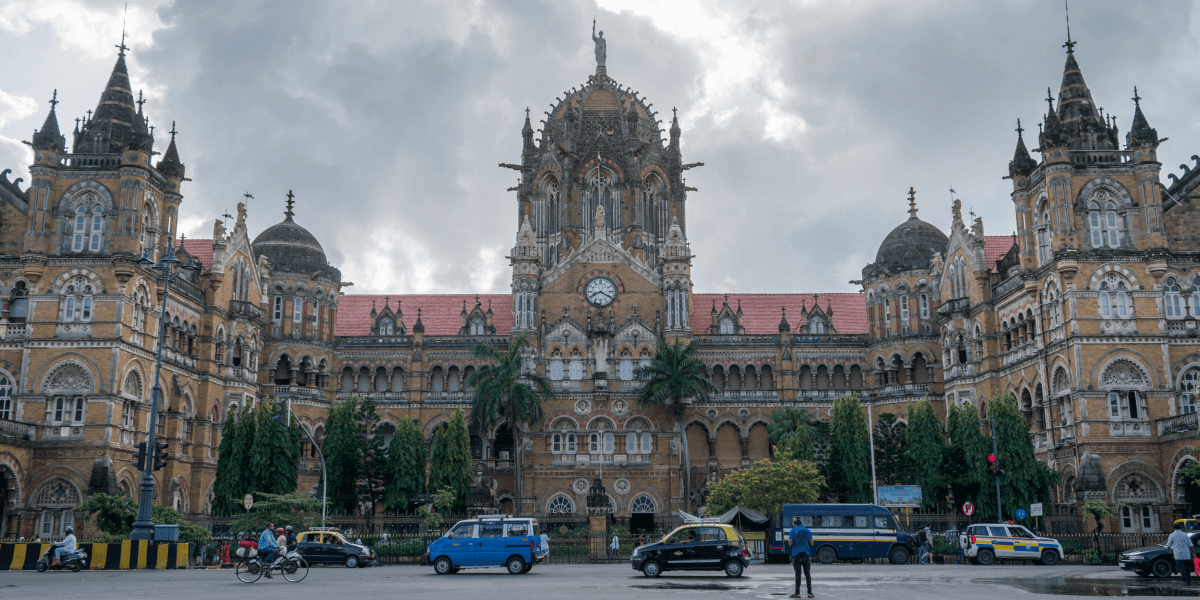

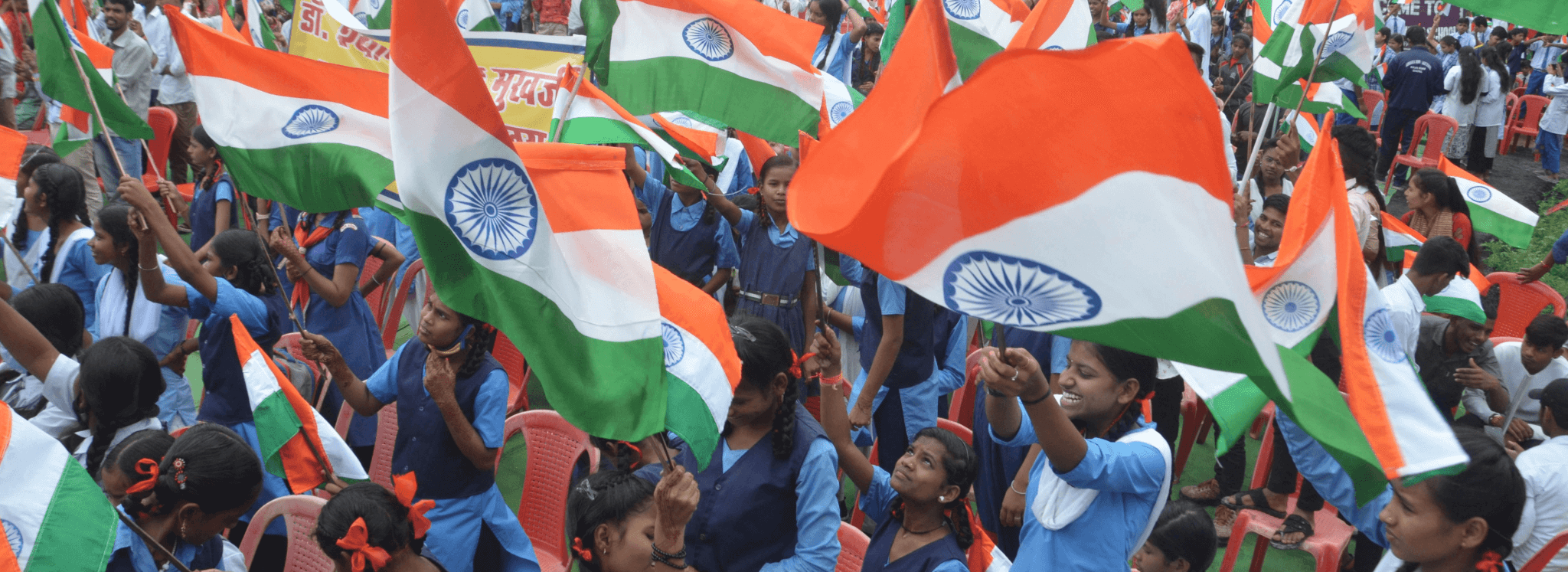

At the 2021 UN climate conference in Glasgow, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a lofty net-zero emissions target for India by 2070, significantly boosting the country’s climate profile in the lead-up to completing its landmark 75 years of independence dubbed India@75.

As part of the ambition, Prime Minister Modi committed to raising non-fossil-fuel-based energy capacity to 500GW, meeting 50% of energy requirements using renewables, reducing total projected carbon emissions by 1 billion tons, and decreasing the carbon intensity of the economy to less than 45% — all by 2030. India’s recently updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), a climate action plan that came out of the Paris Agreement, further cemented two of these goals by officially pledging to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 45% from the 2005 level and achieving 50% of cumulative electric power from non-fossil-fuel-based energy resources by 2030.

