Researchers are developing promising solutions to concrete’s high greenhouse gas emissions — one is ready to scale.

Concrete — a mixture of cement, sand, and gravel — is an essential and affordable material for buildings and infrastructure around the world. Globally, 4.2 billion tons of concrete are produced annually, and demand is expected to increase by 48% by 2050. Concrete is also responsible for 8% of global carbon emissions, making it a major driver of climate change. Simultaneously, however, a warming planet increases the need for concrete to create safe, resilient homes and infrastructure. Concrete is not going anywhere soon — which makes improving its sustainability all the more urgent.

To understand the potential opportunities for emissions reductions, it is helpful first to consider how cement is produced. The process starts with quarrying limestone rocks, sand, and clay, which are blended into a fine powder. Next, the powder is heated to high temperatures in a kiln to calcify limestone into lime, producing clinker. (This chemical process emits a large amount of carbon dioxide.) The clinker is mixed with gypsum and ground into a powder to create cement. The cement is then added to sand and gravel and mixed with water to produce concrete.

The process of producing clinker in cement is responsible for 90% of carbon emissions from concrete. Effective emissions reductions for concrete are possible by either reducing the clinker content in cement or changing the material content within the clinker.

Researchers worldwide have been working hard to reduce emissions by creating material and design efficiencies in planning for new infrastructure, decarbonizing electricity, and enhancing efficiency in cement production. Here are three key emerging technologies that could help solve the emissions challenges associated with concrete.

Going low-carbon: Limestone calcined clay cement (LC3)

Year invented: 2005

Country invented: Switzerland

Potential CO2 reductions: Concrete emissions reduction by 40% and savings of around 500 million tons of CO2 annually by 2030

The potential of the technology: Projected to account for more than one-quarter of cement used globally by 2050

In 2004, Karen Scrivener, the leading chemist on cement decarbonization and a professor at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, and Fernando Martirena, a professor at Universidad Central de las Villas (UCLV) in Cuba, first discussed the use of calcined clays as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) in cement. SCMs are materials added to concrete to enhance cement’s properties, lower its environmental impact, and reduce cement’s clinker content. In 2014, EPFL headed the first three-year phase of the LC3 project with support from UCLV and IIT Delhi. Since then, a growing number of projects have used limestone calcined clay to reduce the amount of clinker in cement.

Limestone calcined clay (LC3) is a mixture of clinker, calcined clays, limestone, and gypsum. Because of savings in energy and materials, LC3 is up to 25% more cost-effective than portland cement, the typical cement used everywhere. Research done by EPFL found that clay reserves are available and abundant worldwide. Unlike many proposed solutions, calcined clays can use existing equipment, offer adequate mechanical qualities, and are globally scalable..

The Cementos Argos plant in Rioclaro, Colombia, is the first large-scale calcined clay production facility and began operations in 2020. The clay is mined 10 miles away and processed in a newly built kiln. This new process has allowed a 30% cut in energy consumption and reduced the facility’s carbon output by half. The switch to LC3 did not slow cement production, as the facility can produce 1.4 megatons of LC3 a year.

In 2022, CBI Ghana signed an $80-million contract to construct the world’s largest calcined clay cement plant, which will substitute 30% to 40% of clinker and reduce carbon emissions from concrete by 40%. Moreover, the use of LC3 blocks will decrease the use of firebricks which are high in embodied carbon.

Even though LC3 is a cost-effective and energy-efficient substitute for traditional portland cement, some scalability barriers need to be overcome. Portland cement is a well-established technology that has been used for generations and is widely produced. Some cement companies are less open to changing how they produce cement and do not want to release capital to invest in new technologies to retrofit their factories. Scaling LC3 cement requires incentives and policies that help promote low-carbon cement production. In some jurisdictions, the use of LC3 cement may require updated standards and codes. Clay can be calcined in standard kilns, but some modifications are required in existing plants.

Nonetheless, there are significant opportunities for progress. Cement production is quickly growing in emerging economies, necessitating new cement plants that can be readily designed to make LC3 from the start. To better take advantage of LC3’s low-carbon benefits, it is essential to start building a market.

Bio-cement: Algae-grown limestone

Year invented: 2020

Country invented: United States

Potential CO2 reductions: Save 2 gigatons of CO2 and pull 250 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere

The potential of the technology: Estimated to grow between 25 and 50 tons of limestone per acre

In 2017, Wil Srubar, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, came up with the idea to explore how to grow limestone particles using microalgae during a snorkeling trip in Thailand. Srubar’s team has found that replacing limestone with algae-grown limestone out of coccolithophores — microalgae that sequester and store carbon dioxide in mineral form through photosynthesis — creates a net carbon-neutral and carbon-negative way to produce portland cement.

Coccolithophores are incredibly resilient and can live in salt water or fresh water and at high or low temperatures. The researchers see biogenic cement as a plug-and-play material that can be used in the traditional cement process.

The Colorado-based company Prometheus Materials utilizes algae to produce masonry blocks that achieved ASTM C129-22, Standard Specification for Nonloadbearing Concrete Masonry Units, and C90, Standard Specification for Loadbearing Concrete Masonry Units performance requirements. The blocks are also lighter, have a compressive strength that rivals traditional concrete, and reduce thermal transmission.

While algae-grown limestone has been demonstrated at a small scale, there are barriers. The primary issue with biogenic cement involves scaling it up affordably and then demonstrating its use in large-scale projects. The technology is also relatively new in its development and has a low Technical Readiness Level (TRL) and Adoption Readiness Level (ARL). This means that more evaluations are required before using the cement in the projects and scaling them to achieve significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Electric recycled cement

Year invented: 2022

Country invented: England

Potential CO2 reductions: 2 gigatons of CO2

The potential of the technology: Produce 1 billion tons annually by 2050

The inspiration for electric cement came to the University of Cambridge’s Dr. Cyrille Dunant during Covid-19 when he noticed that the chemistry of recycled cement was nearly identical to lime-flux used in steel recycling processes. Cambridge researchers believe the key to reducing clinker emissions is heating recycled cement in electric arc furnaces (EAFs). Concrete is crushed until cement separates from the aggregates and is then taken to an EAF to use in place of lime as a “flux” (a cleaning agent that removes impurities from molten metal). As the steel melts, the flux forms a slag that is similar to portland cement when cooled and ground up.

Researchers believe electric recycled cement will have the same durability as traditional cement due to its similar composition. The cement provides cost-savings because it uses existing steel production equipment that researchers believe can be scaled rapidly. The cement can also potentially be carbon neutral because emissions have already occurred through the original concrete production and if the EAFs are powered by renewable energy.

Celsa Group, a multinational group of steel companies, replicated this process at scale in its EAFs in Cardiff, known as the Cement 2 Zero project. The trials include 12 induction furnace trials and 8 trials in the Institute’s 7-ton EAF. The company and researchers hope the method will produce up to 30 tons of recycled cement per hour.

