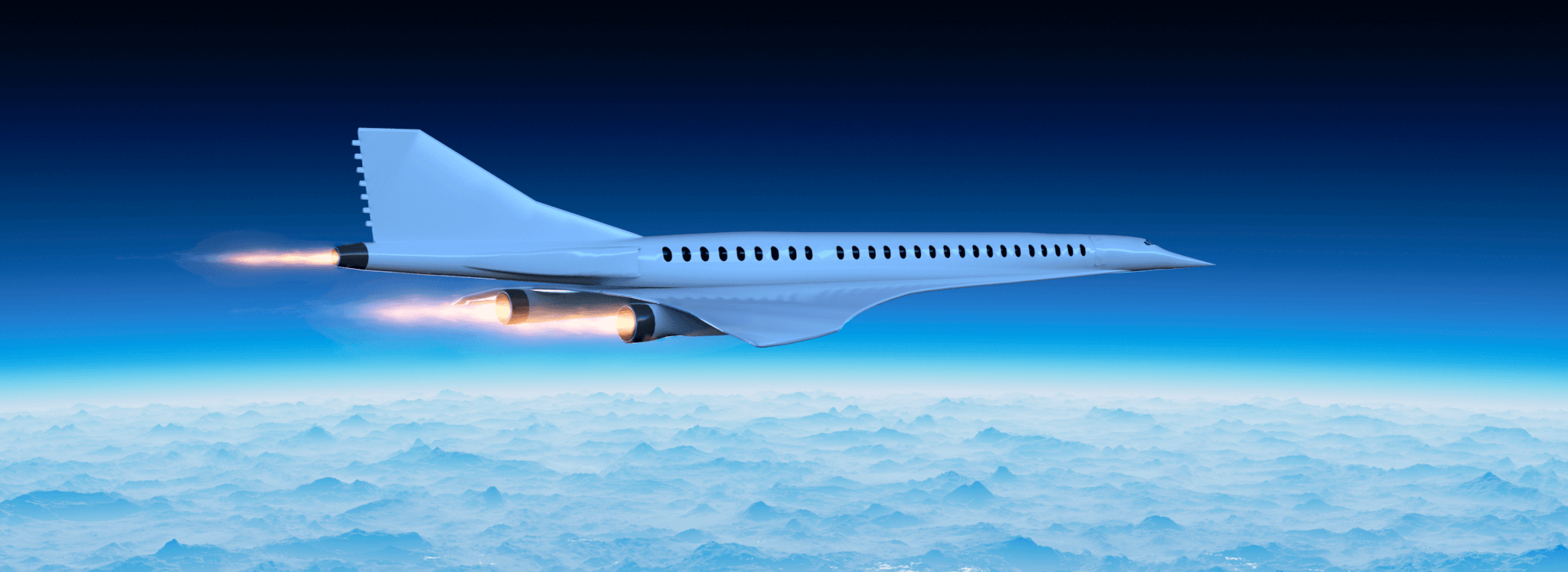

The aviation industry has started responding to increased pressure from consumers and governments to slash carbon emissions. In October 2021, at the International Air Transport Association (IATA) General Assembly in Boston, global airlines committed to net-zero aviation by 2050. Meanwhile, in February 2022, the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) finalized its own net-zero roadmap while simultaneously debating a separate but related issue: efforts to revive supersonic transport aircraft (SSTs). We believe that the ICAO should focus on proven methods for reducing the climate impacts of aviation, rather than using valuable time and funding to explore supersonics.

Not only are the twin goals of zero-emission aviation and supersonic aircraft nearly impossible to reconcile, supersonics pose a threat of an outsized emissions impact with questionable benefits.

Flying faster than the speed of sound is inherently energy-intensive, in part because supersonics use powerful, narrow engines to produce the high thrust needed to break the sound barrier. Due to this, supersonics burn an astonishing amount of fuel—between four and nine times more fuel per seat kilometer than subsonics (which account for all aircraft currently in commercial operation), according to an MIT report for NASA.

SAFs and supersonics: not a viable solution

Nonetheless, proponents of supersonics argue that sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) can help reduce the emissions produced by SSTs. SAFs can be used in today’s aircraft at up to 50% blends and are energy-dense enough to power long-haul and high-speed flights. But SAFs remain expensive — two to five times that of fossil jet fuel — and rare, comprising only 0.05% of the global jet fuel supply in 2020. Additionally, SAFs generated from edible crops can drive tropical deforestation when new land is cultivated to replace lost food.

A recent study by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a ClimateWorks Foundation grantee, explores whether SAFs can help reconcile the twin goals of zero-emission aviation and supersonic aircraft. Supported by the Aspen Institute and MIT’s Laboratory for Aviation and the Environment (LAE), the study models the economics, operations, and emissions of new supersonic aircraft operated on both a conventional “Jet A” fossil fuel and a synthetic “e-kerosene” generated from renewable electricity.

The ICCT/MIT report concludes that using SAFs in supersonics is not a viable solution. As a member of the International Coalition for Sustainable Aviation (ICSA), a network of NGOs representing civil society at ICAO, ICCT believes that SSTs should meet the same noise, air pollution, and CO2 standards as subsonic aircraft.

This approach will help ensure there is no net increase in noise or emissions due to the reintroduction of supersonic aircraft and is consistent with the industry’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. Notably, ICAO has begun to heed that call, moving at its most recent meeting to require supersonic aircraft to meet the same airport noise standards as today’s subsonic aircraft.

Philanthropy can help put aviation on a net-zero trajectory

ClimateWorks Foundation has been a strong supporter of ICCT and other ICSA members for over a decade. In addition to supporting ICAO research and engagement, ClimateWorks and our partners are working to put the aviation industry on a trajectory for net-zero emissions by 2050 by directing investments toward truly sustainable flights, reducing travel, and increasing supply while decreasing the cost of new fuels and technologies. The philanthropic community can advocate for these solutions over supersonic aircraft development, through the following approaches:

- International levers: Continued support for advocacy to the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO) environmental committee, while pursuing national-level action on the reduction of aviation emissions.

- Domestic levers: Advocacy for national, sub-national, and regional policies to curb aviation emissions, such as ReFuel EU, are key in driving near-team action and momentum towards greater international commitments.

- Demand levers: Doubling efforts to curb and manage the demand side of aviation through efforts such as corporate engagement to lower their flying footprint is another key pillar to support a race to decarbonize the aviation sector.