These climate actions have established India as one of the leading emerging markets to transition toward clean energy. This can be seen by the volume and pace of wind and solar construction, the rapid adoption of electric vehicles, a rapid expansion of renewables and battery manufacturing, and the country’s early-mover status on emerging clean technologies like green hydrogen.

While these energy transitions are key pillars of India’s efforts to mitigate adverse climate change impacts, an equally significant effort is the broader economic transformation that is underway. Spurred by shifting geopolitical fault lines and India’s own development imperatives, the country has elevated strengthening domestic manufacturing, creating local jobs, securing supply chains, and fortifying energy security as the cornerstones of its climate and clean energy actions. For India’s decarbonization journey to align with inclusive economic growth, the country must ramp up ongoing infrastructure reform and navigate the internal complexities of federal politics and land and labor systems, as well as the external challenges of securing low-cost transition finance.

With most recent estimates suggesting that India will need more than $17 trillion in investments to meet its net-zero goals, the moment for developed economies to come forward and support these efforts is overdue. Despite this shortfall, India is continuing to chart its own unique pathway that can provide learnings and templates for other emerging economies.

Transforming India’s energy and transportation sectors

India is among the world’s top five largest renewable energy producers and has received global recognition for its renewable energy deployment. In August 2021, India reached the commendable milestone of 100 GW of installed renewable energy capacity. Estimates show that India’s renewable energy sector grew at an annual rate of 17.5% between 2014 and 2019, during which the share of renewables in the country’s total energy mix increased from 6% to 10%. Thanks to favorable government policy, foreign direct investment in the renewable sector has risen steadily and amounted to a cumulative $10.81 billion between 2015 and 2022.

India’s ambitious targets and policy signals will continue to attract foreign and domestic investments in the sector and lay the groundwork for the country to emerge as a solar PV manufacturing hub. As a crucial step, the Production Linked Incentive funding scheme (PLI) introduced in 2021 incentivizes companies to set up solar module plants in India as well as electric vehicle or EV manufacturing. As manufacturing becomes increasingly cost-competitive, greater financial incentives and support could enable India to play a key role in diversifying supply chains. However, the country will have to bridge some challenges at the national and sub-national levels, including grid modernization and the improved financial health of utilities.

India is also rapidly moving towards transforming its mobility sector. By 2030, the government aims to have EV sales account for 30% of private cars, 70% of commercial vehicles, and 80% of two- and three-wheelers. In 2020, the central government announced the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (FAME India) to incentivize the adoption of EVs, extending the scheme until 2024.

In addition to R&D, subsidies, vehicle scrappage policies, and charging infrastructure, India also took big strategic steps toward developing a thriving domestic battery industry and creating a footing for Indian manufacturers in the global energy storage market. India launched the National Programme on Advanced Chemistry Cell Battery Storage with an outlay of $2.5 billion over five years, which can enable large-scale domestic battery manufacturing and serve the dual purpose of boosting renewable electricity generation and transport electrification.

There has also been significant subnational action, as nearly 20 states have recently finalized or notified EV policies. India will still need a cumulative investment of more than $180 billion this decade to meet 2030 goals and a stronger policy framework to resolve challenges related to upfront EV cost, battery sustainability, and infrastructure development. A concerted policy push will be key to bolstering a competitive EV ecosystem and capitalizing on benefits from targeting new frontiers like heavy-duty vehicles.

The road to 2030

As India looks ahead at the next 75 years, it can chart a development pathway that avoids locking in emissions-intensive infrastructure. This will require significant domestic and global resources and willpower. Key factors will include timely and adequate policy interventions, private sector led-innovation, and the rapid availability of low-cost capital. Drastic drops in the cost of solar and government schemes like KUSUM and Saubhagya, for example, have led to affordable and sustainable energy solutions for rural communities across the agrarian value chain.

The real challenge for India, however, lies in simultaneously bringing millions of people out of poverty. The impact of climate change in the country is also being felt more acutely in heat waves and other extreme weather phenomena. India’s prime objective has been to ensure its decarbonization journey is in step with achieving sustainable development goals.

Compared with other industrialized countries, India’s pace of deploying clean, affordable, and efficient energy systems will have to be much faster as it also seeks to guarantee access to energy and mobility, clean cooking fuel, food security, cooling, and disaster resilience.

What lies ahead is the difficult but imperative task of providing sustainable livelihoods, clean air, and a just and equitable transition to clean energy. Can India replicate, scale, and capitalize on its successes to showcase inclusive, low-carbon economic growth for developing countries? India is demonstrating leadership and emerging as a clean energy solutions provider. But the international community has a vital role to play in catalyzing this momentum and enabling India’s successful transition. The years leading up to 2030 will be crucial.