Some issues that have come up with this process are that the equipment needs reliable renewable energy inputs, and a supply chain needs to be developed. Two other crucial issues involve sourcing sufficient quantities of concrete waste and reaching the required temperature to produce the cement, which is much higher than the usual temperature in a cement kiln. The technology is also relatively new and has a low Technical Readiness Level and Adoption Readiness Level, meaning more evaluations must be done before using the cement in current projects and scaling to a degree where there is a significant impact on greenhouse gas reduction.

Notable startup companies working on low-carbon cement

These emerging methods and technologies are only some of the new ways researchers and industry experts are finding solutions to reduce concrete emissions — and more efforts are emerging. For example, companies like Sublime, Fortera, and Brimstone are using novel chemistries to change the chemical reaction used to create cement.

Sublime, based in Massachusetts, turns limestone into lime through an electrolytic process, which involves using an electric current to change a substance. Sublime’s technology can be fueled by renewable energy and the process allows for cement’s ingredients to be broken down at room temperature. A small quantity of the cement was used on One Boston Wharf, where it was mixed in a ready-mix concrete truck, maintained workability, and poured out of the concrete truck. Sublime plans to open a demonstration plant in early 2026 in Holyoke, Massachusetts, where it will produce 30,000 tons of clean cement per year.

Based in California, Fortera uses a technology that works within existing cement facilities. The technology takes the carbon released by the kilns and routes it back into the process to make additional cement by mixing the CO2 with calcium oxide to make ReAct Cement™. Fortera has opened its first demonstration plant in Redding, California, where it will capture 6,600 tons of CO2 and produce 15,000 tons of low-carbon ReAct Cement™. There will also be a 70% reduction of carbon emissions on a ton-for-ton basis, and the process will eliminate the feedstock waste associated with traditional concrete production.

Brimstone, based in California, uses calcium silicate rock instead of limestone to create a different chemical reaction without CO2 emissions. Instead of heating limestone to create lime, the company extracts calcium oxide from the rock — which does not release CO2. While these processes are different, the cement produced is chemically and physically identical to traditional cement. Brimstone’s first plant will produce up to a combined 140,000 metric tons per year of Ordinary Portland Cement and SCMs. The plant will also prevent 120,000 metric tons of CO2 emissions annually.

Brimstone and Sublime have recently been selected for award negotiations under the Department of Energy’s Industrial Demonstration Program and are starting to make waves in the construction industry. These grants will help these new companies scale up and build their first commercial-scale plants. Getting to scale is essential to reducing costs and making low-carbon cement commercially viable.

Reducing carbon emissions within the cement and concrete industry has become a top priority for researchers, innovative owners and developers, architects, engineers, and leading cement and concrete companies. While these emerging technologies are great steps forward, it is time to accelerate an effective transformation of the concrete industry. It is essential to collaborate across sectors and deploy a fuller range of strategies — including material and design efficiencies, decarbonizing electricity, and efficiency in cement and concrete production — to reduce emissions.

Tharika Lecamwasam is a 2024 summer intern for ClimateWorks’ Industry program, where she researched low-carbon cement technologies that can reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the concrete industry. She is currently a senior at the University of Massachusetts Amherst majoring in Sustainable Community Development with a concentration in the Built Environment. She minors in Information Technology and will receive a certificate in Integrated Concentration in STEM.

Direct air capture hubs can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere — and help advance a just transition toward greener jobs.

While reducing emissions is the most effective strategy to address climate change, the excess carbon dioxide that will remain in the atmosphere will need to be removed in parallel. Given that global emissions and temperatures have reached record highs, developing carbon dioxide removal (CDR) strategies now creates opportunities for removing vast amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, especially in the latter half of the century. CDR is critical for achieving the 1.5° C goals outlined in the Paris Agreement and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 — provided that it does not extend a license to continue fossil fuel use.

To date, philanthropic funding for CDR has focused mostly on nature-based solutions like preparing forests, soils, and oceans to absorb carbon dioxide. While these are low-cost removal approaches that can scale right away, they cannot do the job alone. In addition to requiring vast amounts of land, nature-based solutions are increasingly vulnerable to climate change impacts.