To learn more about this work, explore the International Council on Clean Transportation’s study and follow along as ClimateWorks continues to expand our aviation portfolio.

Blog updated on July 6th, 2022 to reflect ongoing research on supersonic emissions at ICAO.

In the past year, public and private funders have mobilized more than $6 billion for carbon dioxide removal (CDR), building the momentum needed to remove 5-16 gigatons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere annually and curb climate change. The movement is poised to accelerate after the April 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group III report identified CDR as an essential climate solution.

Recent weeks have seen a wave of announcements from the private sector for landmark investments in CDR. Days after the release of the IPCC Working Group III Report, Climeworks, a Swiss direct air capture startup, announced $650 million in new funding. Frontier, which has successfully scaled other public goods, including vaccines, committed $925 million to advance carbon removal on the heels of this announcement. Shortly after Frontier’s announcement, Lowercarbon Capital announced a $350 million venture fund to invest in carbon dioxide removal startups. Finally, on Earth Day 2022, XPRIZE identified finalists for the $100 million carbon removal competition, including several scientists previously supported by ClimateWorks who are now taking their science from the lab to the market.

These private sector funding efforts — representing the second and third largest removal investments ever — came amid the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) announcement that it will invest $14 million to advance direct air capture using waste heat, rather than relying on renewable energy alone. The DOE announcement is just the latest in a series of announcements from Congress and the Biden administration that total nearly $5 billion in new public support for carbon removal. (These include $1 billion in cumulative Congressional appropriations for carbon removal and $3.5 billion to build direct air capture (DAC) facilities in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act).

Laying the groundwork for CDR growth

While these headlines are extraordinary, they follow years of philanthropic work to help advance a portfolio of carbon removal approaches, ranging from forests to fans that remove and lock carbon dioxide away for a long time or convert it into clean alternatives such as jet fuel to power long-distance aviation. ClimateWorks and our partners have had the opportunity to help build the field of CDR philanthropy. For example, several years ago, ClimateWorks seeded the concept of corporate carbon dioxide procurement with a grant to the World Resources Institute (WRI) to engage major carbon removal purchasers. And ClimateWorks provided support for the peer-reviewed journal article on which the DOE’s recent $14 million announcement was based.

Today, ClimateWorks CDR program alumni work at companies ranging from Meta to Microsoft to deploy carbon removal. Recently, long-time ClimateWorks advisor Etosha Cave raised $57 million for Twelve, a startup that removes carbon dioxide from the air and recycles it into carbon-neutral jet fuel and other clean materials. Other previous program grantees are working with the U.S. federal government at the Departments of Energy, the Department of Interior, and the Department of Transportation.

Philanthropy’s continued involvement is key in ensuring that scaling efforts are grounded in scientifically rigorous and socially responsible ways. Additionally, philanthropic support can provide an unbiased evaluation of carbon removal opportunities and challenges — and help inform decisions to select removal approaches that have real climate benefits.

Philanthropy is crucial in scaling CDR responsibly

CDR is an essential climate solution. But as with any technological intervention, it must be scaled safely and responsibly. Philanthropic investment and involvement remain a key part of ensuring the ethical and strategic expansion of the field. Here’s how ClimateWorks is working with philanthropy on the responsible scaling of carbon dioxide removal solutions:

- Help steer carbon dioxide removal away from fossil fuel interests, which could attempt to co-opt this critical emerging field. For Climateworks, this has involved committing to never support the scaling of carbon removal via fossil fuels, opposing the use of removed carbon dioxide for fossil fuel production, and avoiding the use of carbon removal as offsets for abatable emissions. We are making grants to support the use of carbon removal to de-fossilize sectors such as long-haul aviation. In the process, this prevents the conversion of farms and forests into jet fuel, as some sustainable aviation fuels are made from trees or crops. Making aviation fuel from legacy carbon dioxide pollution in the sky has shown to have enormous air quality benefits, especially for frontline communities.

- Seed scientific research on ocean carbon dioxide removal. While the private sector races to deploy certain approaches to remove carbon from seawater, we’re working with philanthropy to support careful research to ensure that it produces broader climate benefits. Philanthropy is also supporting scientists who are working to answer key questions such as whether ocean CDR approaches are scalable, durable, safe, and responsible.

- Bolster efforts to ensure that the deployment of CDR technologies is just and equitable. Increasingly, the philanthropic sector has acknowledged the need to consider the implications of CDR efforts on frontline communities. In 2018, ClimateWorks launched the first philanthropic effort to make grants focused on advancing environmental justice as it relates to carbon removal and has supported organizations around the world — for example, by helping Carbon 180 create their Environmental Justice Initiative.

- Support the development of monitoring and verification methods for CDR projects. Currently, there is limited research on the governance and responsible deployment of carbon dioxide removal. To that end, the IPCC report recommends accelerated research, development, and demonstration of CDR projects; improved tools for risk assessment and management; and targeted incentives and development of agreed methods for measurement, reporting, and verification. At the moment, most private sector-led carbon removal initiatives do not address the need for better monitoring and verification methods. Philanthropy can and should step up to fill this key gap — and ClimateWorks will continue its commitment to improving monitoring and verification for CDR.

The time to scale is now

Years of groundwork have made possible the momentum for CDR that is evident today. With the private and public sectors mobilizing, now is the time for philanthropy to scale CDR funding and steer that momentum toward greater impact.

Scaling CDR will require both buyer ambition and increased research and deployment funding to drive down costs. And it will require wider acceptance and adoption of CDR efforts. To help unlock additional public funding and provide a roadmap for research, ClimateWorks sponsored a recent National Academies study that recommended a $2.5 billion investment to better understand the tradeoffs inherent in ocean carbon removal. Increased and aligned philanthropic funding in this area could create scale-up conditions to help ensure that carbon dioxide removal remains a public good and delivers meaningful climate benefits.

Carbon removal only constituted $50 million of the roughly $1.3 billion average annual climate-related giving by foundations from 2016 to 2020, according to a ClimateWorks study. Although philanthropic funding for scaling carbon dioxide removal has been modest when compared with billions in funding from the public and private sectors, philanthropy has played and continues to play an outsized role in helping to ensure carbon removal efforts scale safely, equitably, and effectively.

