked to familiar indices and control differences in their “active” risk and investment return profile accordingly. This category may or may not exclude fossil fuel producers (sometimes they just reweight them based on a different calculus of a company’s value) and thus may have exposure to oil and gas, for example.

- Climate funds designed to have impact: In theory these funds are designed to help reduce global greenhouse gas emissions or create positive environmental change. In practice their impact is arguably the most difficult to demonstrate (particularly for a publicly listed investment strategy) as there is no consensus on how climate investment portfolios impact the real economy. These strategies can span direct investments in renewable infrastructure projects, to green bonds (bonds designed to fund environmental or climate projects), to funds that prioritize direct investor-company engagement and voting, for example.

It’s scandalous for an investor to think they are buying a “carbon-free” financial product when in reality the product is filled with fossil fuels. At the same time, in a functioning capital market that meets investors’ varied demands, each of these products can potentially appeal to different investors.[footnote tooltip=”Disclosure: One of the authors reviews the design of ESG funds as a judge for the UN Principles of Responsible Investing Award on innovation in ESG. https://www.unpri.org/showcasing-leadership/the-pri-awards/4189.article The other author previously worked on developing funds positioned to benefit from the low-carbon transition.”][/footnote] Given the differences in climate-themed approaches, though, what can be done to bring clarity to investors and stop greenwashing? This is precisely why we need prudent regulation.

How regulators can make climate investing simpler and more transparent

Introduced this year, the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation and accompanying sustainable finance proposals are a good first step to help evaluate and tier different climate investment approaches. In March of last year, the SEC solicited comments to improve the rules regulating how funds are named, and recently signaled that these rules should more strictly limit how ESG funds are marketed. But these don’t go far or fast enough. To preserve the integrity of a growing climate investment market, clear labeling and standardization needs to occur globally and consistently.

Financial regulators can stamp out greenwashing and improve the transparency of climate finance, starting with these three steps:

- Set standards for company data disclosure: clear standards for measuring and reporting emissions and sector-specific plans associated with the low-carbon transition are necessary so that funds and fund managers have clear and comparable data to assess. This is a prerequisite, upstream step to ensure climate funds can be appropriately assessed and labeled by investors.

- Provide clarity on the different climate fund approaches, consistent with consumer expectations: the categorization we presented above can serve as a starting point to help market participants better understand climate fund offerings and make choices accordingly. While there may be overlap between these categories (e.g., a climate fund designed to outperform may also have screens), a simple framework would bring more transparency and eliminate the more obvious forms of greenwashing. Rather than increasing the red tape for green funds, this should standardize and greatly simplify their marketing.

- Assess and disclose fund managers’ overall climate offerings: Many investors will want to consider the overall performance of the fund manager, and not just an individual fund. Fund manager disclosures could inform consumers of the composition of their climate offerings within total assets under management, and their performance on issues like climate voting. This would empower investors to make informed choices at the fund and fund manager level.

These priorities aren’t a panacea. For example, they leave open whether investment advisors are properly eliciting and responding to investors’ demands for sustainable products, which products have the most meaningful impact, or how to balance diversification and impact objectives. They do, however, lay a foundation on which further policy can be built.

To start, we hope that regulators will take the perspective of the credulous consumer when they inevitably ask themselves: is this prospective climate fund really doing what I am asking it to? In combination, these three steps can help reduce incidences of greenwashing, bring investors more transparency to inform their choices, and drive more capital toward investment funds designed to create change and support the low-carbon economy.

Let’s make it easy for investors to do the latter.

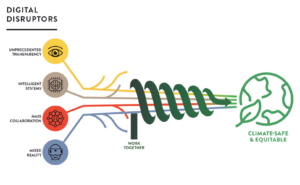

Our modern world is characterized by two central, human-driven forces: the digital age and climate change.

Digital innovations have influenced the lives of humans around the globe, pushing multiple levers of systems change. For example, the digital age has altered the global economy and labor markets, societal norms, flows of goods and information, and even our individual mindsets, influencing what we buy, who we listen to, and what we believe. Meanwhile, the impacts of climate change are increasingly affecting more of the global population, with continuing sea level rise, glacial retreat, increased forest fires, negative impacts on crop yields, changes to the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, and more. Further, dated governance structures and institutions are unable to adequately address the scale and complexity of the challenges climate change poses.

The opportunity to leverage digital age transformations for climate action

This digital age has the potential to unleash some of the large-scale societal transformations necessary to achieve the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and other global sustainability goals. However, this will only be possible if there is a concerted effort to overcome the risks associated with digital age transformations, which include the ecological footprint of digital technologies and threats to privacy and human dignity, and to encourage new forms of collaboration so that the digital disruptions underway help to advance a sustainable, climate-safe, and equitable world.