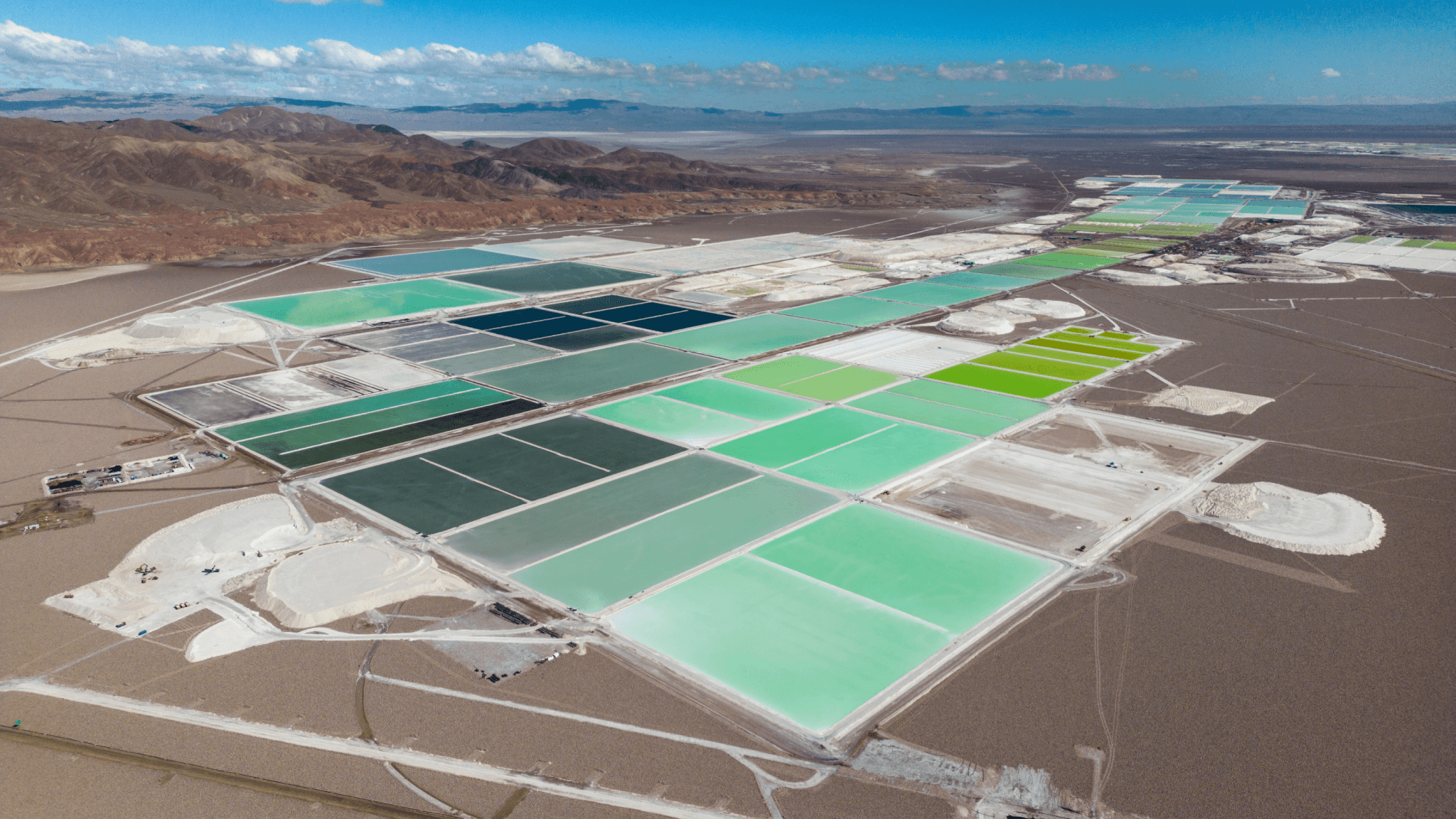

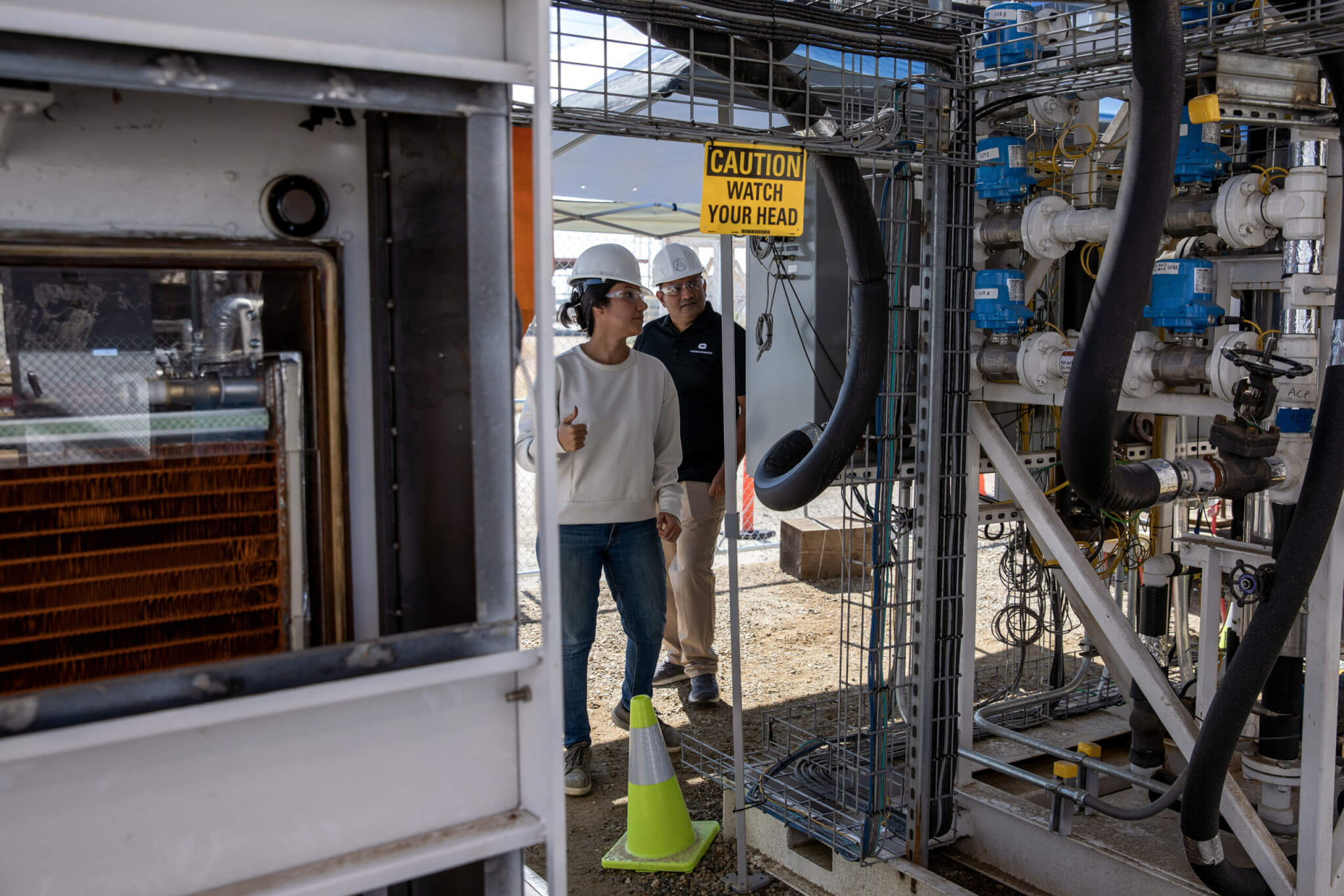

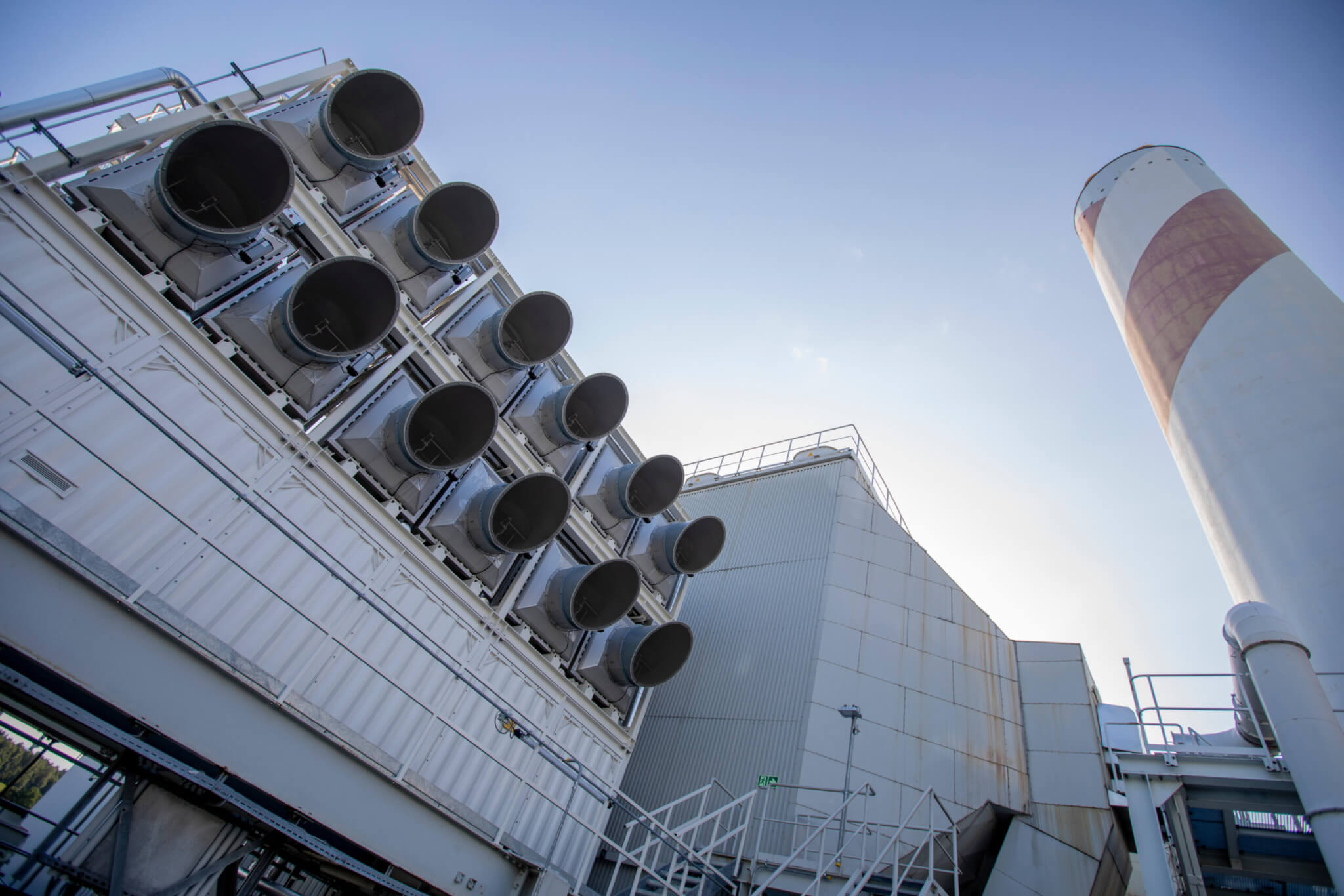

Technological approaches such as direct air capture (DAC) — which uses fans to extract excess carbon dioxide from the air and then fuses it to rocks underground — can offer potentially more long-term solutions to complement nature-based strategies, and can withstand threats such as deforestation, wildfires, and tilling. In contrast to carbon capture and storage, DAC removes carbon dioxide from the air rather than at the emission source. In other words, DAC targets the carbon dioxide that will remain in the atmosphere even after emission reductions. Community-driven strategies are critical for helping ensure that DAC and other CDR efforts support decarbonization, benefit communities, and avoid replicating historic injustices.

Increasingly, emerging technology companies recognize the importance of accelerating carbon removal solutions. “We owe it to every climate vulnerable citizen to continue to deploy our technology at the urgent pace required to reach billion-ton scale and beyond in time to stop the worst of climate change,” shared Shashank Samala, co-founder of Heirloom, a DAC-focused company.

DAC hubs: A model for strategic investment

To ensure solutions like DAC are ready to scale by 2050, investors are beginning to fund them now, taking lessons from successful efforts to scale solar technology. Thanks to decades of strategic funding from the public and philanthropic sectors, the price of solar photovoltaic electricity dropped 89% between 2010 and 2022, and solar was the world’s fastest-growing source of electricity in 2023 for the 19th year in a row. A major catalyst for solar breakthroughs in the United States was the Obama administration’s creation of regional innovation hubs, which prioritized funding and incentives for utility-scale solar projects and accelerated green energy generation.

In an attempt to achieve similar successes for CDR, the Biden administration announced in 2022 a $3.7 billion investment to boost the industry in the United States. This investment supports the creation of regional hubs of CDR facilities, or “DAC hubs.” These hubs bring workers, engineers, communities, and other decision-makers together to drive continuous carbon removal innovation — all while advancing health and economic prosperity and working toward climate change mitigation goals. The funding has already unlocked an abundance of DAC research and development projects, building on years of foundational work supported by the public, private, and philanthropic sectors.

How philanthropy is helping scale DAC

Philanthropy has helped lay the groundwork for the growing public and private interest in a wide range of CDR approaches, including DAC. In 2018, ClimateWorks Foundation established its CDR program — the first coordinated approach from philanthropy to engage with environmental justice groups, policymakers, and advocates in scaling up CDR methods. “Together with our partners, ClimateWorks has had the opportunity to help build the field of CDR philanthropy — and to work on the responsible scaling of carbon dioxide removal solutions,” said Jan Mazurek, senior director for aviation and carbon dioxide removal at ClimateWorks.

Philanthropy has supported efforts to help ensure the just and equitable implementation of DAC hubs without the involvement of the oil industry.