The recent public and private funding of over $6 billion is certainly worth celebrating and indicative of rising interest in the field, but there is much more work to be done. Keeping warming below 1.5°C would require a 20-fold funding increase in CDR solutions by 2030 combined with ambitious decarbonization, according to a new report by the Energy Transitions Commission.

The momentum for CDR is growing. It’s time for philanthropy to increase its engagement with the movement, coordinate and partner with governments and the private sector, and activate the funding needed to ethically and strategically scale CDR to reach its full potential as a key tool in ending the climate crisis.

To learn more, read about ClimateWorks’ CDR Program and follow along as ClimateWorks continues to expand its CDR work.

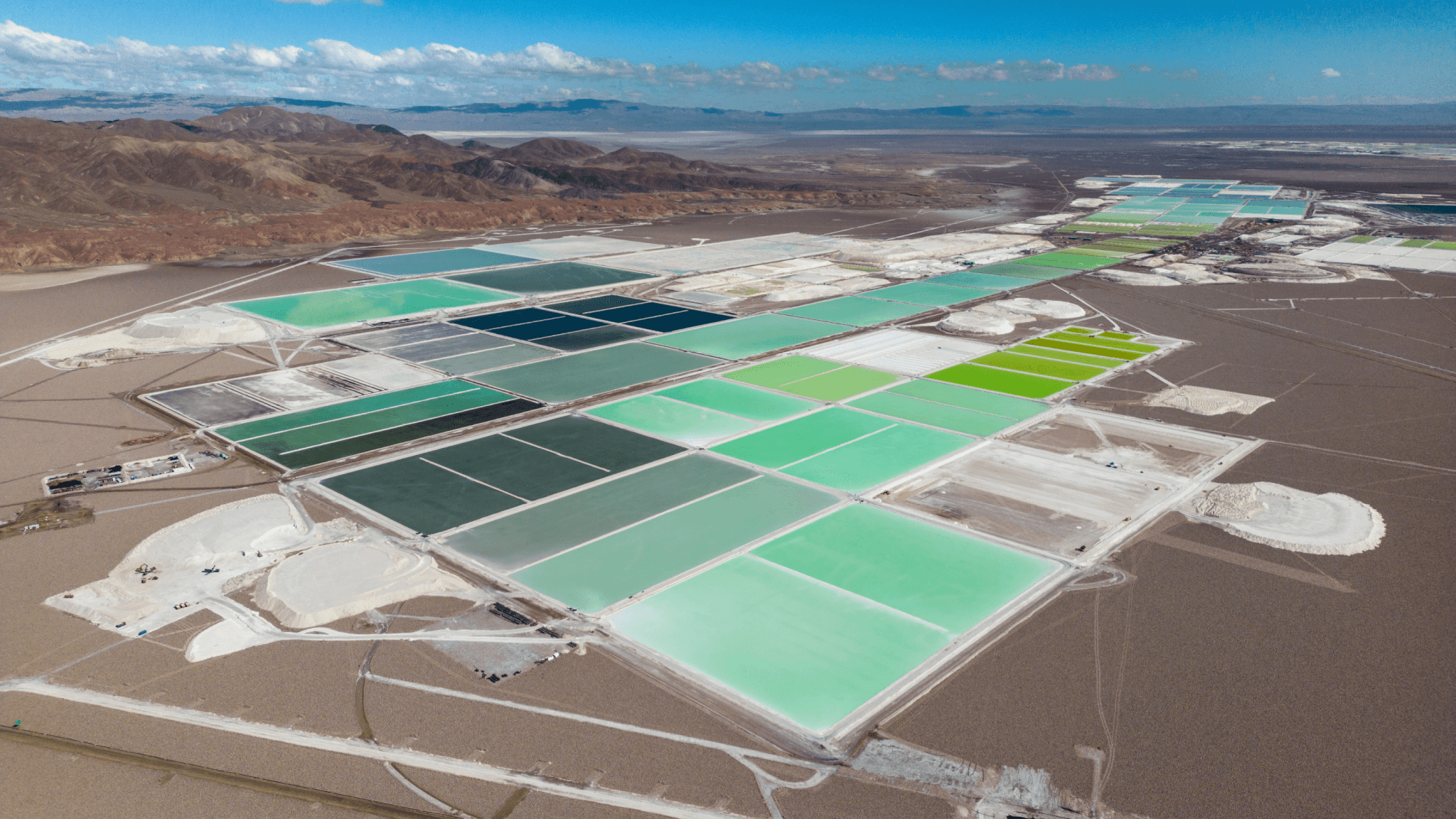

Transitioning to clean energy is a pressing global priority for securing a safe climate. Transportation is a major lever for change because the sector accounts for over 20% of global energy sector emissions and is a growing consumer of the minerals that clean energy technology requires. That’s why last month marked a major milestone as the European Parliament came out in support of the world’s first draft law to advance battery sustainability.

The proposal would require batteries produced or sold in the EU to comply with new social and environmental standards and checks to see if their raw materials are responsibly sourced. Many in the NGO community celebrated this – not only because the legislative measure crossed an important legal hurdle in the EU, but because the law will have a positive impact on supply chains worldwide, at a time when the demand is growing for minerals needed to shift away from fossil fuels.

Partners uniting for critical mineral responsibility

Responsible material sourcing for the energy transition touches many sectors and issues. Back in 2019, battery minerals emerged as a key area of collaboration for advocates and researchers across the EU and U.S., most notably through a convening and subsequent report produced by the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at UC Berkeley School of Law. At that time, Europe’s leading clean transportation campaign group, Transport & Environment (T&E), looked into the supply chains of cobalt for electric vehicles and found that the automotive industry was buying the raw material from just a handful of miners and refiners. The results illuminated that mandating environmental and social compliance on electric vehicles batteries could have potentially significant impact on the ground.

Earthworks, a leading NGO that stands for clean air, water and land, healthy communities, and corporate accountability has been focused on the mining impacts of clean energy for many years. In collaboration with The Institute for Sustainable Futures (ISF) at the University of Technology Sydney they released a 2019 report on Responsible Minerals Sourcing for Renewable Energy, which in turn supported advocacy to the World Bank by 50 organizations. By November 2021, momentum grew to 175 organizations call for more circular and demand-side solutions through the Declaration on Mining and the Energy Transition for COP26.

The EU battery regulation and the horizontal due diligence law are groundbreaking in the sense that they will provide the means for accountability, transparency, and human rights considerations throughout value chains.