Overcoming key challenges to cross-sector cooperation

There is still a considerable disconnect between communities working with digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, climate data and governance, and philanthropy, who each have different perceptions of the risks and opportunities associated with leveraging digital age transformations for the climate. For example, AI is viewed more positively in the investment and finance sector, where AI projects have a relatively high success rate, as opposed to most other sectors, where 85% of AI projects actually fail. There is also a demonstrated lack of trust in AI and other digital technologies among the general public, including many within climate communities. Given predictions that digital technologies such as AI will continue to be used primarily to increase corporate profits and social control, this distrust is likely to continue. This tension may explain the lack of funding directed toward deploying digital technologies to accelerate climate action.

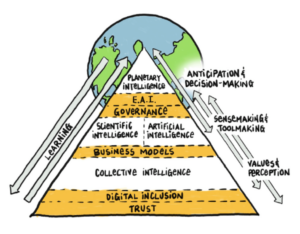

In order to leverage digital age transformations to tackle systemic crises such as climate change, we must develop planetary intelligence. This will include “collecting information at a planetary scale and using that information to understand the Earth as one interconnected social-biophysical system, assessing and predicting implications of changes for people and nature, providing transparency and accountability in environmental management, and shaping markets and policies to achieve sustainable outcomes.” Both the planetary intelligence model, as well as other recent reflections on sustainability in the digital age, demonstrate the importance of trust and inclusion as critical foundations to implementing systems change that will help humanity accelerate progress toward sustainability and equity goals.

The role of philanthropy

Building the necessary foundation of trust and inclusion will require engaging more fully across communities, sectors, and geographies. Philanthropy can play a key role in this space in many ways, including:

- Investing in relationship-building and collective intelligence with the explicit goal of identifying universal, inclusive, and digitally empowered solutions to climate governance challenges.

- Incentivizing partnerships that enrich the public commons with high-quality data that supports all stakeholders in harnessing the power of digital technologies to accelerate environmental sustainability.

- De-risking opportunities for other types of investment in digitally empowered climate change mitigation initiatives. For example, venture capital and impact investors can open up opportunities for innovative business models that leverage digital technologies.

The Re-imagining Climate Governance in the Digital Age project

Sustainability in the Digital Age (SDA), Future Earth, and ClimateWorks Foundation are partnering to explore this space through the Re-imagining Climate Governance in the Digital Age project. Through this project, we will develop a strategic framework and public report to help guide philanthropic investments and illustrate how philanthropy can support actors leveraging the digital sector to transform climate governance.

During the first phase of the project in the first half of 2021, we compiled a database of nearly 200 digitally enabled climate change mitigation initiatives in order to characterize the rapidly evolving landscape. These were categorized into four main levers for influencing climate governance: data mobilization to strengthen decision-making, digital optimization of existing strategies, incentivizing and automating behavioral change, and enhancing participation and empowerment. This database will be published in late 2021 alongside the strategic framework and report.

In the second half of 2021, we are engaging a diverse group of thought leaders. Several key themes have emerged during recent convenings:

- An emphasis on building relationships and trust as well as the need to explore new mechanisms for connecting bottom-up and top-down collaboration across all sectors,

- The need to identify funding and other gaps that are preventing society from leveraging digital technologies to accelerate climate action, and

- The importance of identifying key considerations for climate philanthropy to effectively engage with and invest at the nexus of digital innovation and climate action.

The ultimate goal of this work is to help grow and foster much-needed relationships and trust between disparate actors at the global nexus of digital innovation and environmental sustainability. Contact us to learn more about Re-imagining Climate Governance in the Digital Age, or reach out to Nilushi Kumarasinghe (nilushi.kumarasinghe@futureearth.org).

As Covid-19 brought the world to a grinding halt last spring, shared micromobility attracted rider attention as a more socially distanced means of travel. Though overall trends showed decreased ridership throughout the pandemic, bikeshare and scootershare operators saw new riders with its appeal of socially distanced mobility. A recent analysis by the North American Bikeshare and Scootershare Association (NABSA), “Shared micromobility: State of the industry report,” confirmed that shared micromobility played an important role in building urban resilience during the pandemic. This unique shared mode was pivotal in two ways: (1) it offered a distanced alternative to transit and (2) it integrated with public transportation to provide multimodal options for essential workers and lasting mobility impacts in equity zones, areas with high proportions of low-income residents who have been historically underserved by public transportation.

Personal mobility with built in social distance

In 2020, approximately 224 cities in North America had at least one bikeshare or scootershare system, with 33% of those cities having both. The rising accessibility of shared micromobility systems has allowed riders to make essential short-distance trips during the pandemic. Approximately half of shared micromobility systems surveyed by NABSA reported an increase in first-time riders. Bikes, in particular, saw an increase from 7 million trips in 2019 to almost 10 million trips during the pandemic. This upsurge came in response to public transit service cuts as cities grappled with adapting to Covid-19 safety protocols.