Funders and leaders across industries have come together to help emerging strategies like DAC develop in a way that benefits people, supports decarbonization, and reduces reliance on oil companies — the group that has invested the most thus far in scaling DAC.

Philanthropy also supports the dissemination of research to public audiences, which can foster dialogue and build support for regionally appropriate and equitable CDR. One such example is the 2024 Roads to Removal report. Published by 13 research institutions and 68 subject matter experts, the report highlights regional opportunities for removing atmospheric carbon while producing environmental and socioeconomic benefits like improved air quality and well-paying jobs. Analyses like the Roads to Removal report will help to build momentum and community support for people-centered CDR solutions.

While funding for carbon dioxide removal has grown steadily since 2015, it remains a small fraction of overall foundation funding for climate change mitigation — about 5% of all climate philanthropic funding. From 2016 to 2020, annual foundation funding for carbon dioxide removal averaged around $50 million per year, according to ClimateWorks data. In 2021, foundation funding jumped to $155 million, the second-fastest growing sector that year. Since 2018, the majority of CDR funding has supported ecological strategies like forest restoration, with only about 14% of cumulative CDR funding going to technological solutions such as DAC.

Here are three ways philanthropy has supported efforts to scale direct air capture.

Sparking public and private investment by funding exploratory research

Philanthropy-supported research has helped seed public ambition, influencing policy and unlocking public funds. This has included funding research about the cost efficiency, feasibility, economic benefits, and associated risks of DAC technology. Additionally, philanthropy supported the development of research about CDR investment opportunities that has since informed recovery act legislation, including the the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IIJA includes $3.7 billion for DAC hubs, nearly $260 million for DAC research, and $100 million for commercially viable CDR projects. A tax credit that implementing partners helped enshrine back in 2018 — amplified under the IRA — has spurred an additional $912 million in DAC investments, which will continue to grow thanks to recent enhancements.

Philanthropic support has also catalyzed private investment in DAC. For example, a ClimateWorks research grant helped Heirloom publish research that eventually helped to establish the first DAC facility in the United States. The facility runs entirely on renewable energy and was constructed with union labor. Additionally, Heirloom does not accept investment from oil and gas companies, which aligns with the company’s principles to center trust and equity. Meanwhile, Heirloom has adopted a community governance model in Tracy, California, where the facility has created a slew of green jobs. In 2023, Microsoft invested in Heirloom in one of the largest carbon dioxide removal deals to date.

ClimateWorks also supported the beginnings of private sector efforts to procure carbon removal. Today, the Frontier Fund, which began as a DAC buyer’s club supported by philanthropy, represents a $925 million commitment from companies like Meta, Shopify, Google, and Stripe to support carbon removal.