In 2021, shortly after the sustainable battery law was drafted by the European Commission, T&E joined forces with Amnesty International to step up advocacy for the due diligence aspect of the battery law. This collaboration grew from their foundational research calling attention to the human rights violations surrounding cobalt extraction. With Amnesty’s expertise on human rights and T&E’s knowledge of the automotive sector and environmental campaigning, the two NGOs managed to get support from members of the European Parliament to publicly back stronger rules.

“This is an encouraging step in the right direction by the European Parliament” shared Richard Kent, researcher on human rights and the energy transition at Amnesty International Secretariat. “Batteries are central to the energy transition, and ensuring they are free from human rights abuse and environmental harm must be a top priority for lawmakers in the EU. Respecting frontline and Indigenous communities’ rights and livelihoods must be respected at all costs. Having strict due diligence requirements on the extraction and processing of key battery metals can help safeguard these rights, and will set a strong precedent for regulation elsewhere.”

Over the course of the Parliamentary review, new partners stepped in with additional pressure to support the law. Cultural Survival, which advances Indigenous Peoples’ rights and cultures worldwide, participated in advocacy for inclusion of Free Prior and Informed Consent in the law, with a recent visit to the European Parliament grounds. Galina Angarova, Executive Director, shares that “There is growing evidence that Indigenous Peoples’ land and territories and mining for transition minerals tremendously overlap globally…. The two pieces of legislation — the EU battery regulation and the horizontal due diligence law — are groundbreaking in the sense that they will provide the means for accountability, transparency, and human rights considerations throughout value chains. We joined our partners in Brussels with a goal to meet with Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) and advocate for inclusion of references to Indigenous Peoples, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in these laws to ensure that the rights of Indigenous Peoples are secured during the transition to the green economy.”

Angarova cites the scale of the market as driving significant impact: “a lot that is happening in the European Union is going to dictate how the raw materials for batteries are going to be sourced, processed and traded globally. Knowing that Indigenous peoples’ lands and territories are the primary targets for extraction, it was critically important for us to deliver messages to the parliamentarians about the direct impacts of transition mineral mining on Indigenous communities.”

Partners at Earthworks also offered advocacy support. “The EU is poised to set a new high standard for respecting human rights and environmental protection in global extractive industries while maximizing recycling for transportation supply chains. Similar laws are needed in more regions to ensure the rights of mining-affected and Indigenous communities are safeguarded,” said Vuyisile Ncube, Earthworks’ Making Clean Energy Clean Advocate.

Similar laws are needed in more regions to ensure the rights of mining-affected and Indigenous communities are safeguarded

The final text still needs to be negotiated and agreed upon by the European Parliament and by EU countries. By bringing together research and human rights advocacy, our partners have shown that it is critical that rules on due diligence, recycling, and carbon footprint are implemented as soon as possible to contribute to a responsible clean energy transition. Many other groups have participated and commented on the battery law.

Alex Keynes, clean vehicles manager at T&E, said that “this puts Europe firmly on the path to a sustainable zero-emissions future. The batteries that replace the burning of oil will need to be produced with green energy, made from responsibly sourced metals and fully recycled at the end of their life. Europe’s battery factories are being set up today, so any delays to recycling targets and checks on responsibly sourced materials are indefensible.”

Philanthropic support and way forward

While this is a significant step towards making batteries more sustainable, we still have a long way to go. In partnership with European Climate Foundation, Energy Foundation, and the 11th Hour Project, ClimateWorks continues to support action at this critical intersection. The EU Battery Law is just the first step. Philanthropic partners across various areas of work are coming together to push for regulations on recycling, responsible sourcing, and emissions caps — while simultaneously encouraging business leadership from automakers and all other manufacturers that use lithium-ion batteries. As highlighted in our most recent blog, much more action can be taken to preserve human rights, increase recycling and circularity, and support a just transition.

Our oceans have soaked up more than one-third of man-made carbon dioxide emissions since the industrial revolution. Yet increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the ocean are making seawater warmer and more acidic, causing devastation to coastal and marine ecosystems.

The vast majority of ocean-related philanthropic funding currently supports the conservation and restoration of marine habitats. While important, these measures are only one part of the solution and are insufficient to protect against climate stressors on their own. To help keep climate change in check, we must support solutions that both improve ocean health and aid in the ocean’s capacity to absorb and store carbon dioxide.

On this Earth Day, we reflect on how to make the ocean our ally in fighting climate change and restoring marine ecosystem health.

Climate change impacts are hurting marine ecosystems and vulnerable communities

Greenhouse gas emissions have led to unprecedented levels of ocean warming and acidification. Surface seawater has warmed by nearly 0.88° C since the last century, exacerbating extreme regional ocean warming called marine heatwaves, which have become more frequent, longer, and hotter. Over 57% of the ocean has experienced marine heatwaves compared to just 2% a century ago. Marine heatwaves are associated with mass mortality events for sensitive marine ecosystems, including kelp forests, seagrass, mangroves, and coral reefs, as well as economically important species such as lobster, snow crab, and scallops. Higher water temperatures associated with marine heatwaves can also exacerbate extreme weather events such as tropical storms and hurricanes, and disrupt the water cycle, making floods, droughts, and wildfires on land more commonplace.

Seawater acidity has increased by approximately 30% since pre-industrial levels as the ocean absorbs more CO2 due to higher concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Acidic water inhibits the shell formation of organisms including shellfish and has killed over half of the coral reefs globally, disrupting the well-being of a quarter of marine life. Local interventions to prevent further bleaching of coral reefs can only do so much while the global drivers of the problem continue to worsen.

Ocean ecosystems provide food, energy, tourism, and services such as climate and weather regulation. This means that declining ocean health is a major risk to our economies and societies. Impacts on marine ecosystems severely disrupt the marine food chain, leading to collapses of regional fisheries and aquaculture. These impacts make coastal communities more vulnerable.

Over 3 billion people around the world rely on the ocean as a major food source and many fishers’ economic livelihoods are threatened worldwide. Many of these communities, including developing island nations and indigenous communities, are not large polluters themselves, yet they are the ones suffering the most severe impacts. The recent IPCC Working Group II report recognizes the important interdependencies between climate, ecosystems, biodiversity, and human societies, and recommends steps to reduce carbon emissions, adapt to a changing climate, and remove excess carbon dioxide to prevent imminent and irreversible impacts on our ocean and coastal regions.