Even with service cuts and scale-backs to create Covid-19 safeguards, micromobility rebounded quicker than any other mode of transport, with 75% of suspended systems reopened and coming within 20% of the previous year’s ridership levels by the end of 2020. Micromobility’s versatility allowed for easier and faster adaptability in times of need. This showcase of resiliency affirms micromobility as a crucial component of transportation infrastructure as cities prepare for future public health crises and natural disasters. Moreover, the pandemic prompted cities to create temporary bike lanes and slow streets, allocate road space for outdoor dining, and recognize the need for permanent reallocation of public space that prioritizes the most efficient ways of travel.

Micromobility moved essential workers and equity

Micromobility operators and public officials came together early in the pandemic to offer discounted and free rides for essential workers to navigate closures. While public transit had to reduce services during the pandemic, micromobility rose to the occasion, with 55% of micromobility operators working with transit agencies to fill the gaps. The public-private partnership added resilience to the micromobility system, which proved to be essential for communities in transit deserts. Equity zones reported a 20% increase in trip-making. Shared micromobility also accounted for 7% of new trips that wouldn’t have been taken otherwise and a 20% increase in trips to essential services.

The increase in access to mobility in these equity zones has lasting impacts far beyond the pandemic. According to a study done by the Micromobility Coalition and DePaul University, when paired with walking and transit, 44% more jobs were accessible within 45 minutes or less with shared mobility. For instance, in Boston, individual residents gained access to 60% more employment opportunities when shared micromobility is an option along with transit and walking. With 50% of riders reporting that they already use shared micromobility to connect to transit, public-private collaboration can further improve equity within underserved communities by solidifying shared micromobility as a sustainable transport solution for the first and last mile of trips.

By advancing integration, the public and private sectors can work together to improve and increase accessibility to multimodal travel. Across North America, 83% of bikeshare and scootershare programs offer discounted pricing. Paired with payment integration, users can have greater ease of usability and affordability to travel across modes.

Keeping micromobility top of mind for philanthropy

Amidst a notable push to support and grow transit networks while maintaining momentum toward transport electrification to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals, micromobility often gets dropped off the list of priorities for philanthropy. However, as cities around the world continue to grow rapidly and experience more frequent and intense climate impacts, resilient and multimodal mobility will be crucial in the process of collective adaptation. As we’ve written previously, micromobility remains a key component of the energy transition and the philanthropic community can support in the following ways:

- Multimodality and connectivity: Building greater connectivity between existing transit and emerging shared mobility options, such as bikeshare and scootershare systems.

- Anti-racism in transportation policy: Working to dismantle structural racism in transportation policy, in addition to centering equity to benefit communities with limited access to safe and affordable public transportation.

- Reclaiming public space: Equitable restructuring of public space toward multimodal travel through curb pricing, zero-emission areas, dedicated lanes, slow streets, and others.

These philanthropic focus areas can also be incorporated into broader work in urban mobility that supports micromobility uptake, such as work on federal transportation funding, approaches that target regions for urban electrification, decarbonization of delivery vehicles, walkable city design, and many others. As philanthropy works to create more climate-responsive, resilient, equitable and just cities, micromobility should be an important part of those strategies.

Human activity can and must change now to avoid a climate catastrophe.

The latest report from the U.N.-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows the clear facts:

- Carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere are higher than at any time in at least 2 million years and concentrations of other greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide are at their highest levels over the past 800,000 years.

- We are already seeing damages from a 1.1° C rise in global average temperature since 1850-1900. We will likely hit 1.5° C in 2040, and continue warming thereafter, if we continue at the present pace of emissions increase. Limiting cumulative emissions and reaching net-zero carbon dioxide emissions, with sustained reductions in methane, can limit warming effects.

- Every fraction of a degree in temperature rise will lead to a larger number of extreme climate events that were once considered possible only once every 50-100 years, generating costly and devastating consequences for billions of people everywhere.

This scientific consensus embodied in the IPCC report is clear: We are on a disastrous climate pathway, and immediate steps are needed to support both near- and long-term solutions.

What does this mean for our philanthropic activities? There is absolutely no time to delay investing in every program or project that will all contribute immediately to avoiding a runaway climate disaster. Philanthropy should immediately consider:

- Urgently tackling short-term climate pollutants such as methane, particulate matter, nitrous oxides, and fluorinated gases as a near-term priority. Clearly, every fraction of a degree in warming matters, in order to avoid an increasing frequency of extreme weather events. It is the rate of warming, not just the total magnitude, that should worry us.

- Rapidly expanding renewable energy access and utilization, whether through centralized or distributed power grids, to ease the transition away from fossil fuel energy sources.

- Making climate-resilient infrastructure investments that help poor and climate-vulnerable countries to avoid untold losses among the hundreds of millions of people who bear the least responsibility for historical emissions and today still lack basic access to clean energy, air, and water. According to Oxfam, the richest 10% of the global population accounted for 52% of emissions between 1990 and 2015.