Advancing people-centered approaches to designing DAC projects

Philanthropy has supported efforts to help ensure the just and equitable implementation of DAC hubs without the involvement of the oil industry. The Community Alliance for Direct Air Capture (CALDAC), for example, is a coalition of research organizations, universities, technology companies, and community partners that is developing a community-led model for creating DAC hubs.

CALDAC works in California’s Central Valley, where the local workforce is already experiencing climate disruption, an unstable agricultural economy, and the worst air quality in the country. To understand how DAC hubs can contribute to a just transition for county residents, CALDAC convenes with community members to prioritize job creation, economic revitalization, and air quality improvement. Recent research shows DAC hubs can harness the same skill sets as oil and gas industry work, requiring little retraining and preserving high-paying jobs as oil companies abandon regions historically dependent on the industry.

CALDAC’s community-led model has garnered support from Central Valley residents and received a $3 million federal grant to further develop a replicable model for projects across the United States. Project 2030, a member of the coalition, also conceived of and sponsored a bill in California that requires DAC and other carbon capture projects to consider local safety and concerns, and bans its use for extracting more oil. This is the first regulatory foundation for governing the safe deployment of these technologies and can serve as a model for other U.S. states and beyond.

“Our conversations with community members show that many believe that DAC hubs present the opportunity to build not only climate-critical infrastructure but also economic and social opportunity,” says the research team from Data for Progress, a CALDAC member organization. “If done correctly, they can be a source of new partnerships, bridging climate-aligned industries to restore trust, repair damages, create new and attractive jobs with transferable skills from industries that are being phased out, and contribute to climate justice.”

Collaborating across sectors on decarbonization efforts

As the DAC industry evolves, philanthropy is helping build coalitions across sectors to advance DAC technology in a way that prioritizes community health, jobs, and decarbonization. For example, ClimateWorks’ CDR program collaborates with the aviation sector to explore DAC-derived aviation fuel, reducing dependence on the oil industry to scale the technology. This alternative jet fuel can lower aviation’s fuel-related emissions by as much as 90% and reduce fine particles that have caused respiratory illness for decades in airport-adjacent communities such as Oakland, Inglewood, and Compton in California.

In the largest deal for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) to date, airline companies British Airways, Iberia, and Aer Lingus have committed to purchasing 785,000 total metric tons of DAC-derived jet fuel from Twelve over the next 14 years. Twelve, a ClimateWorks partner, also broke ground on a new facility in 2023 that will produce 1 million gallons of DAC-derived jet fuel annually to supply American Airlines and other airline companies.

Collaborative research and advocacy from environmental groups, airlines, and cities have led to laws that require the development of SAF, creating a positive policy environment for DAC-derived fuels. In the European Union, aviation companies convened with research institutions and environmental groups through the Fuelling Flight Initiative and worked collaboratively to set the vision and guardrails for the SAF regulation that was approved in 2023. Thanks to coordinated advocacy, this regulation now prohibits alternative fuels that exacerbate deforestation or biodiversity loss — like those derived from palm oil.

The road ahead

This decade is pivotal for the future of CDR. Developing CDR technology today in parallel with ongoing efforts to reduce emissions is crucial for limiting additional warming in the latter half of the century.

As a result, much more philanthropic funding and engagement on CDR is needed — including for technological solutions, which remain significantly underfunded. In addition to reducing emissions, the world will still need to remove 10 to 20 gigatons of CO₂ every year until 2100. One study found that meeting Paris Agreement targets will require scaling up technological CDR solutions by a factor of 1,300 by 2050.

Philanthropy can help ensure CDR solutions including DAC scale responsibly with justice and equity at the center. Funders can continue to share findings across sectors, support enabling environments that lower costs, and create opportunities for expanding technological CDR efforts globally. To learn more, funders can contact ClimateWorks, explore resources on CDR, attend regional events, and read about CDR’s role in addressing climate change.

The Global Stocktake calls for bold climate action now. Its technical findings — the result of a nearly two-year process — offer a roadmap outlining how countries can course correct to achieve a zero-carbon and climate-resilient future that leaves no one behind. Now, it’s time to pick up the pace.

Bold climate action means transforming all global systems this decade — from how we grow our food to how we power our lives, transport goods, and build our cities. The Global Stocktake’s final outcome text included a historic agreement to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems” and critical signals for action across sectors to protect the world’s forests, boost zero-emission transportation, and reduce methane.

The next crucial opportunity for governments and United Nations Parties, as well as non-Party stakeholder groups, to move faster on climate action will be developing national climate action plans, which will include new or updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). Countries must submit these plans in 2025 — and the work begins now.

So what comes next for Parties, non-Party stakeholders, and the Global Stocktake process now that the outcome text has been released?

Next steps for Parties

Parties — the 198 governments and UN member states that have ratified the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) — must implement bold national targets and policies to deliver on the Paris Agreement goals. They must align domestic policies with these targets and increase international collaboration to drive action rooted in the findings of the Global Stocktake. Parties will participate in the following four activities before the next Stocktake begins.

- Governments must submit new NDCs in early 2025, which map out emissions reduction plans through 2035. This period is a crucial window for global climate action to catch up with the pace of change needed to stay within 1.5º C of warming (2.7º F) and transition to a safer world for all.

- Governments must solidify National Adaptation Plans by the end of 2025 and make progress on implementation by 2030. As of December 2023, with the 28th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP28), 51 Parties had submitted national adaptation plans. Now, countries must tailor their adaptation plans to national and local circumstances, and others must develop theirs. Developing these plans can draw upon the best practices and outcomes identified in the Global Stocktake. Support from non-Party interest groups, including the iGST community, will be crucial in getting the remaining plans over the finish line.

- Beyond commitments to the UNFCCC, Parties must integrate the Global Stocktake’s conclusions into national policies that aim to close gaps in adaptation, mitigation, and finance, in light of equity and the best available science. Globally, Parties have agreed to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030, transition away from fossil fuels, and pursue other key developments in forest protection, zero-emissions transportation, and methane. These agreements should be transformed into domestic policies that strategically align with their NDCs to ensure the efficient implementation of updated climate action plans ahead of their delivery.

- The conference presidents from COP28, COP29, and COP30 must collaborate to implement cohesive climate action between conferences. For example, the United Arab Emirates presidency (COP28) and the upcoming Azerbaijan (COP29) and Brazil (COP30) presidencies aim to maintain the momentum of international cooperation and ambition through their Road Map to Mission 1.5. As countries set new climate commitments for 2025, the partnership provides a platform for the three presidencies to collaborate on implementation and encourage the course correction called for in the Global Stocktake.

Next steps for non-Parties

Non-Party stakeholders — including cities, states, businesses, investors, and civil society — play a crucial role in supporting the effective and equitable implementation of climate plans and holding leaders accountable for their progress. These stakeholders identify gaps and areas of improvement. They are also central to ensuring governments develop just policies that center local communities and equitable solutions.

- Civil society plays a crucial role in translating the Global Stocktake outcomes. Civil society is crucial to helping governments understand how economic, social, and political situations impact how to implement adaptation and mitigation plans. Local civil society leaders and experts can ensure transparency in delivering on climate progress through their insights into local challenges and advantages. Civil society is also uniquely positioned to pressure governments to design policy interventions that achieve the speed, scale, and scope required to meet the climate emergency.