Making the ocean an ally in our fight against climate change

Ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods enhance the ocean’s natural ability to safely remove and sequester carbon dioxide while also helping to improve ocean health and increase the resilience of marine ecosystems against climate change impacts. Seaweed cultivation and ocean alkalinity enhancement, both highlighted in the recent National Academies report, are just two examples of a set of approaches being explored by ClimateWorks. CDR approaches have varying levels of permanence and potential for removing and storing CO2. Thus, the world will benefit from a diverse portfolio of carbon removal strategies to ensure we meet climate goals.

Seaweed is grown virtually all over the world and has been harvested and consumed by humans for centuries. Seaweed cultivation does not require land or fresh water, and it can be used for biofuels, animal feed, and bioremediation. In addition to displacing emission-intensive products, seaweed can be buried or exported to the deep ocean after sequestering CO2. It has the potential to remove around 0.03-0.1 Gt CO2 globally.

Today, the majority of seaweed is grown off the coasts of Asia and East Africa, though the industry is emerging in Europe, the Americas, and Oceania. Indigenous groups working to reemphasize the ability of seaweed to support food sovereignty, climate resilience, and connections to tradition are playing an increasingly important role in developing seaweed cultivation approaches. Supporting the use of indigenous knowledge and practices is a key opportunity in this space.

Seaweed cultivation as an approach, still requires improved measurement and verification of the CO2 sequestered. Another major barrier to scale is helping farmers navigate the permitting landscape, which could easily take years and incur significant legal costs. Philanthropy is uniquely positioned to support and facilitate the convening and co-creation process with policymakers, scientists, farmers, and communities in getting this field to scale rapidly and responsibly.

Ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) reduces ocean acidification by imitating naturally occurring processes where alkaline rocks are washed into the ocean. OAE has the potential to remove between 0.1-1 Gt CO2 per year, and the ability to sequester CO2 for centuries, making it one of the most effective and durable CO2 removal approaches. In addition to addressing climate change, OAE can also protect nearby coral reefs and shellfish by reducing seawater acidity. However, this approach is still nascent and is just beginning to be tested on a very small scale. More questions need to be answered, such as the efficiency and effectiveness of CO2 sequestration and the impact of additional alkalinity on marine creatures. Philanthropy can help catalyze significant research funding from the public and private sectors and support the participation of local communities throughout.

Key recommendations for philanthropy

Up to this point, ocean-related philanthropy funding has focused primarily on restoration and conservation efforts. Funding is needed to address both the symptoms and the cause of ocean climate impacts. While habitat protection and conservation provide significant benefits, the IPCC is clear that protected areas in their current form “do not confer resilience against ocean warming and heatwaves.” Similarly, the IPCC also states, “the effectiveness of nature-based solutions declines with warming; conservation and restoration alone will be insufficient to protect coral reefs beyond 2030.”

From 2010 to 2020, philanthropic support for marine-related issues totaled roughly $8.5 billion. Of this, about one-third went towards habitat protection and addressing ocean plastic pollution, while only 2% went to climate and energy issues, mostly for shipping decarbonization and offshore renewables. ClimateWorks data estimates roughly $7 million per year is currently going towards exploring how to safely harness the ocean’s ability to remove CO2. This is nowhere near the National Academies of Sciences’ recommendation of $2.5 billion for ocean-based CO2 removal research over the next 10 years.

Philanthropy has played a key role in catalyzing support to deepen the understanding of the ocean-climate nexus. Funders must continue to promote and support critical research needed to quickly scale and deploy solutions, and facilitate community participation so this can be done responsibly.

Philanthropy is best positioned to:

- Promote literacy of the ocean-climate nexus: increase awareness of climate change’s impacts on the ocean and the ocean’s role in addressing climate change.

- Catalyze funding for science and research: mobilize public and private sector funding through policy intervention and investments towards key research questions and areas, such as those identified by the National Academies report.

- Support ecosystem building around responsible research, co-creation, and knowledge sharing: promote transparency of science, responsible research, and local communities’ co-creation of ocean-based carbon removal approaches. Where possible, support indigenous knowledge and practices.

The bottom line

The recent IPCC Working Group III report unequivocally states that continued high rates of greenhouse gas emissions have made it necessary to reduce emissions to zero and remove gigatons of CO2 to limit global warming to 1.5° C. Climate change today is hurting our ocean and communities, and additional warming will lead to the irreversible loss of marine creatures, ecosystems, and livelihoods at a much greater scale. Most ocean philanthropy today addresses the symptom of climate impacts but more support is needed to address the root cause of climate change by removing excess CO2 from the ocean and the air. While the ocean’s potential as a tool in the climate fight is enormous, research and development around ocean CDR are still relatively new. We need to scope and test a diverse set of solutions to both reduce emissions and remove CO2 quickly. To do this, philanthropy has an important and unique role to play and must act decisively and responsibly starting today.

When an aircraft burns jet fuel, it releases not only carbon dioxide (CO2) but also creates other byproducts including nitrogen oxides (NOx), water vapor, soot, and aerosols which, at altitude, react with the atmosphere and contribute substantially to global warming.

In November 2020, the European Commission published a thorough and scientifically authoritative report by the European Aviation Safety Authority (EASA) fully dedicated to these non-CO2 effects of aviation. It confirms that non-CO2 effects make up two-thirds of aviation’s climate impact.

One of aviation’s main non-CO2 effects is linked to contrails, with contrail cirrus alone accounting for up to 57% of the total impact. These are long cloudy strips that form when moisture in ice-saturated air freezes around soot particles released by burning jet fuel. Contrails can form cirrus clouds that trap heat radiating from the earth’s surface, especially at night. The chemical composition of jet fuel, in particular the level of aromatics (molecules that form soot during combustion), has a significant effect on the level of contrail formation and therefore the level of non-CO2 climate effects from flying.

ClimateWorks is partnering with Transport & Environment, our long-standing grantee, to explore the impact of non-CO2 emissions in aviation and offer recommendations to mitigate their effects on the climate.