- Investing in the research and deployment of technologies that mimic nature and safely remove carbon dioxide from the air and also reverse surface ocean acidification. Global lands and oceans cannot keep absorbing higher cumulative levels of carbon dioxide emissions.

- Accelerating the societal transformations needed locally to adapt to new ways of manufacturing, transporting, and consuming goods. Top-down global solutions are not enough, and local action is needed to successfully align community lifestyles with a sustainable long-term climate.

- Supporting stronger financial incentives that promote climate transparency, disclosure, and risk mitigation among investors and policymakers. Money motivates change.

The Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the fragility of our interconnected world and the fact that nobody anywhere can escape a truly worldwide crisis. Just as inequitable approaches to vaccine distribution will lengthen the pandemic at a global scale, inequitable approaches to the climate crisis will bring serious negative consequences for all of us.

As climate change accelerates at an undeniable pace, so too must philanthropy accelerate its investments in solutions. While gradual progress is being made on that front, climate change mitigation funding still makes up less than 2% of total global philanthropic giving. Philanthropy can and must do more now.

More IPCC research and analysis to come

This analysis is based on the IPCC’s Working Group 1 report on the physical science of climate change. A report by Working Group 2 on climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, as well as a Working Group 3 report on climate change mitigation, are both expected in the first quarter of 2022. A summary report covering the findings of all three working groups is expected later in 2022. Stay tuned for more timely Global Intelligence analysis on how philanthropy should respond to the latest, most authoritative research on the climate crisis.

Learn more

Contact us to find out how we can help you build a climate change mitigation funding strategy that helps the world avoid a climate disaster.

***

Surabi Menon is a co-author of the 2007 IPCC report.

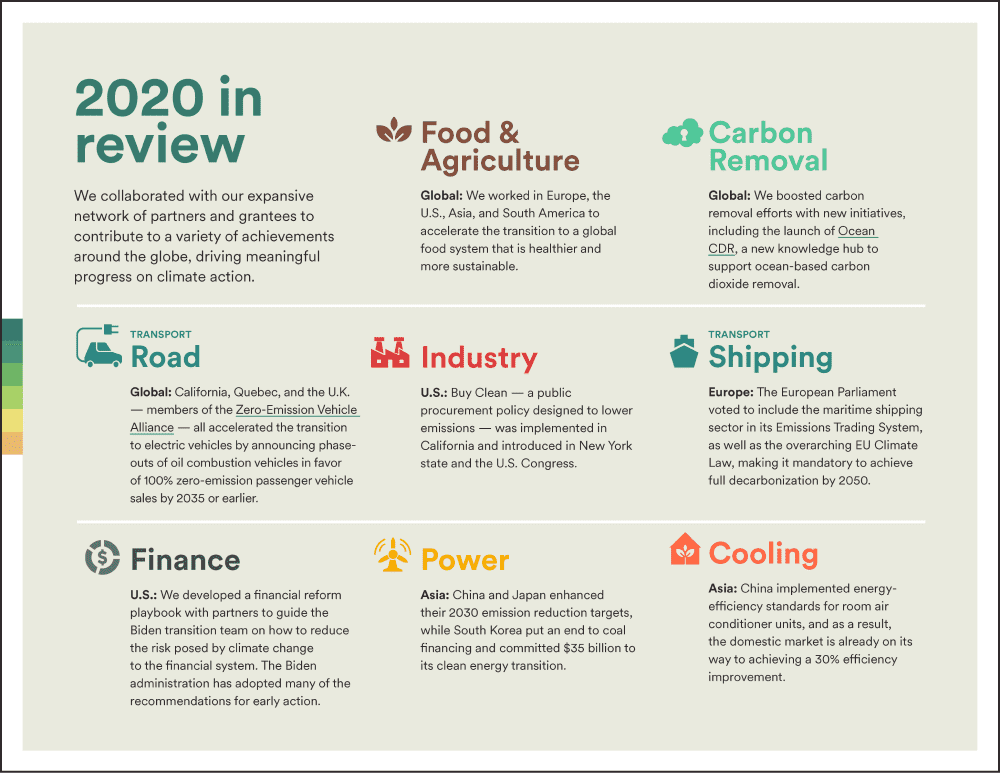

Today, ClimateWorks Foundation is releasing its 2020 annual report, which tells how ClimateWorks navigated a precarious year of crisis to continue advancing our mission to end the climate crisis by amplifying the power of philanthropy.

The report theme, Converging crises, converging solutions, reflects our view that 2020 was remarkable not just for the number and scale of challenges the world faced, but also the deep interconnections between them. From the escalating impacts of climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic to rising economic inequality and persistent social and racial injustices, 2020 underscored the need to broaden our perspectives and work together to overcome challenges and build a more inclusive, sustainable future for all.