- The private sector, sub-national jurisdictions like cities and states, and civil society have the power to take voluntary actions informed by the Global Stocktake. For example, the outcome text of the Global Stocktake calls for “new and innovative sources of finance” to encourage and fund sustainable solutions. These new funding flows supplement the finance the Parties can provide, filling essential gaps. Multilateral development banks, international and domestic financial institutions, and private companies all have access to novel forms of finance that must be tapped to close the implementation gap.

Overall, acting on the findings of the Global Stocktake will require a whole-of-society approach incorporating voices from across sectors and industries to deliver a just transition and economic resilience in the face of a rapidly changing climate.

The second Global Stocktake in 2028

The next Global Stocktake will be completed in 2028. Refining the two-year process before the next cycle begins in 2026 is imperative.

- Parties and non-Parties must provide formal feedback on the Global Stocktake process. This feedback should help improve the different elements and parts of the Global Stocktake process, such as the technical dialogues and reports.

- Countries must record their greenhouse gas inventories in line with the Paris Agreement. This accounting will be done through the enhanced transparency framework, which is being fully implemented in 2024 and builds on UNFCCC standards for monitoring, reporting, and verifying emissions. This key component of the Paris Agreement will provide a much more detailed and comprehensive assessment of progress in time for the second Global Stocktake process to begin in late 2026.

Next steps for global climate action

While the final political outcome of the Global Stocktake is a major step toward driving deeper progress on climate, now is the time to translate these commitments into concrete actions across regions. The conclusion of the first Global Stocktake creates a moment to deliver vital commitments from countries through ambitious NDCs and NAPs in 2025. Most importantly, they must implement these commitments and set the world on an accelerated path to decarbonization.

The next steps outlined here provide an opportunity to demonstrate how adaptation, mitigation, and finance solutions rooted in equity and the best available science can deliver transformational change. Parties cannot and will not achieve progress in silos; non-Party stakeholders and civil society groups need to engage in domestic political processes to maintain pressure on national leaders and uplift local knowledge and solutions to ensure the equitable design and implementation of policies.

In this decisive decade for climate action, every year counts. All those involved in the writing and implementation of the Global Stocktake must use it to its potential to create a consistent cycle of progress for a brighter climate future.

Philanthropy came together at a remarkable pace to launch the Global Methane Hub — driving significant momentum for rapid action on reducing methane emissions.

In 2021, the European Union and the United States announced the Global Methane Pledge, inviting world leaders to reduce their countries’ methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030. This landmark Pledge came as a result of collaboration between governments, civil society, and philanthropy.

Since then, there has been remarkable global momentum for efforts to reduce methane emissions. As of February 2024, 155 countries have joined the Pledge, representing 70% of the global economy and half of human-caused methane emissions. In 2023, the European Union and the United States adopted their first-ever methane emissions regulations. And in December 2023, 50 top oil and gas companies pledged to reduce methane leaks from their production lines to “near zero” by 2030.

Methane has historically been overlooked in global conversations about climate change. However, the potent greenhouse gas is responsible for 30% of global temperature rise since the Industrial Revolution. Driven largely by the agricultural, fossil fuel, and waste management industries, methane is 84 times more powerful than carbon dioxide in warming the atmosphere over a 20-year period.

Cutting methane emissions could have an immediate impact and represents one of the most cost-effective ways to rapidly reduce the rate of global warming. “Quickly mitigating methane would be like hitting the emergency brake on global warming,” said Marcelo Mena, CEO of the Global Methane Hub. “Methane is the quickest way to decrease the temperature to buy time to address other dangerous pollutants.”

How philanthropy helped bring methane to the forefront

When the Global Methane Pledge was launched in 2021, more than 20 philanthropies committed an initial $223 million to support participating countries in implementing their promises to reduce methane emissions. This led to the formation of the Global Methane Hub to coordinate the distribution of the funds. Philanthropy has mobilized around landmark international agreements before — and it came together at an unprecedented pace to launch the Global Methane Hub, driving significant momentum for funding.

From 2015 to 2019, total foundation giving for super pollutants averaged $25 million annually, according to ClimateWorks Foundation data. Following the launch of the Global Methane Pledge, foundation funding to reduce emissions from super pollutants jumped to around $120 million in 2022, making it the fastest-growing sector that year. This included $70 million granted through the Global Methane Hub. However, the sector still accounts for less than 4% of foundation funding for climate change mitigation.

Here are five ways philanthropy has supported efforts to reduce methane emissions.

Expanding the evidence base for reducing methane emissions

Philanthropy has supported research that has helped make once-invisible methane emissions visible. Research published by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) between 2013 and 2018 showed that methane emissions were 60% more prevalent in the United States than the Environmental Protection Agency estimated. The research has since informed state and federal policies in the United States and beyond, leading to new technologies to reduce emissions and company commitments to prioritize methane reduction.

Philanthropy has also outlined cost-effective pathways for reducing emissions. As research from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and EDF has shown, the technology and the strategies already exist for reducing methane emissions from oil and gas operations by more than 75% — two-thirds of it at no net cost. The benefits of cutting methane this decade far outweigh the costs, according to the United Nations Environment Programme and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC). In fact, rapid and widespread efforts could slow the rate of global warming by as much as 30% and avoid 0.2° C of warming by 2050, according to research led by EDF.

Building awareness of methane leaks and health impacts

Philanthropy has equipped advocates with the data and the means to communicate methane-related issues to the broader public. For example, Earthworks and the Clean Air Task Force (CATF) have used infrared cameras to investigate leaks at oil and gas extraction sites, revealing discrepancies in company-reported emissions data and leading to policy change. Earthworks also maps public health threats from oil and gas production.

With this data, Climate Advocacy Lab helps advocates optimize their public engagement campaigns and the Methane Partners Campaign pushes for national methane pollution standards. Media campaigns like CATF’s #CutMethaneEU and Climate Nexus’ Gas Leaks have helped bring international attention to health impacts associated with emissions, leading to press coverage and further action.

The Global Methane Hub carries on this work as it facilitates people-centered strategies across sectors. “The only way for methane solutions to succeed is if they bring local benefits,” said Mena. “We do it because it’s in the best interest of people and because of the multiple development gains that can be achieved.”

Driving policy change

Philanthropy has contributed to policy wins that will help reduce methane emissions. Using resources like CATF’s Country Methane Abatement Tool, an estimated 90% of the 195 countries participating in the Paris Agreement have incorporated methane reduction targets into their climate goals. 57 of these governments have gone further to develop methane-specific roadmaps — 31 supported by the CCAC, a grantee of the Global Methane Hub.

CATF also facilitates capacity-building workshops as governments develop targets, including Nigeria, the first African country to regulate methane emissions from its oil and gas sector. Meanwhile, leadership from Navajo and Pueblo tribal advocates and local NGOs in New Mexico led to some of the strongest methane regulations in the United States, influencing policies at the national and international levels.