Ways to tackle non-CO2 effects now

Over the last decade, there has been no formal attempt by policymakers to mitigate the effects of non-CO2 chemicals in the atmosphere. Most recently, the European Commission missed a golden opportunity to include aviation non-CO2 mitigation measures in its “Fit for 55” package proposal, the EU’s plan for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030. This is especially disappointing because two clear solutions have been highlighted by the EASA report, both aimed at reducing persistent contrail formation: cleaner-burning fuels with fewer aromatics and trajectory optimization (i.e., the use of alternative flight paths to avoid areas of airspace prone to persistent contrail formation).

Non-CO2 effects make up two-thirds of aviation’s climate impact.

Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAFs) have an aromatic content (often 0%) lower than the average aromatic content of fossil fuels. As SAF production slowly increases, parallel action needs to ramp up to reduce the aromatic content of the fossil jet fuel which can be achieved through adding extra hydrogen to the fuel. To address this urgent issue, policymakers must create an impact assessment outlining several policy options and technological solutions, and then write a legislative text on optimizing the aromatic content of jet fuel. For instance, the European Commission can pursue this process through its ReFuelEU Aviation policy, which aims at providing better fuel for aviation. To learn more about Transport & Environment’s recommendations for these policy changes in Europe, see their latest briefing.

Trajectory optimization is another way to reduce aviation’s non-CO2 effects. Real-life research projects that have already been conducted in Japan and the UK have demonstrated that partial mitigation of around 40% of contrails would come at a negligible cost in terms of flight time. It is, therefore, crucial to support projects like these and further explore paths to accelerating trajectory optimization. At the same time, in all mitigation options, it is essential to consider the trade-offs. For example, potentially increased CO2 emissions in the case of aircraft diverting their routes — we don’t want the cure to become worse than the disease.

Flying forward

This is a significant year for sustainable aviation in the European Union and beyond. With the EU’s “Fit for 55” package being negotiated in Brussels, this is an ideal time to start mitigating aviation’s non-CO2 effects and leading by example for other regions to follow suit. This should take the form of swift and meaningful policy action aided by thorough research, institutional accountability, technological solutions, and a reduction in post-Covid-19 pandemic demand. In this spirit, Transport & Environment brought together industry, policymakers, and researchers for its inaugural aviation non-CO2 summit in March 2022 to tackle this important issue and will continue to advance the conversation. The participating stakeholders agreed that it is important to conduct more research on this topic, but there are also ways that we can and must act now to reduce the non-CO2 effects of aviation through policy and technology. We need bold and decisive action to mitigate the long-term effects of aviation on our climate.

Multilateral development banks are key institutions for financing the climate transition – but are they doing enough to drive zero-emission vehicle adoption?

Reducing emissions from transportation is an urgent global priority, as underscored in the latest UN IPCC report on climate mitigation. However the solutions, including battery electric transportation, are not yet accessible in many regions of the world. We cannot solve the challenge of transport emissions by creating a situation where only the wealthiest countries have access to electric mobility and the resources to design efficient, safe, climate-friendly transit systems. A vast majority of the world’s population growth by 2050 is forecast to take place in the Global South, and for those economies to grow sustainably, it is critical that transport systems shift from a reliance on fossil-fueled internal combustion engines (ICE) to zero emissions vehicles (ZEV).

Unfortunately, the very institutions tasked with helping countries develop in a sustainable and climate friendly manner, the Multilateral Development Banks (the Banks), continue to perpetuate the assumption that developing countries are not ready for electric transportation. For example, our partners at the Bank Information Center recently uncovered that of the World Bank’s public sector transport financing, just 2% is for ZEV projects like electric buses and charging stations, while 68% is for projects that support fossil fuel-dependent vehicles and infrastructure, including refineries and petrol stations.

Of the World Bank’s public sector transport financing, just 2% is for ZEV projects like electric buses and charging stations, while 68% is for projects that support fossil fuel-dependent vehicles and infrastructure, including refineries and petrol stations.

Simply put, these investments lock in carbon emissions and unhealthy air pollution that we cannot afford within the narrowing window of time to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Here is where philanthropy has the opportunity to change the course and galvanize public financing toward strategic climate action. ClimateWorks Foundation’s Drive Electric Campaign and Finance Program are working together to encourage the Banks to align their portfolios with the Paris Agreement by phasing out investments in dirty ICE, and increasing investments in clean and affordable ZEV systems.

Development banks can mobilize climate-smart capital

The Banks were originally founded with a clear development mandate to support the economic development and growth across their recipient countries. However, in response to the climate crisis, they are increasing their capital allocation towards climate-smart investments. For example, in 2019, the Banks announced their annual climate action targets for 2025: at least $65 billion of climate finance in total, with $50 billion for developing countries; and unlocking additional investment of $110 billion, including mobilization of $40 billion in private investment.

Since the Paris climate conference, the Banks have rhetorically embraced the climate imperative of transportation decarbonization. The World Bank’s climate action plan speaks explicitly about the need to shift to ZEVs, citing the need for “aggressive measures.” Unfortunately, this plan has not led to any tangible shift in their investment approach, as evidenced by how little finance they have provided to close the massive investment gap needed to support ZEVs in emerging economies. Most of the Banks continue to prioritize their development mandate above their climate goals. This investment approach locks in dirty mobility options and impedes the potential for technology leapfrogging to ZEVs in developing countries.

But options to shift this trajectory are readily available to the Banks. One overlooked opportunity for ZEV investments is the potential to leverage funding from global climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF). These funds help de-risk Multilateral Development Bank investments into climate mitigation and adaptation projects. This arrangement has been quite successful for many years in the renewable energy sector, but the Banks have been hesitant to develop ZEV projects given the perceived risk and uncertainty.

Most of the Banks continue to prioritize their development mandate above their climate goals.

One of only a few examples researchers were able to find of zero-emission transportation Bank investments was the Green Bus Rapid Transit Karachi project, jointly funded by the Asian Development Bank and GCF, which aims to build a zero-emissions BRT system in Pakistan. The GCF’s concessional financing allows the project to overcome transactional barriers, close the financial gap, and secure sufficient technical and managerial assistance, thereby unlocking investments from both MDBs themselves and other public and private funding sources. This project exemplifies the power of combining Bank and climate fund investments to support ZEV adoption.

Banks need to change gears and phase out polluting transport in favor of electric

We need more of these projects, because clean transportation is a win for climate and development. But research shows that the Banks are barely scratching the surface: the Bank Information Center team looked at active projects at the World Bank and found relatively little commitment to ZEVs. While the public sector arm of the World Bank spent $77 billion on projects involving ICE vehicles and infrastructure between 2017 and 2021, it spent less than $1 billion on projects involving ZEVs. For the International Finance Corporation, the private sector arm of the Bank, only one percent of total project financing went to projects supporting ZEVs.