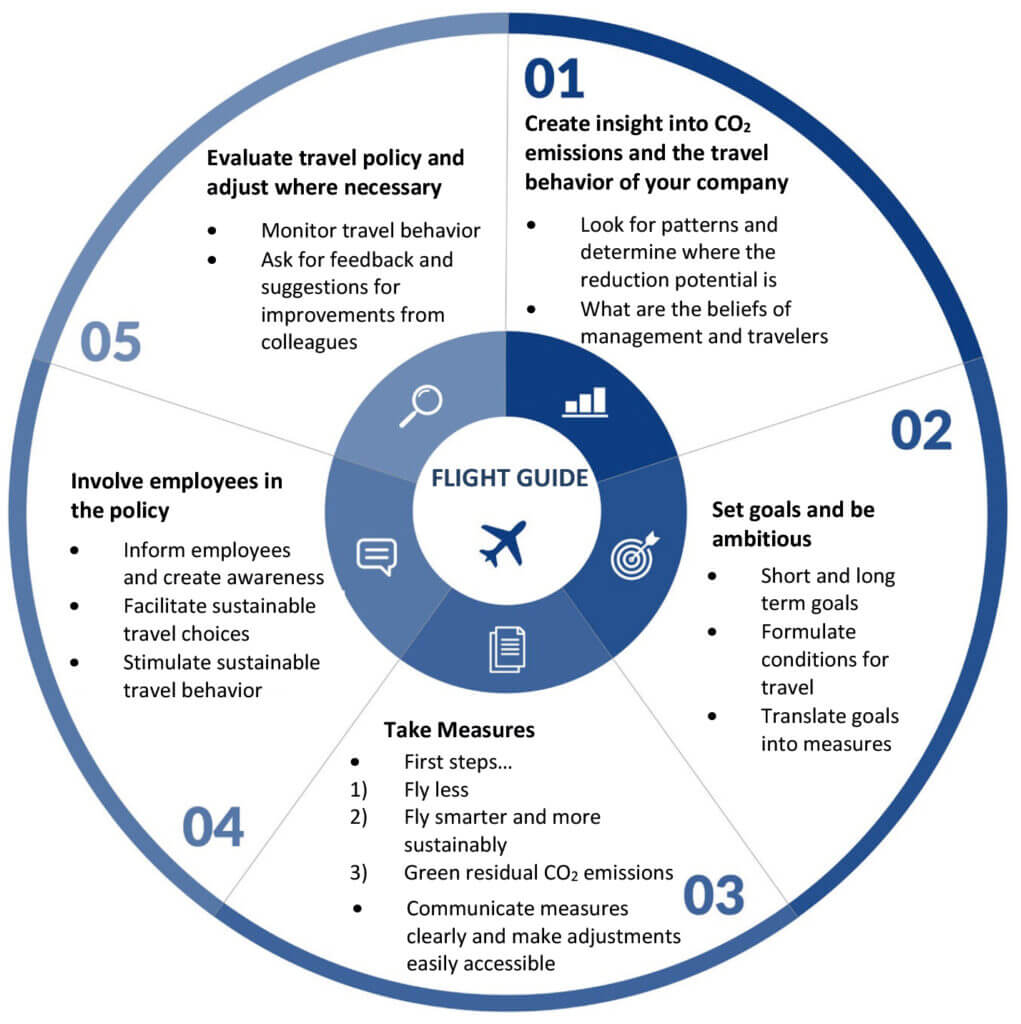

Before the pandemic brought global travel to an abrupt halt in early 2020, extensive government and business travel for workshops, meetings, and seminars was the norm. In-person attendance was considered polite and good for business and, in turn, propped up decades of increasing demand for corporate flights. Covid-19 challenged this standard and proved that much of the demand for business travel is artificially induced and, more often than not, simply unnecessary.

This shift in behavior revealed two insights. First, corporations can save on operational costs for business flights while championing a reduction of aviation emissions. Second, demand reduction is a viable pillar to decarbonizing the aviation sector alongside strategies to advance sustainable aviation fuels and zero-emission aircraft.

Aviation growth is undeniable

Emissions from global travel are projected to grow from an estimated 2% of global carbon emissions today to 12-27% of emissions by 2050. According to the UN’s aviation agency, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), global passenger traffic will grow 3.6% annually through 2050. As we discussed in a previous blog post, aviation’s effects on the climate are not limited to CO2 emissions. The negative effects of emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx), soot particles, oxidized sulfur, and water vapor high in the atmosphere are estimated at two times those of CO2. While the aviation sector is starting to make strides toward expanding the base of sustainable aviation fuels and exploring other technologies for zero-emission flights. In the meantime, demand reduction through smart business engagement represents a key near-term solution to reducing aviation emissions.

Why business travel matters for aviation decarbonization

Only 1% of the global population is responsible for 50% of emissions from flying, and a big share of this — about 30% in Europe — comes from corporate flyers, often with high-polluting business class long-haul flights. Moreover, business travelers make up some 12% of passengers but up to 75% of revenues on certain flights, so their choices have important leverage on the aviation industry. Given their significant purchasing power, companies are in a unique position to influence the acceleration of sustainable aviation and to reduce their travel emissions by reducing their business travel. The pandemic has provided an unprecedented opportunity to lock in reductions in global corporate flying and to introduce a new culture of purposeful and effective travel.

For many companies, business air travel is a large part of their CO2 footprint, including up to 60-80% for service provider companies (e.g. consultancy and finance). As part of their new Travel Smart Campaign, ClimateWorks Foundation partner Transport & Environment recently published a ranking of 230 global companies as a way to drive business accountability and transparency. The ranking reveals that 80% of the companies fail to act with sufficient speed and ambition to tackle corporate travel emissions.

But the benchmark also highlights that some companies are leading the way, championing the ranking, and demonstrating that it is not only possible but beneficial for companies to address business travel emissions. “Traveling smart” means saving money for businesses and meeting evolving investor expectations to cut costs, while also protecting employees’ well-being and showing leadership in the climate crisis. This global campaign asks businesses to learn from climate breakthroughs made by others and join forces to accelerate the decarbonization of aviation. It challenges companies to reduce air corporate travel emissions by 50% or more from 2019 levels by 2025.

Corporate action as a lever for sustainable aviation

Global corporations drive lucrative business air travel and as such, their behavior can set a strong precedent for the aviation market. As more corporations publicly announce targets for reducing business travel emissions, philanthropy must take advantage of this moment by supporting campaigns that target accountability, increase ambition, and push for immediate action. Reducing demand for business travel is an obvious win for decarbonizing the aviation sector that cuts costs for businesses and achieves immediate emissions reductions. It is also a solution that allows corporations to act now on reducing emissions, rather than wait for future technological advances, like sustainable aviation fuels. Visit the Travel Smart Campaign website, to learn more about immediate steps that can be taken to reduce business travel demand.

Apollonia “Apple” Cuneo joined the Industry Program at ClimateWorks for a summer internship in 2022 through the Empowering Diverse Climate Talent (EDICT) program. Here she shares reflections and learnings on the importance and promise of low-carbon building materials.