In 2020, ClimateWorks collaborated with partners in over 40 countries worldwide to drive high-impact climate solutions on a global scale. We are grateful for the ongoing support and collaboration of our funders, grantees, and partners, which enabled us to increase our grantmaking dollars awarded by nearly 50%, reaching 386 grantees. We also helped climate philanthropy increase its collective impact by roughly doubling our intelligence publications and our convenings, reaching over 2,000 participants.

Our top highlights from the year include:

- Launched a new strategic plan and brand and began to re-examine ourselves and our work to better support climate, equity, and justice

- Drove sustainable Covid-19 recovery solutions to support the global transition toward a low-carbon economy

- Advanced equity and justice in our climate change mitigation efforts.

- Expanded our global network of grantees, funders, and partners to drive collective progress toward international climate goals.

- Further developed our collaborative platform to equip funders with the tools to ensure effective giving amid a rapidly changing landscape.

As much as this report is a review of work completed, it is also a call to action for the work ahead. We are encouraged by the progress we made in 2020, and we look forward to building on this momentum as we advance our vision of a planet that is a thriving home for all living beings for generations to come.

In response to the question of non-Party stakeholder input into the Global Stocktake, under consideration at the informal consultations on sources of input to the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement during the 2021 session of the SBSTA:

In response to the question of non-Party stakeholder input into the Global Stocktake, under consideration at the informal consultations on sources of input to the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement during the 2021 session of the SBSTA:

The independent Global Stocktake recognizes the essential role of the Global Stocktake (GST) as the Paris Agreement’s key mechanism to raise ambition across the themes of mitigation, adaptation, and finance flows and means of implementation and support, considering loss and damage and response measures, and in light of equity and the best available science.

Per Decision 19/CMA.1, the GST is to be conducted “in a comprehensive and facilitative manner.” To meet the mandate of being both comprehensive and facilitative, the inputs of non-Party stakeholders must be given due consideration throughout all phases of the GST process, including in the sources of input. Non-Party stakeholders hold unique and important knowledge, including indigenous and informal knowledge, and can play a crucial role in filling data gaps, sharing good practices and lessons learned, and synthesizing information that falls outside the scope of the mandated GST input.

A thoroughly participatory process, engaging stakeholders beyond Parties, will also help build up the political momentum within the GST that can trigger nationally enhanced ambition as well as increase climate action from non-state actors.

The GST can act as a driver of ambition only with equitable participation by all Parties and effective engagement with non-Party stakeholders and institutions outside the UNFCCC. Broad participation, including special attention to ensure equitable representation of observers from developing countries, will elevate the GST’s legitimacy and secure more international and domestic buy-in to the Paris goals. Observer participation will further encourage government accountability and advance the GST’s objective of enhancing international cooperation.

We look forward to continuing to engage to support a robust Global Stocktake.

———-

About the independent Global Stocktake

A set of partners launched the independent Global Stocktake (iGST) at COP24 to support maximum effectiveness of the Global Stocktake. The iGST supports alignment of the independent community — from modelers and analysts, to campaigners and advocates — so we can push together for a robust GST that empowers countries to take greater action on climate change.

The ultimate goal of the iGST is to see that 2025 national submissions and commitments reflect learning from the Stocktake and are made more ambitious by the process leading up to them. The iGST hopes to provide information that helps break down the implications of a global assessment for particular countries, regions, and sectors, and to work with interested Parties to uncover how lessons learned can be acted upon.

Most of the initiative’s thinking to date about how best to support an effective GST can be found in the “Designing a Robust Stocktake” Discussion Series:

- Synthesis Paper: A Vision for a Robust Global Stocktake

- Success Factors for the Global Stocktake under the Paris Agreement

- Guiding Questions for the Global Stocktake: What we know and what we don’t

- Design Options for the Global Stocktake: Lessons from other review processes

- Understanding Adaptation in the Global Stocktake

- Equity in the Global Stocktake and Independent Global Stocktake

- Understanding Finance in the Global Stocktake

- Mitigation Information and the Independent Global Stocktake

Additional analysis can be found on the websites of individual workstreams within the iGST consortium, such as these reports by the Finance Working Group:

- Seven ways the Global Stocktake can strengthen the post-2020 climate finance agenda

- Equity in financing climate action

- Loss and damage finance and its place in the Global Stocktake

- Consistency case studies: actions supporting Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement (Colombia and Switzerland case studies completed, first in an ongoing series)

The Paris Agreement outlines a five-year ambition cycle, anchored by the Global Stocktake and leading into enhanced national commitments every half-decade. We have only five of these 5-year cycles until we will be in the year 2050, when the world needs to be within striking distance of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

In recognition that there is no time to waste, the iGST is designed as a multi-faceted consortium with a nimble, fit for purpose structure. The consortium includes a set of complementary workstreams that act as platforms for dialogue and launching discrete pieces of work. These workstreams include regional civil society networks, work on the official GST process, and three thematic working groups loosely paralleling each of the main long-term goals of the Paris Agreement (on mitigation, adaptation, and finance), as well as another group focused on the cross-cutting theme of equity. Additional work occurs outside of the workstream structure, such as research currently underway on how the GST can be best leveraged to support national ambition.