For the Banks to show that they are serious about decarbonizing transport, they must commit to ending all investments for fossil fuel-dependent vehicles by 2025 (as dozens of countries around the world have done). This should be coupled with increased investments in ZEV systems and infrastructure and must include plans for sustainable and equitable minerals extraction and reuse for batteries as well as clean power generation to support charging infrastructure for electric cars, buses, and trucks. By making this shift, the Banks can play a critical role in creating a world in which everyone has access to transport infrastructure that is both climate-resilient and climate-friendly.

How these providers of public money invest is, inescapably, how they demonstrate commitments. Twenty-two organizations sent a letter to all the Banks in November 2021, asking them to end support for fossil fuel-powered road transportation by 2025. The letter also calls on MDBs to directly address poverty and development inequities by increasing access to transit and transport services for disadvantaged, marginalized, and mobility impaired peoples. While some MDBs have been open to dialogue, only the World Bank provided a specific reply to the November letter, in which it claimed “[o]ur portfolio is rapidly shifting toward low or zero-carbon transport solutions…” The Bank must back up this statement with clear benchmarks and timelines for phasing out ICE vehicle related investments.

For the Banks to show that they are serious about decarbonizing transport, they must commit to ending all investments for fossil fuel-dependent vehicles by 2025.

Financing electrified transport systems in time to secure a safe climate is an ambitious but feasible goal. We have the technology and the resources. The next step is galvanizing financial institutions to support the shift to clean transportation for everyone. Working collaboratively, ClimateWorks is leveraging our expertise in financial architecture and transportation to encourage ZEV investments in the Global South. To learn more about how we are supporting this shift check out the Drive Electric Campaign, supporting 100% zero emission transport for the entire world.

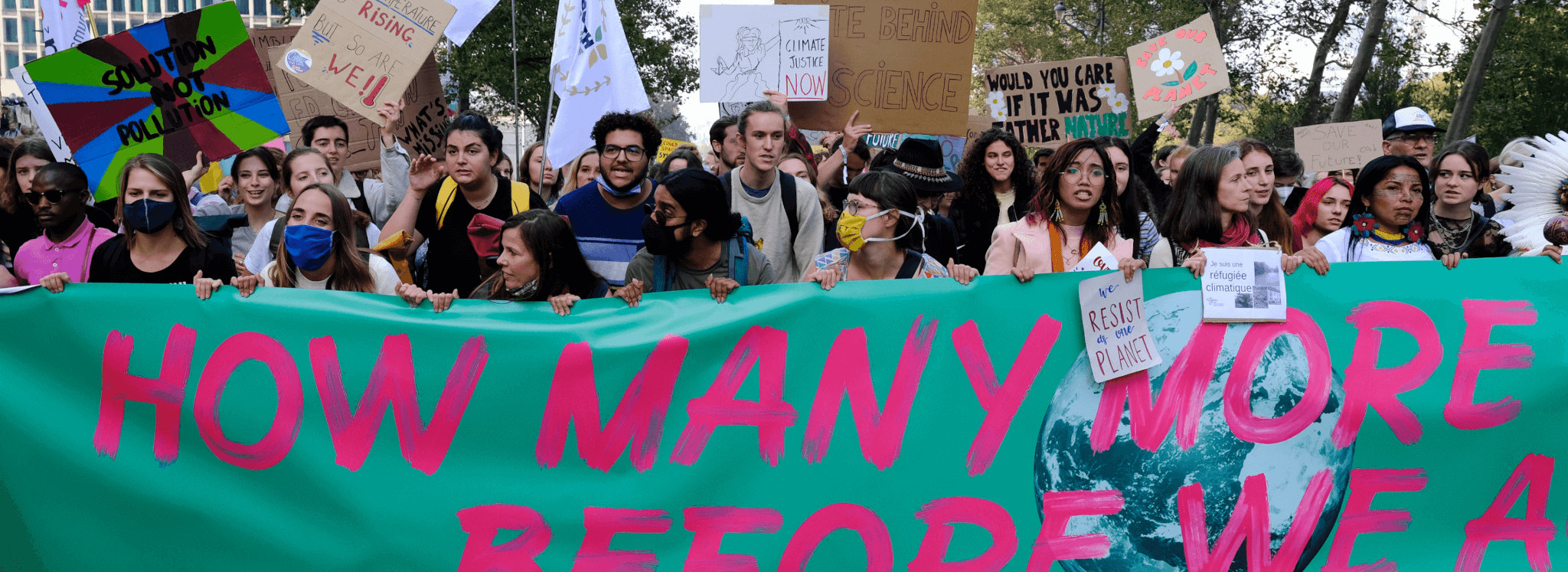

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has released the latest installment in its Sixth Assessment Report. The Working Group III (WGIII) report focuses on climate change mitigation and the policy, technological, and social levers we must urgently mobilize to keep the world below 1.5C of warming by the end of the century. It adds to the body of science the IPCC has released in this cycle – the latest science behind climate change (Working Group I report) released in August 2021 and the impacts of climate change, including limits of natural ecosystems and society to adapt to disastrous climate change impacts, (Working Group II report) released in February this year. The WGIII report lays out very starkly that if we miss the window to act on climate change over the next few years, we will no longer be able to stabilize the climate at under 1.5C of warming. As the WGI and WGII Reports bleakly highlighted, climate impacts are already affecting people on every continent of the world at just 1.1C of warming, so every fraction of a degree matters.

One of the main messages of the latest IPCC Report is that we need to urgently use all our tools to tackle the climate crisis, not just a few, and we must do so at scale. If we do, we can together shift onto a better path for the climate this decade before it is too late.

One of the main messages of the latest IPCC Report is that we need to urgently use all our tools to tackle the climate crisis, not just a few, and we must do so at scale.

To meet the Paris Agreement goals, governments and businesses need to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. The IPCC report shows that sustained emissions reductions are possible with supportive policies. At least 18 countries have sustained GHG emissions reductions in annual CO2 and GHG emissions for well over a decade. Many achieved these emissions reductions alongside sustained economic growth. This trend, both for consumption and production-based emissions, needs to be amplified and expanded to many more countries. A range of strategies enacted through policies can limit warming, including:

Electrify the global energy system with carbon-free energy and phase-out fossil fuel infrastructure.