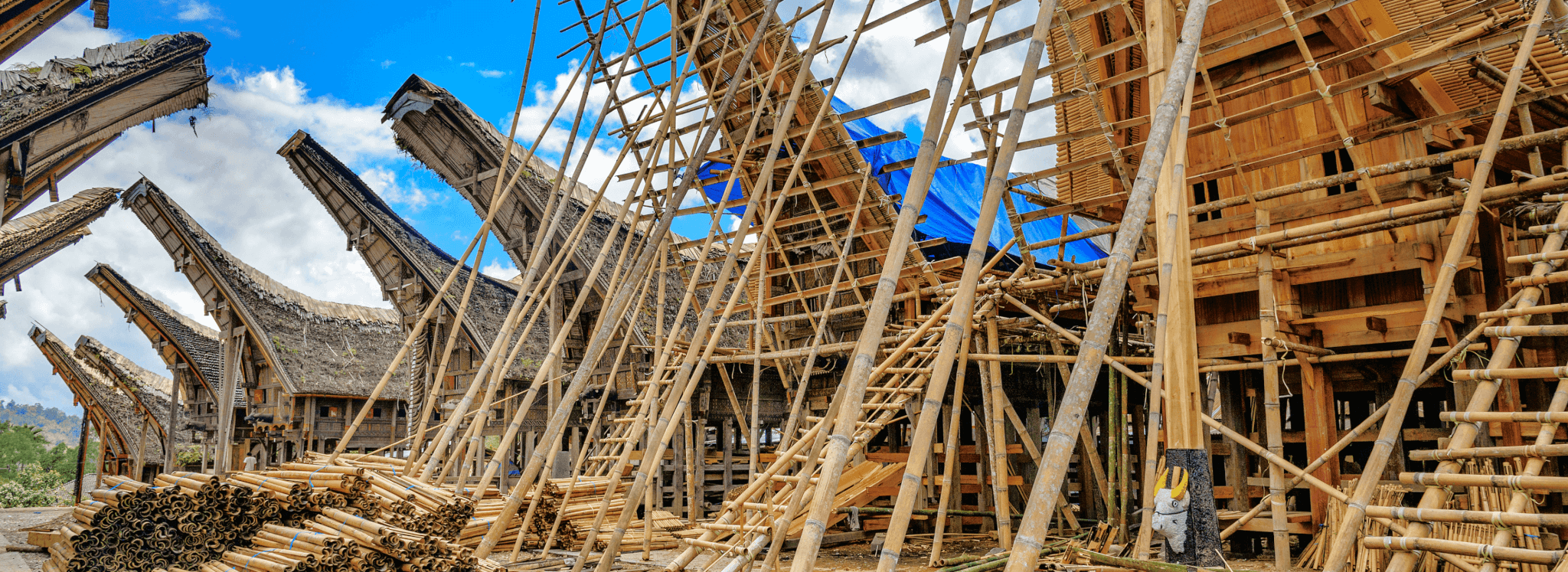

After decades of policy initiatives to make buildings more energy efficient, the embodied carbon of building materials is finally gaining more attention. Recent policy initiatives ranging from the Buy Clean California Act to President Biden’s Buy Clean Task Force could transform the production of the most carbon-intensive building materials like steel and cement, leading to dramatic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. However, efforts to decarbonize building materials should expand to include alternative building materials like bamboo, wood, and straw. Philanthropy can play a key role in realizing the potential of these biogenic materials to decarbonize the built environment.

Building Materials

If you are reading this blog post at home, work, or school, you are probably sitting in a building made largely of cement, steel, and aluminum. These materials make up the foundation and structure for most contemporary buildings, but the production of these construction materials accounts for about 8% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. Changes in production processes and greater material efficiency are key to decarbonizing the industrial sector, but these are not the only options to reduce embodied emissions.

For millennia, people used earthen materials to build homes, businesses, and places of worship. In fact, some natural building techniques have been passed on for generations and are still used worldwide. From Portugal’s Paderne Castle to the Old Walled City of Shibam, many structures made from local materials like soil and stones have stood the test of time. These monuments to human ingenuity remind us that we can make durable, functional buildings from natural materials without warming the planet.

Efforts to decarbonize building materials should expand to include alternative building materials like bamboo, wood, and straw. Philanthropy can play a key role in realizing the potential of these biogenic materials to decarbonize the built environment.

Wood, bamboo, and straw are not novel building materials, but they are receiving renewed attention in light of recent efforts to reduce the embodied emissions of industrial products. Wood products like cross-laminated timber have an excellent strength-to-weight ratio and are widely available. Bamboo grows quickly, is relatively inexpensive, and is very sturdy. Straw is typically a byproduct of agricultural grain products like wheat and can be used for insulation. Bamboo and straw can be combined with wood to construct load-bearing walls with relatively little embodied carbon, as demonstrated by the manufacturers EcoCocon and BamCore. For example, BamCore’s biogenic walls contribute to reductions of 125 metric tons of CO2 for an average two-story home over a 70-year service life in the United States.

Biogenic materials have additional benefits. They embrace the liminal space between the indoors and outdoors, improving our mental well-being and enhancing our connection to the environment. If locally sourced, biogenic materials can foster job growth and support local economies, thereby strengthening our communities. Furthermore, when structures are designed for disassembly, biogenic materials are easily recycled and reused.

To complement other efforts that move us away from a fossil fuel-based economy, the U.S. Department of Energy committed $39 million in June 2022 for research on biogenic materials in recognition of their potential to decarbonize the industrial sector.

The Challenges of Biogenic Materials

Although wood, bamboo, and straw have positive implications for our climate and health, there are two key obstacles to their large-scale development.

First, biogenic materials must be sustainable and equitable for all species to meet the UN sustainable development goals 8, 11 and 15. The destruction of forests to satisfy a growing demand for construction materials can undermine any climate benefits of building with wood and cause significant biodiversity loss. Expanding planted wood production in Europe and Turkey, for example, is correlated with species diversity loss. Many biogenic materials require adhesives to enhance their strength and scalability, but such binders must be derived from natural materials rather than fossil fuels. The production and use of biogenic materials must be thoughtfully designed, carefully executed, and well regulated, which will help avoid risks and promote long-term environmental benefits.