The iGST welcomes the engagement of others providing advocacy and analysis to motivate countries to take on the commitments needed to combat global warming.

Nearly 18 months into the pandemic, many countries are making progress to keep Covid-19 at bay. However, the crisis is still ongoing in many parts of the world, with the virus surging in South America, parts of Asia, and a third wave beginning in Africa. The pandemic, like climate change, is a shared crisis. Progress on both fronts demands collective action, partnership, and the sharing of resources.

Next week’s meeting of the G-7 in Cornwall, U.K., is expected to focus on the challenges of Covid-19, economic recovery, and mitigating climate change. The meeting is a critical test of the world’s leading democracies to go beyond words to deliver concrete action that supports a healthy, sustainable, and just recovery worldwide. However, access to economic safety nets, vaccines, and health care has not been equitably shared so far. This imbalanced approach is not just amoral; it is also counterproductive and threatens hard-won progress everywhere. The G-7 gathering is a powerful opportunity to reverse this trend and signal that equity takes precedence by developing a roadmap to distribute Covid-19 vaccines to all and prioritizing emission reductions in ongoing economic stimulus efforts.

Leadership opportunities for the world’s largest polluters

The countries that are part of the G-7 have historically been the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. They bear considerable burden in setting the tone on how they are working to end the climate crisis through their own domestic actions and by providing the financial support for the hardest-hit nations recovering from Covid-19 and those that will be hit hard by the climate crisis.

According to Climate Watch, 48 parties representing 59 countries and 54% of global emissions have committed or communicated a net-zero emissions target by 2050. However, only 10% of these parties have passed legislation around their commitments. The rest include language around action to be taken in policy documents or in political pledges.

Indeed, very few of the countries represented at Cornwall have taken near-term domestic action that signals they are on a pathway to achieve those net-zero commitments by 2050. The U.K. and France are the exceptions.

Progress toward 2050 commitments cannot happen overnight. A closer look at how these attending countries (G7 plus Australia, India, South Africa, and South Korea) are performing relative to near-term 2030 targets shows woeful improvement. According to Climate Action Tracker assessments, U.S. climate action thus far is deemed critically insufficient, Germany and South Africa are highly insufficient, and Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and the U.K. are all insufficient. Notably, this tracker rates India’s action as compatible with limiting global warming to 2° C, based on equity, historical emissions, and other considerations. While these assessments are from 2020, and do not include commitments as a result of the Biden Summit in April this year, it is clear that until regulations and legislation are in play, we can only count these as unfulfilled commitments for now.

To ensure the integrity of net-zero emissions targets, the near-term domestic climate commitments by the G-7 members need scrutiny and transparency, which can help with their leadership on the global stage. Establishing a timeline to achieve even a few priorities will help reach a pathway to halving our greenhouse emissions by 2030 and achieving net-zero by 2050. The three key priorities are:

- Ensuring that climate action being implemented in the near term is inclusive, credible and driving toward net-zero,

- Ending financial support for fossil fuels, and redirecting support to a sustainable economic recovery from the pandemic, and

- Encouraging urgent, overdue contributions to the $100 billion in climate finance that rich countries promised to support climate action in developing countries.

Philanthropy, too, has an essential responsibility to work in partnership with civil society and non-state actors to stimulate significant national-level actions and support governments in delivering on their commitments. It is well-positioned to support climate solutions centered around equity and justice. With more new donors coming into the climate philanthropy space and established climate funders maintaining or increasing their commitments, there is a growing opportunity to collaborate and catalyze change to make as much progress on climate as possible during this decisive decade for action.

With the U.K. being the host for the G-7 and COP26 in November, all eyes are on how it will combine diplomacy with action. If G-7 governments can deliver on near-term Covid-19 and climate priorities, the world will be on a much healthier footing as pressure builds on all nations to commit to bolder, accelerated steps to limit mean global temperature rise to 1.5° C.

2020 was the year that showed why micromobility is vital for cities, and 2021 should be the year we re-imagine transportation systems with micromobility in mind.

When e-scooters were first dropped on the streets of San Francisco in 2018, it marked the beginning of an era of new personal mobility options in cities. Since then, e-scooters have been rapidly evolving to improve safety, enhance parking and operations in public spaces, adjust to city permitting guidelines, and even boost their overall sustainability. E-scooters also gave rise to the new umbrella classification called micromobility, including e-scooters, e-bikes, regular bikes, and anything else that reflects personal mobility moving at slower speeds.