The cost of renewables has fallen so precipitously that they have become the default economic choice for new power generation capacity. Scaling all forms of zero-carbon power generation can also benefit other sectors. Some of these technologies already exist, and some, like green hydrogen, need to be scaled rapidly.

Electrify all modes of transportation to slash emissions.

Powered by abundant renewable energy, electric transportation can eliminate over 90% of transport-related climate pollution and nearly all oil demand from road transport. It is an important part of a broader package, including a focus on compact urban design, public transport, and non-motorized transport.

Slash short-term super pollutants by 34% by 2030 instead of 2050.

Eight years ago, the IPCC targeted reducing methane by 34% by 2050. The latest report significantly moves up that deadline to 2030. The immediate reduction in methane, hydrofluorocarbons (F-gases), black carbon, and ground-level ozone can dramatically slow the rate of warming in the near term and offers a chance to meet net-zero emissions targets by 2050.

Address the climate finance gap immediately.

Rich countries are overdue in delivering on their promise of giving $100 billion per year in climate finance to less wealthy nations to help them mitigate and adapt to climate change. Without financing options, people living in the most vulnerable nations cannot adapt and will suffer the most.

Removing excess carbon from the atmosphere is essential to restoring the climate.

The IPCC report makes clear there are no pathways to 1.5C that don’t include carbon removal. Natural sinks as well as technologies that mimic nature will be needed and scaled to meet the challenge of removing legacy CO2 emissions. Natural sinks alone cannot solve the problem. For more on the IPCC’s findings on carbon removal, read here.

Embed sustainable development in transitions.

Inequitable decisions lead to resistance, and we cannot expect to scale low carbon transition solutions without embedding principles of equity and a just transition into decisions. If done well, bold climate action can boost jobs and income, lead to significant health benefits and more inclusive, sustained growth. But we also need to understand and manage any trade-offs.

Apply holistic approaches to reduce carbon in buildings.

Smarter building design and construction choices made today can reduce emissions for decades to come. The IPCC report offers a range of interventions to decarbonize the built environment across the building lifecycle, including retrofitting existing building stock, repurposing existing buildings, and using low-emission construction materials.

Build a circular economy.

We can strengthen policies and innovation around using materials more efficiently to reduce waste and emissions. This includes more materials recycling, especially in the industrial sector.

Gain large-scale emissions reductions from sustainable shifts in agriculture, forestry, and other land use.

The IPCC report underscores the untapped mitigation potential in this space. Measures such as sustainable forest management, reforestation, soil carbon management, sustainable crop and livestock management, and healthier diets can provide as much as 20%-30% of the emissions reductions needed to meet climate goals.

A rapid but orderly low-carbon transition can reduce risk globally. Government decisions about when and how to implement a national clean energy transition matter. It influences energy security and how nations react in times of calamity. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has underscored the massive dangers of continuing our addiction to oil and gas. By pursuing orderly, planned transitions to reaching net-zero targets by 2050, including immediate near-term action, countries can help avoid worst-case scenarios, enhance energy and food security, and reduce geopolitical and economic risks. There is a limit to how many times society can adapt to shocks, be it financial or energy, food, or extreme climate event related.

To help nations decarbonize their economies, central banks, governments, businesses, and civil society groups need robust economic analysis to better integrate the opportunities and costs of climate action and an understanding of the risks of inaction in their climate action frameworks. An integrated framework to assess the physical and transition risks stemming from the impacts of a warming world can help show the advantages of shifting to a low-carbon economy and how to avoid costly lock-in of fossil assets. We need to identify, categorize, calculate, and balance the associated societal, economic, and financial impacts of climate action and inaction and reflect that in country budgets, and economic and investment planning.

For the first time, the IPCC report recognizes that a rapid transition to a low-carbon economy will not be a drag on the economy, with the underlying models used for the assessment having reflected some of the latest rapidly falling costs of clean energy and other solutions which have increasingly made them cost-competitive with fossil fuel based power. Once the much larger costs of inaction are considered as well, and the dynamic opportunities of new innovations through a net-zero economy, many other analyses suggest the opportunity for a significant net benefit from bold climate action instead. The new IPCC report reflects an important first step in the economic modeling frameworks catching up with reality, but there is still more to be done.

Philanthropy is vital to increasing the pace and scale of climate action

The IPCC’s recommendations for climate change mitigation represent a huge step-change in how the community needs to work together to raise and deploy the resources and supportive policies and technologies needed to tackle the climate crisis. This is where philanthropy has been and must continue to play a critical role in catalyzing action at the scale and speed the world needs. Below are areas where philanthropy can substantially help to avoid a code red future.

- Cross-sectoral approach to integration of solutions — Achieving full mitigation means all stages—from production to consumption to transportation and disposal—have to be considered in addressing emissions, utilizing both supply and demand side measures in various sectors, as noted in the report. An example being food systems where philanthropy can support multi-disciplinary approaches to how one integrates innovative technology, energy use, biodiversity, human and ecosystem health and livelihood protection while solving for tradeoffs and synergies to achieve both climate and societal goals.

- Equitable and a just transition — The world can only win on climate if we ensure the major system-wide transformations needed actually work for people – as individuals, communities, and economies. Philanthropy is well positioned to support a diversified set of solutions that reflect social and economic justice by supporting people-led movements and ensuring the voices of the most vulnerable and underrepresented groups are heard.

- Transparency and accountability are essential building blocks for effective climate action, increasing ambition, and building international credibility. Philanthropic-led initiatives can drive accountability by helping stakeholders clearly understand where action is on track and where more effort is needed.

- International multi-stakeholder cooperation — Philanthropy is adept at bringing together relevant actors from governments, NGOs, businesses, people-led movements, and other civil society groups to foster radical collaborations and elevate new approaches that deliver results. The recent COP26 in Glasgow showcased a number of breakthroughs and new pledges, and we now have to deliver on them and hold ourselves accountable.

The best pathway to tackle the climate crisis is to accelerate an orderly transition to zero emissions, deploying all the levers we have available. We have the tools and solutions to cut emissions in half by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century. The IPCC report is clear: the primary barriers we face are not technical or economic, they are political. But with financing and better collaboration across governments, communities, businesses and philanthropy, we can keep the 1.5C goal in our sights.