Second, biogenic materials must advance social justice instead of further marginalizing frontline communities. This means that the customary land rights and resource access of Indigenous communities should be respected. Sites where building materials are grown and harvested should not consume scarce resources in ways that lead to the displacement of people or food and water insecurity. The production of biogenic materials may reinforce historical inequities if the needs of local populations are subsumed by the economic imperatives of the construction industry. For example in Southern Chile, the forest industry’s recent growth has been associated not with a reduction in unemployment or an increase in salary, but with increased poverty amongst the local populations. Local communities should be involved at all stages of production and share the benefits of biogenic buildings, with residents defining the benefits.

Philanthropy’s Role

Philanthropy can help maximize the potential of biogenic building materials and minimize their drawbacks. Specifically, funders can do the following:

- Fund research on the most promising materials, the most sustainable production pathways, and the most significant environmental justice issues.

- Support advocacy for policy initiatives that scale up research and development on biogenic materials, launch pilot projects, and establish regulations to guide production and use.

- Encourage the use of biogenic materials in historically marginalized communities, including in the Global South.

- Convene biogenic material producers, architects, engineers, contractors, and other stakeholders to strategize about scaling up production and use in climate-compatible ways that also meet environmental justice goals.

Reducing the embodied carbon in building materials requires a holistic approach that includes both creating demand for low-emissions industrial materials and scaling up the use of biogenic building components. By pairing these approaches, we can build more without baking the planet.

Electric transportation of all kinds helps mitigate climate change, reduce air pollution, and improve health outcomes — and offers a key opportunity to help end global dependency on oil. However, until a truly circular design is viable, producing any vehicle relies on materials such as steel, oil, and a number of minerals. Electric vehicles already drastically reduce the volume of raw materials needed to power our transportation system. Still, there is a growing recognition that getting to 100% electrified transportation will require an expanded supply of critical minerals.

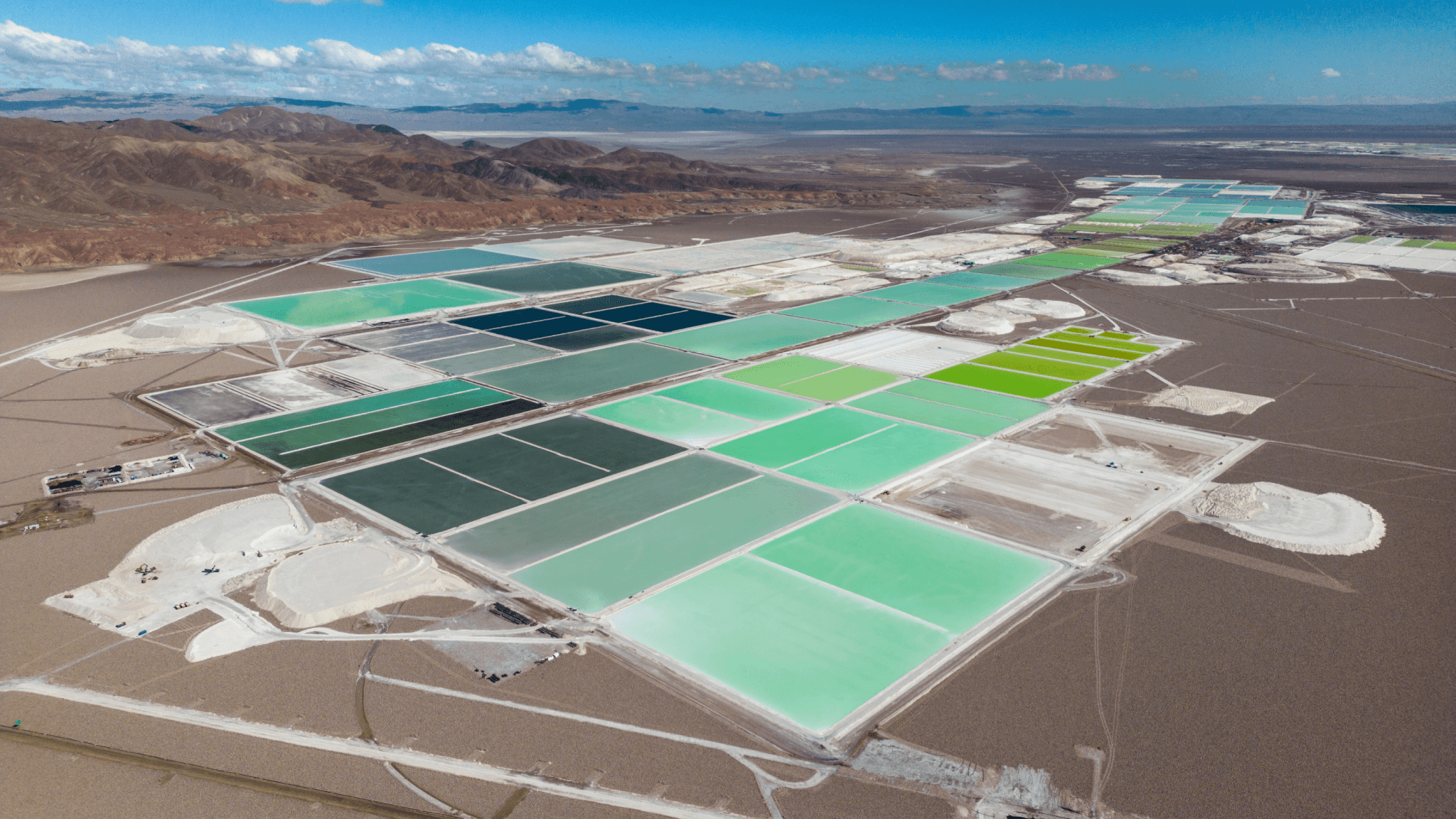

Recycling can provide between 25% and 55% of the expected growth in minerals needed for electric vehicle batteries, and additional minerals must be extracted with the lowest possible impact on communities and the environment. In our previous blog post, we shed light on the impacts of mining for critical minerals and the priorities for policies to improve the battery supply chain. Currently, the European Union, China, India, and the United States are taking steps to review their domestic slice of the global battery supply chain and draft responsive regulations that address mining for critical minerals, battery manufacturing, and its end-of-life practices.