While Covid-19 has severely reduced ridership on public transit across the globe, the pandemic has proved that resilient transportation systems require multiple options, and micromobility plays a key role in such systems. 2020 was the year that showed why micromobility is vital for cities, and 2021 should be the year we re-imagine transportation systems with micromobility in mind.

Two key steps to improving micromobility

The path forward for micromobility and urban mobility at large is twofold:

1. Concerted efforts to integrate micromobility with public transport as much as possible;

2. Centering equitable access to mobility by expanding travel options for BIPOC and low-income communities that do not live within walking distance of public transit stations.

In a forthcoming report, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) highlights global best practices for integrating micromobility into transit systems, recognizing that improving integration expands access for users, but also benefits operators and cities. While physical integration is common in many cities, like locating micromobility parking areas near transit stations, more advanced integration could yield greater benefits for users and cities. For example, trip-planning resources that integrate multiple modes of travel can build users’ confidence to make multimodal trips. Payment integration makes multimodal travel even more attractive, enabling users to pay once for a trip that requires using multiple modes of travel, or receive discounts on one or more modes. These types of integration require proactive city intervention and working closely with operators to ensure alignment with integration goals.

Leveraging the new guide, ITDP is working with the cities of Chennai and Jakarta to pilot projects to improve physical and informational integration. In Chennai, as part of a planned public bikeshare system expansion, the pilot focuses on siting new public bikeshare stations at major bus terminals to improve physical integration between these modes. E-bikes are also being added to the system — a first for public bikeshare in India — to serve longer trips. In Jakarta, improved navigational resources at key transit stations direct people to new bikeshare parking areas and provide information on nearby points of interest and cycle routes.

Similarly, partners at New Urban Mobility Alliance (NUMO) have been working with cities in Latin America to develop new options for cycling and transit as systems recover from the pandemic. For example, at the start of the lockdown in Bogotá, a hackathon helped to rapidly collate data and deploy new initiatives, including introducing new bus routes and e-bikes for healthcare workers. The city also committed to make permanent 80 km of emergency bike lanes and mobilized input from 7000 citizens to redesign a major street into a “green corridor.” The organization’s COVIDMobilityWorks.org platform documents over 100 cities globally that dedicated street space for cyclists and pedestrians during the pandemic. This has been accompanied with a surge in use of shared bicycle systems and bicycle sales globally. Despite these positive indicators, it is yet to be seen whether cities follow the example of Bogotá and make this infrastructure permanent as vaccines roll out and the risk of infection declines.

Simultaneously, the current re-imagining of transportation systems is the moment to prioritize equitable reach and improved service for people whom the system fails. While safe infrastructure is critical for micromobility uptake, our definition of “safety” must go beyond infrastructure to include safety from over-policing and racial profiling. Micromobility infrastructure needs to appropriately consider the disproportionate risks to personal safety that Black and Brown cyclists face and be built out in a way that centers and benefits them first and foremost. Re-imagining urban mobility, micromobility expansion, and electrification of transport with social and racial justice at the center, offer an opportunity to address and dismantle systemic racism that is embedded in many transportation policies today.

Philanthropy’s role

While transportation electrification is a key solution for reducing emissions, in cities, electrification needs to be combined with better connectivity and equity, in order to drive the most positive impact. In addition to shifting to climate-friendly modes of transport such as clean transit, biking, walking, and shared mobility, philanthropic work on transportation in cities should also focus on:

- Multimodality and connectivity: Greater connectivity between existing transit and emerging shared mobility options, such as private bikeshare and e-scooter share systems.

- Anti-racism in transportation policy: Working to dismantle structural racism in transportation policy in addition to centering equity to benefit communities with limited access to safe and affordable public transportation.

- Reclaiming public space: Equitable restructuring of public space toward multimodal travel through curb pricing, zero-emission areas, dedicated lanes, slow streets, and others.

Policy tools, mobility technologies, and public appetite are all in place to shape the future of sustainable mobility systems today — all we need is philanthropic support and greater political ambition.

Though we’re not yet halfway through 2021, it’s already shaping up to be a banner year for tackling climate change – politically, financially, and socially. Any consumer taking in the tidal wave of climate news will be able to cite numerous examples of action and yet science demands more action to keep warming below 1.5° C. Thankfully more is coming.

One of the most critical goals to achieve in 2021 is an enhanced Paris Agreement, which means negotiating issues like carbon markets, finance, and reporting, but perhaps more significantly, updating Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for climate mitigation and adaptation. NDCs are a fundamental component because they detail the targets, policies, and measures governments aim to implement over the next five years. Each country must submit an updated NDC to the UN by COP26 in November this year.