Philanthropy is also facilitating peer-learning opportunities for leaders across sectors through efforts like the Global Methane Initiative. Regulatory roadmaps from IEA and CATF, as well as policy input from EDF, have already led to requirements for oil and gas operators to fix methane leaks in Canada, Mexico, the United States, and the European Union. The rule in the United States could reduce as much greenhouse emissions in 2030 alone as taking 28 million gas-powered cars off the road for the entire year.

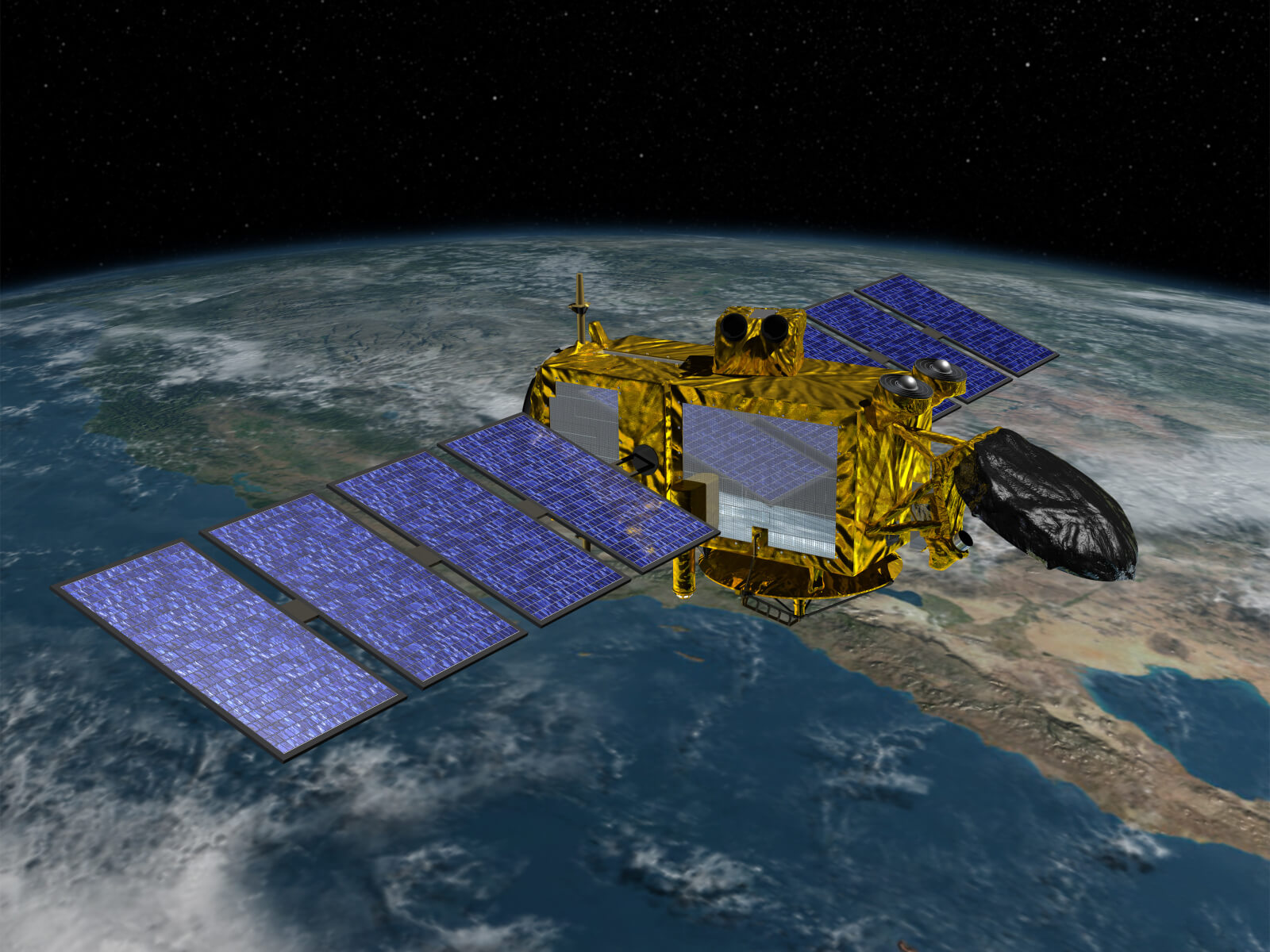

Scaling accountability capabilities across sectors

Philanthropy has supported the development of tools to help enforce methane regulations, and the Global Methane Hub’s coordinated approach has helped accelerate these efforts. Indigenous and local advocates are using tools from Earthworks and EDF to monitor methane emissions. Meanwhile, the MethaneSAT and Carbon Mapper satellites will make it faster and more affordable to track leaks and landfill emissions, respectively.

The Methane Alert Response System (MARS) uses this new infrastructure to send notifications of major leaks to governments and companies as they are detected. Already, the state of California is incorporating this satellite technology into its Methane Accountability Program. In February 2024, Google announced a partnership with EDF to map methane pollution and oil and gas infrastructure from space.

Another innovative effort is the Waste Methane Assessment Platform (WasteMAP), an open-source tool that consolidates methane emissions data from the waste sector to identify reduction opportunities. 20 mega-cities representing more than 135 million people have connected to the platform since its launch in December 2023.

Philanthropy has also supported the development of accountability frameworks to put pressure on oil and gas companies. The Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0, developed in part by EDF, offers an emissions reporting framework already signed by 62 companies that represent 30% of the world’s oil and gas production.

Unlocking public, private, and Multilateral Development Bank (MDB) funding

Through its collaborative approach and global strategy, the Global Methane Hub has successfully unlocked additional funding for methane solutions and increased philanthropic engagement with leaders in the Global South. “We see the climate problem through an integrated, developmental lens,” said Mena. “And we bring others along in that vision.”

The Global Methane Hub has also provided accelerator support to launch multilateral initiatives. For example, with the Hub’s support, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) developed its Too Good to Waste Initiative. The effort will steer a roughly $350 million portfolio to avoid additional waste-related methane emissions in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Hub also helped catalyze a $500 million investment from the UN’s International Fund on Agriculture Development (IFAD) and a World Bank initiative to end flaring.

Overall, global financing for methane abatement increased by 18% following the Global Methane Pledge, totaling $13.7 billion from 2021 to 2022. In 2023, commitments from Global Methane Pledge partners reached an all-time high of $1 billion, more than tripling from the year before. Nonetheless, there is room for growth, as support for methane reduction still accounts for less than 2% of global finance for climate change mitigation.

The road ahead

While there is encouraging progress on reducing methane emissions, much more funding is needed to build on this momentum. The Climate Policy Initiative estimates the need for at least $48 billion in global annual investment — 3.5 times current levels — between now and 2030 to meet global methane targets. Now that the world is starting to pay attention, those targets are potentially achievable.