One voluntary standard is emerging as an important tool in service of both industry and policy ambitions for improving mining impacts. The Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) provides a template for model regulations on mining practices and is making strides to support automakers and battery manufacturers in leveraging their growing demand for minerals to incentivize necessary change in mining.

A singular mining standard that considers responsibility from multiple perspectives

The IRMA Standard for Responsible Mining is a one-of-a-kind standard that measures global mine sites against a set of best practices developed over a decade through multi-stakeholder dialogue. IRMA is the only standard for large-scale mining that is governed equally by NGOs, labor unions, mining-affected communities working alongside mining companies, the finance sector, and companies who purchase mined materials for the products they make (e.g. vehicles, jewelry, electronics, wind turbines, etc.). It offers both expertise and a pathway for transforming the mining sector. As a voluntary initiative, it will never replace the essential need for laws and regulations that would bind all companies. But governments and citizen advocates can use IRMA’s 15 years of work to help define best practices for protecting human rights, clean water, biodiversity, Indigenous rights, worker rights, and economic opportunities after a mine closes.

More than a decade of work went into developing the standard, including global public comment periods for the first draft in 2014 and the second draft in 2016. Cross-stakeholder working groups weighed in on controversial issues, and the draft standard underwent field tests at mines in the United States and Zimbabwe. The final standard integrated all that feedback and is now available for auditing, with 26 chapters built around four main principles: social responsibility, environmental responsibility, business integrity, and planning for positive legacies.

As a tool for creating positive market pressure, IRMA offers an opportunity for automakers and component manufacturers to use the IRMA Standard and audits of mines as a tool in their due diligence to understand harm in the supply chain and to leverage improved practices. Already, consumer-facing brands are developing new purchasing contracts that ask suppliers to be audited against the IRMA Standard, share detailed information on performance, show improvement, and reach key achievement levels in a time-bound schedule. For example, in the automotive sector, BMW, Mercedes, Ford Motor, GM, Volkswagen, and Tesla have all joined IRMA.

IRMA is a key stakeholder in helping governments develop a regulatory pathway for improved mining practices. The initiative has been uniquely referenced in the Biden Administration’s report on sustainable supply chains, in critical minerals strategy by the European Parliament, and in a report supported by the Australian government evaluating which standards would make Australian materials most competitive in the European markets for battery materials. The latter identifies IRMA as a “no regrets approach” because of the comprehensive nature of the standard and IRMA’s multi-stakeholder base.

The IRMA standard makes it a key benchmark for indicators across a wide range of advocacy spaces. As we move to energy sources that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we must not exacerbate the impacts already in progress in a climate-stressed world. By connecting voices from different aspects of mining, IRMA’s coverage of diverse issues helps to ensure that we do not trade issues off one another. By measuring the impacts of mining operations against the full range of issues, we can have a fuller picture to support solutions that more holistically address a world responding to drought, flooding, and increased conflict.

Empowering philanthropic engagement

Philanthropic support for electrification can go hand-in-hand with supporting the field in advancing the sustainability of batteries. While we push to end tailpipe pollution that harms the climate and burdens communities, we can support the growing call to embed improved mineral sourcing practices, circularity, and even net-zero manufacturing into our vision of a clean transportation future. The global nature of the battery supply chain and the broad application of minerals that power the climate transition offers philanthropy an opportunity to deepen engagement.

We can amplify our impact at the ground level of the battery supply chain with a consistent and unified voice. For example, philanthropic partners and grantees alike can spotlight the IRMA Standard as a vector for corporate engagement and a template for government regulations. We need to signal externally that it is possible for automakers and battery manufacturers to be a force for improvement. Preventing greenwashing is also critical, which is why we need comprehensive best-practice standards that are accountable to NGOs, labor unions, Indigenous communities, and others directly impacted by mining. In turn, we can continue to build advocacy power toward binding regulations on mineral sourcing, battery recycling, and end-of-life practices.

Because this work touches so many lives and key issues, this is an opportunity for philanthropic collaboration across expertise and dedication to human rights, clean water, biodiversity and conservation, Indigenous stewardship, worker rights, heavy industry, climate mitigation, and more. In our next blog post, we will dive deeper into organizational approaches for working on transitional minerals and share our learning from working with philanthropic partners.

Electric, climate-friendly TRUs can ensure the delivery of life-saving goods, support frontline communities along trucking routes, and limit emissions.

The heatwave in Europe is the latest in a year of devastating extreme weather around the globe, from wildfires to power shortages and record-breaking temperatures. Extreme heat events make us all acutely aware of the importance of access to cooling, like the mighty refrigerator.

While refrigerators do keep our food fresh, they also go beyond the home to store and transport vaccines, medicine, and donated blood or tissue – they are truly lifesaving. Transport Refrigeration Units (TRU) are refrigeration systems that provide temperature control for transportable perishable products. You might see them at a grocery store where workers are delivering fresh vegetables, or at a hospital where staff unload medicine, or even circling the neighborhood with ice cream on a hot day.

When trucks and railcars congregate along corridors or idle near logistics hubs, they pose significant health risks to people who work and live nearby, often low-income communities.

Yet the refrigerants used in today’s refrigerators are super-pollutants that typically leak into the atmosphere and can be thousands of times more potent than carbon dioxide. Further, the majority of the mobile refrigeration units used today run on dirty diesel fuel. Currently, TRUs are mounted on various containers, including trucks, semi-truck trailers, shipping containers, and railcars.