While most parties are still working on enhancing their plans, 81 countries (as of May 1) have already updated their NDCs or submitted entirely new ones. And to that we say ‘Bravo!’. Even more exciting (in our eyes) is an emerging trend that we’re seeing in these recently published NDCs, one that has huge mitigation potential. Currently, this mitigation potential is roughly 7% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, although this is expected to double by 2050 if left unchecked. Not only does this trend have the potential to avoid a sizable chuck of global emissions, it’s also critical for adapting to the warming climate and delivering multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) relating to health, nutrition, productivity, and education.

So, what is this trend? Well, it’s quite simply committing to the adoption of or transition to energy-efficient, climate-friendly cooling solutions. So far, 22 NDCs – representing 48 countries – have featured cooling commitments or reference to it, with at least seven countries signaling they will include action on climate-friendly cooling in their NDC when they go to print.

A new briefing paper from the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (K-CEP) summarizes the state of play and includes 10 case studies of published or planned NDC enhancements featuring climate-friendly cooling. This work is being done as part of K-CEP’s NDC Support Facility for Efficient, Climate-Friendly Cooling, which was set up to help developing countries that are committing to take action on cooling in support of the Paris Agreement. The brief goes on to give an overview of 45 additional countries (including the 27 members of the European Union) that have already included climate-friendly cooling in their enhanced NDCs in some form.

Government action on efficient, climate-friendly cooling

While most governments tend to focus on the supply side of the energy transition and shifting from fossil fuels to clean power, many of these 55 countries have recognized the need to also look through the other end of the telescope, managing energy demand as well as the use of refrigerants that have a high global warming potential (GWP). They have understood that energy supply is just a means to an end, not the end itself, and that it is the benefits we receive from energy, such as cooling, that matter. The more efficiently we can deliver these benefits in terms of energy supplied for benefits produced, the cheaper the cost of the energy transition will be and the quicker we can do it. The Economist Intelligence Unit recently quantified these cost and time reductions and estimated that efficient cooling (in appliances and buildings) can save $3.5 trillion by 2030 and take eight years off the transition to net zero.

Making our cooling more energy efficient can be achieved at the product level, like in air-conditioners (ACs) and refrigerators, or at the system level, such as buildings, cities, and grids. Enhanced NDC commitments on cooling reflect the different entry points for efficient cooling. For example, Nigeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Pakistan will be focusing on more stringent Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) for ACs and refrigerators, while Cambodia, Vietnam, Burkina Faso, and Jordan will be upgrading their public buildings and cities. Alternatively, Ethiopia and Chile are focusing on industrial cooling.

In parallel with NDC enhancements, 118 countries and the European Union have now also ratified the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, which aims to reduce the production and use of super-polluting hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), 86% of which are accounted for in cooling equipment (in GWP-weighted tons CO2-eq terms). Better alignment of these two regimes (i.e., the Paris Agreement and the Kigali Amendment) will help countries to reduce emissions from cooling faster and more cost-effectively.

Cooling our warming world

As we ‘build back better’ we also need to ‘build back cooler’, ensuring that cooling equipment and appliances, as well as buildings, are net zero, and that the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic also focuses on cooling our warming world. In doing so there are huge opportunities to address racial and social equity challenges by reducing the cost of cooling for low-income consumers, retrofitting buildings for comfort and health, and making public spaces ‘cool havens’ to provide respite from the heat waves that challenge our way of life more and more each year.

With the publication of the COP26 High Level Champions’ Climate Action Pathway to Net-zero Cooling, we know how to get to net-zero cooling – passive buildings, super-efficient equipment and appliances, and ultra-low (< 5) GWP refrigerants – but now we have to ensure the necessary actions are taken to get us there.

Of the 189 parties that have joined the Paris Agreement, the majority still need to submit enhanced NDCs by COP26 this November, and many need to ratify the Kigali Amendment.

Enhanced NDC commitments on cooling are an important step in the right direction on this sectoral pathway. The benefits are clear. Of the 189 parties that have joined the Paris Agreement, the majority still need to submit enhanced NDCs by COP26 this November, and many need to ratify the Kigali Amendment. Taking ambitious action on both fronts would provide a valuable opportunity to realize the full mitigation potential of energy-efficient, climate-friendly cooling.

The recent announcements from the U.S. and China – namely their Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis (including the phasedown of HFCs), both countries’ decision to ratify the Kigali Amendment, and the United States’ enhanced NDC and American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act – has puts some serious wind under the wings of the Kigali Amendment, its significance in geopolitical terms, and what it means for the cooling industry overall. That said, more emphasis is needed on cooling more broadly, such as appliance efficiency standards. A renewed spotlight on the efficiency of cooling appliances, building design, and the HFC phasedown as a complete suite of critical climate solutions simply can’t come soon enough. Temperatures are rising and the clock is ticking for people and planet.

Further info

For more information on the importance of efficient, climate-friendly cooling for all or K-CEP, please visit www.k-cep.org.

Governments interested in enhancing their NDCs with action on climate-friendly cooling please email k-cep@climateworks.org.