These dirty diesel engines power the truck and its cooling system, emitting particulate pollution that causes asthma and increases cancer risk. Although some of these units are relatively small, when trucks and railcars congregate along corridors or idle near logistics hubs, they pose significant health risks to people who work and live nearby, often low-income communities. More than 56,000 TRUs are operating every day in California, so the Air Resources Board modeled the health impacts for communities in the Central Valley where cold storage is an essential part of the agricultural industry. Based on local conditions, a TRU running 8,000 hours per week causes a potential cancer risk for nearly 1,800 people per million living close to cold-storage warehouses, and 600 people per million living near grocery stores.

And rising global temperatures are driving increased demand for cooling, which contributes to the climate crisis and ultimately creates the need for even more cooling. This has created a vicious feedback loop where the technology that keeps things cool, makes our world warmer. While these mobile cooling systems in their conventional form are highly polluting, more environmentally-friendly alternatives exist. However, with any new technological disruption, an incumbent and entrenched industry is slow to shift to zero-emission options.

Rising global temperatures are driving increased demand for cooling, which contributes to the climate crisis and ultimately creates the need for even more cooling.

In response to both the climate threat and impact on frontline communities, the California Air Resources Board voted earlier this year to phase out all diesel-powered TRUs in favor of zero-emission models by 2030, and to require the use of refrigerants that have lower global warming potential (GWP, a cooling industry metric). The policy includes a mix of incentives and regulations, driven by community input to clean up trucking. This approach is a good start and could be further strengthened and replicated in other places in the U.S. and internationally. Climate philanthropy has been effectively investing in community coalitions, policy frameworks, and industry leadership to advance clean trucks and curb emissions from the cooling sector, including the cold chain.

It’s important that we don’t sideline these specialized trucks as more of the world looks to bring TRUs into supply chains and onto local roads. Each year, a lack of adequate refrigeration leads to global food loss of 13%, which contributes to rising greenhouse gas emissions and rates of hunger. To mitigate these global and overlapping impacts, we need to better understand the scope of the problem and solutions that will drive accessible alternatives, aligned with our climate and equity goals. This is one example of where we can collaborate across sectors – drawing on expertise and a strong partner network in our Road Transportation and Clean Cooling programs. Through this crossover lens, we can highlight how electric, climate-friendly TRUs can ensure the delivery of life-saving goods, support frontline communities along trucking routes, and limit emissions.

With less than a decade to cut in half global emissions, the world needs to move faster, and philanthropy must challenge itself to do more. With the climate clock ticking, slowly winning is akin to losing.

Climate change alarm bells have been ringing for decades, but only more recently has the crisis begun to unfold at a breathtaking pace with far-reaching impacts that leave no community untouched. As the climate emergency has intensified, the philanthropic response has shifted from whether to act to how quickly and at what scale we must act.

Philanthropy has often stood at the vanguard of drawing attention to wicked problems and mobilizing resources to create needed change. Climate change is one such wicked problem to which philanthropy has been steadily increasing its attention over the last 15 years.

While global philanthropic giving dedicated to climate change mitigation remains at less than two percent of total philanthropic giving, there are positive indicators of growth in giving to climate. From 2019 to 2020, there was a 14 percent increase in giving to climate, including more giving from major donors, new funders, and collaborative commitments — and this trend is likely to continue and accelerate. But with less than a decade to cut in half global emissions, the world needs to move faster, and philanthropy must challenge itself to do more. With the climate clock ticking, slowly winning is akin to losing.

New report sheds light on the growth of climate curious

The latest report from the Center of Effective Philanthropy (CEP), Much Alarm, Limited Action: Foundations & Climate Change, outlines how the ranks of the climate curious have grown among foundation and nonprofit leaders alike. Over 90 percent of foundations and nonprofit leaders said climate change was an urgent problem. And more than 70 percent said climate change will negatively affect the issues their foundation focuses on and their foundation’s ability to achieve its goals. But despite agreement that public and private sectors should do more to address climate change and that philanthropy can engage more deeply and effectively to combat climate change, leaders described foundation efforts as relatively limited in terms of grant dollars and investment practices.

While there is widespread recognition of the threats posed by climate change, less is understood by many funders about the “what” and “how” of engaging on the issue. The good news for philanthropic and nonprofit leaders is that there are myriad opportunities to explore intersectional approaches that leverage the power of collective action to benefit their work, tackle the climate crisis, and improve people’s lives in communities around the world.

Philanthropy in action: Intersectional approaches, bold action

Whether a funder is geographically- or issue-focused, great examples highlight the power of working collectively to take intersectional approaches and advance bold action. Barr Foundation in New England stands out for its community investments to shift to clean energy, prioritize equity, and create climate resilient communities in its work across arts, climate, and education. Also, the George Gund Foundation’s efforts to strengthen community in Cleveland has led them to tackle interrelated issues through a local lens, including climate change and environmental degradation, inequality, and weakened democracy.

Or take an issue that touches most: transportation. Transport emissions impact air quality and health. But considering it only through the lens of transport didn’t yield the funding needed to bring transformation necessary to benefit the climate, public health, and the economy. A new approach with the Drive Electric Campaign exemplifies the rapid progress possible when the collective power of diverse groups is tapped.

Drive Electric is powered by more than 80 organizations and a global strategy that leverages smart government policies, business leadership and action, and people power, including diverse organizations and coalitions representing the environment, local communities, health, labor, consumers, business, and equity. Launched in 2020 and working in over 65 countries, Drive Electric partners have already made incredible progress. Today, 24 percent of world transportation is committed to transitioning to 100 percent zero-emission by or before 2050. By accelerating electrification, Drive Electric will help avoid over 160 billion tons of cumulative carbon pollution over the next 40 years, avert trillions of dollars in climate damages, save lives, create jobs, and improve the economy.

Cooling is another intersectional area where funders and partners with varying priorities across energy access, climate mitigation, and climate adaptation have come together through the Clean Cooling Collaborative to collectively advance the climate and development benefits of efficient, climate-friendly cooling for all. Since 2017, the Clean Cooling Collaborative has mobilized the investment of over $600 million in public and private finance for efficient, climate-friendly cooling, advanced cooling programs and policies in 57 countries, and secured over 2.4 gigatons of avoided CO2 emissions by 2050.

Resources to learn and act on climate

Perhaps the most promising data point uncovered in CEP’s report is that 45 percent of foundation and nonprofit leaders have not closed the door on the possibility of funding climate change. This reinforces that there is a large number of folks within philanthropy that are open to joining the climate fight but may not know where to start.

With the growing and diversifying ecosystem of expertise across regions, sectors, and people-centered strategies, there is help funders can turn to. These organizations have resources to support philanthropic funders new to climate and connect them to high-impact solutions related to their respective organizational priorities: the African Climate Foundation, the Clean Air Fund, the Climate Leadership Initiative (CLI), Energy Foundation, the Hive Fund for Climate and Gender Justice, and The Solutions Project, just to name a few. My organization, ClimateWorks Foundation, is also a resource for funders looking for climate insights, investment-ready programmatic strategies, and collaboration opportunities with fellow funders.

The climate crisis is the defining issue of our time, and the window to avoid the worst outcomes is rapidly narrowing. CEP’s report is an important contribution to broader dialogues on the widespread implications of climate change and the role philanthropy can play to ramp up momentum. By moving more resources into multi-solutions faster and driving radical collaborations across the broad philanthropic landscape, funders can address issues near and dear to them AND tackle climate change. There is room for everyone in philanthropy to lend a helping hand, and it’s never been easier to jump in. Welcome!

This post was originally published on the Center for Effective Philanthropy’s blog here.

We all know by now that we are warming the planet at an alarming rate due to our runaway greenhouse gas emissions, and that we’re going to have to decarbonize very rapidly and arrive at net-zero emissions by mid-century in order to have a fighting chance to keep global temperature rise to below 1.5C.

We also know that this is achievable, but it will take strong and unwavering policy action from governments, greater international cooperation, effort from all of us—and money. A lot of money: McKinsey estimates that more than $9 trillion per year on average will need to be spent between now and 2050 on physical assets for energy and land use systems. Not all of this is “new” spending, but even so, we will need to invest $3.5 trillion per year more than we currently do while reorienting some of our current spending away from carbon-intensive activity.

And just as we will all need to work together to decarbonize, we will need to bring all sources of capital to bear to pay for all this.

The bulk of the investment will have to come from the private sector. Companies will need to invest to concretize their net-zero commitments. They will need to raise debt and equity from capital markets, so financial institutions will play a critical role. In addition to setting the right policies, the public sector will need to invest, either directly in state-owned assets, or indirectly, through (fiscal) support for private investment. Multilateral institutions—development banks as well as climate finance facilities like the Green Climate Fund—will need to step up and help countries make some of these investments. And developed nations will need to make good on their commitments to financially help developing countries achieve climate goals.

In addition to these usual suspects, another player needs to step up its contribution to the cause: philanthropy. A survey of foundations suggests that they provide $150 billion per year in philanthropic grants across a range of sectors and countries. This may be small in light of needs, but it is of the same order of magnitude as annual foreign aid (or overseas development assistance), and if used judiciously, these funds could help mobilize several multiples in investment flows.

“Blended” finance is a term that is much used these days. Essentially, it means using catalytic capital from public or private sources to crowd in private sector investment. Below are some examples of blended structures from my recent work. There are many more. They have been shown to work and they need to be scaled up.

Energy efficiency is a necessary component of our decarbonized future. But energy efficiency investments remain notoriously difficult to finance, despite having very attractive payback periods and internal rates of return. These projects tend to be disparate and small in size, which greatly increases transaction costs. Banks in many countries tend to collateralize their lending; energy efficiency improvements do not lend themselves to being easily collateralized. Loan officers may not be comfortable assessing the credit risk of such projects, while businesses may not easily find the expertise needed for energy audits and other preparatory work. Technical assistance can help build capacity, both in identifying and in evaluating energy efficiency measures, and donor (or philanthropic) funding can help finance it.

Such capacity constraints exist in different climate arenas. Investors lament the dearth of a bankable pipeline of climate-friendly projects, and developers face high upfront development costs that are not easily financed. Dedicated technical assistance and project preparation facilities can play a critical role in creating these bankable projects.

Concessional support—through multilateral, bilateral or mission investment channels—can play an important catalytic role in investment. These sources are prepared to accept lower returns, or take greater risk, than the market. The beauty of such support is that it can be tailored to the specific needs of the initiative, and can be structured in a way that crowds in private investment. One project might need a tranche of lower interest or longer tenor debt; another may need quasi-equity or mezzanine finance. Blended with more traditional sources of finance such as private equity or bank loans, concessional support can help create a capital structure to meet the different needs of the different investors. Such support is not available from commercial sources and could be the critical lynchpin in the deal.

Investors are reluctant to invest where the risks may not be well understood, or where perceptions of risk may be very high. Guarantee structures can help in risk mitigation—and climate finance or philanthropy can help, either by providing the guarantee, or covering first loss. Portfolio guarantees can increase the lending capacity of banks; credit enhancement can facilitate the raising of debt in capital markets: a stronger balance sheet, backed up by government commitments if needed, can provide the comfort necessary for investors to invest.

Where does philanthropy fit into all this? Philanthropic capital is employed across the entire returns spectrum, from grants to concessional investments to market rate investments. This means that there are multiple points of entry in terms of the support that philanthropy can bring to an endeavor. Grant funding can help with project preparation and technical assistance. Mission investment can provide concessional debt and equity, as well as guarantees or credit enhancement. And, as philanthropic foundations (and others) increasingly align their endowment investment with their values, there will be potentially large demand for climate-related assets – and an opportunity for financial institutions to get creative and provide the investment instruments that can attract such funding.

Global capital markets saw over $40 trillion in new issuance in fixed income securities and equities in 2020. Let’s channel some of this to investment in our long-term prosperity – let’s make a deal!

This post was originally published on the World Bank Group’s blog here.