“The work we do is so critical,” said Mena, “not just for rolling back the clock on the global temperature rise, but for creating a better and more sustainable way of living for billions of people around the world.”

To learn more, funders can explore funding priority areas identified by EDF and the Global Methane Hub, along with newer initiatives focused on researching agricultural methane emissions, phasing out super pollutants, developing accountability frameworks, and addressing waste. Funders can also contact ClimateWorks for support in building an effective climate strategy.

The UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai marked a historic step forward when the final text of the Global Stocktake included language on fossil fuels. The Global Stocktake is a UN-led process that gives the world a clear review of global progress and shortcomings on climate action and rallies world leaders to raise their ambition. Throughout COP28, media coverage was dominated by speculation over how the agreement would address fossil fuels. Ultimately, the Global Stocktake included a call to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems.” The release of the final text sparked debate over whether this phrasing was a significant accomplishment or a decision that fell short of what was needed. However, amid the discourse around fossil fuels, renewable energy commitments, and COP politics, the Global Stocktake also included several significant wins that were overlooked.

In the two years leading up to COP28, the governing body overseeing the Paris Agreement and Global Stocktake produced global technical assessments of climate action and hosted exhaustive and inclusive discussions with country delegations and civil society actors. These dialogues aimed to accelerate progress in mitigation, adaptation, and means of implementation and support — all in light of equity and the best available science. The final text, released at COP28, sets the pace of change for the next two years as countries develop new national climate action plans — including Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) — ahead of the 2025 submission deadline.

Energy systems, and therefore fossil fuel use, comprise only a fraction of the most essential takeaways from the Global Stocktake. Thanks to tireless input from iGST members and other global advocates, the final text highlights other crucial outcomes that received less publicity — such as the importance of conserving, protecting, and restoring nature; decarbonizing the transportation sector; and reducing methane emissions. These outcomes are crucial pieces of the climate puzzle to achieve a more sustainable world.

A new era of global forest protection

Coming out of COP28, the final text of the first Global Stocktake recognizes the critical need to conserve, protect, and restore nature and ecosystems. It emphasizes enhanced efforts to halt and reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030. Additionally, it highlights the importance of financial investments supported by policy incentives to promote conservation and sustainable forest management.

The inclusion of this priority is especially important given the impacts of rapid degradation and deforestation globally. Despite global commitments to forest protection, the tropics lost 10% more primary rainforest in 2022 compared to 2021, according to the Global Forest Watch. The loss of tropical, old-growth forests in 2022 totaled 4.1 million hectares, emitting 2.7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide, equivalent to India’s annual fossil fuel emissions.

The language of the final text underscores the contributions forest conservation and protection efforts can make toward achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goal of keeping global warming well below 2° Celsius. Moreover, it highlights the people-centered co-benefits of halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation, including accelerating sustainable development and eradicating poverty.

A boost for zero-emission transportation

The transportation industry — including aviation, maritime shipping, and road transport — requires steep decarbonization, as most transport still relies on fossil fuels. Overall, carbon dioxide emissions from transportation have increased by more than 70% since 1990. The industry now accounts for more than 20% of fossil fuel-related CO₂ emissions worldwide, underscoring the need for zero-emission transportation.

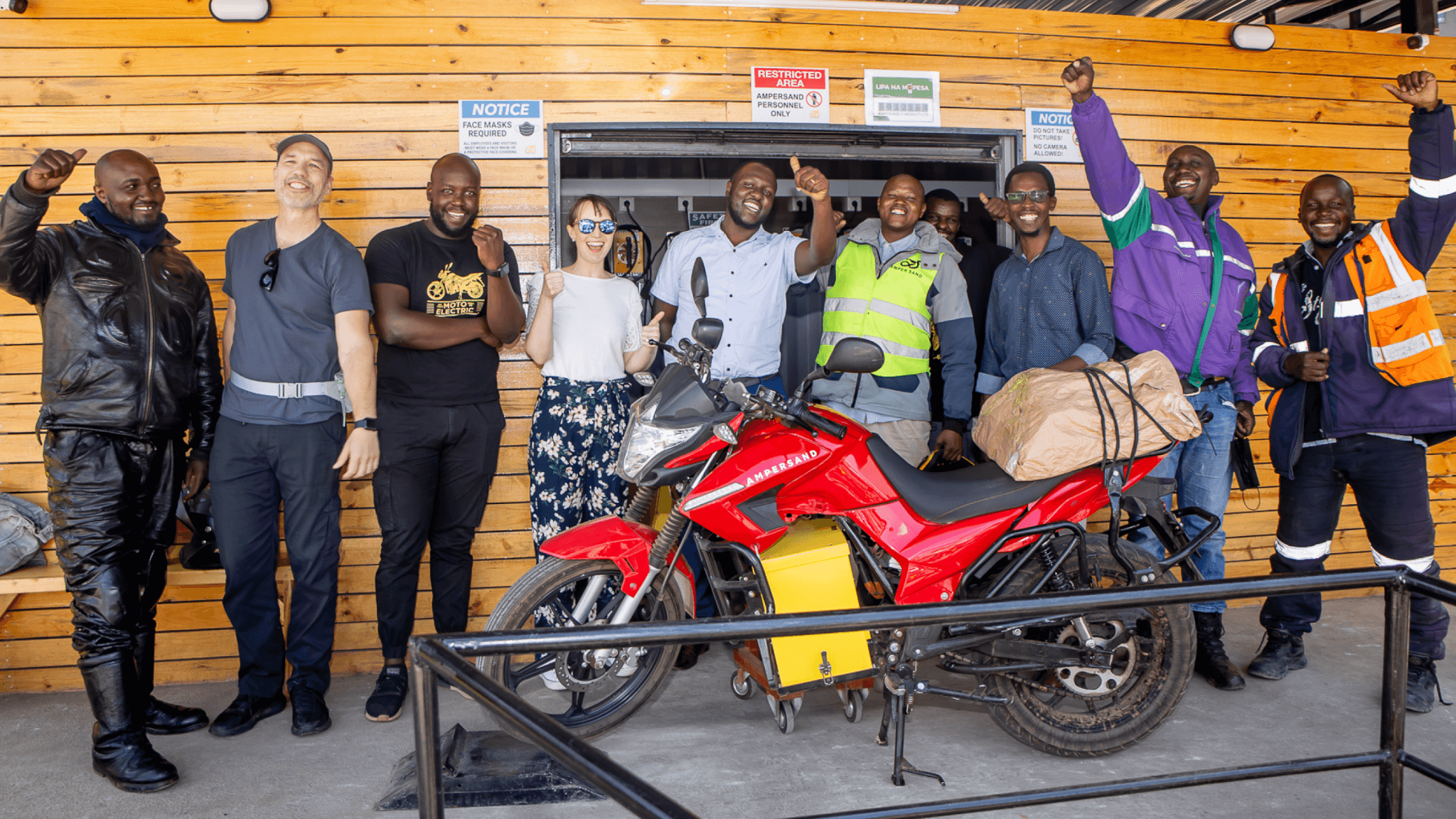

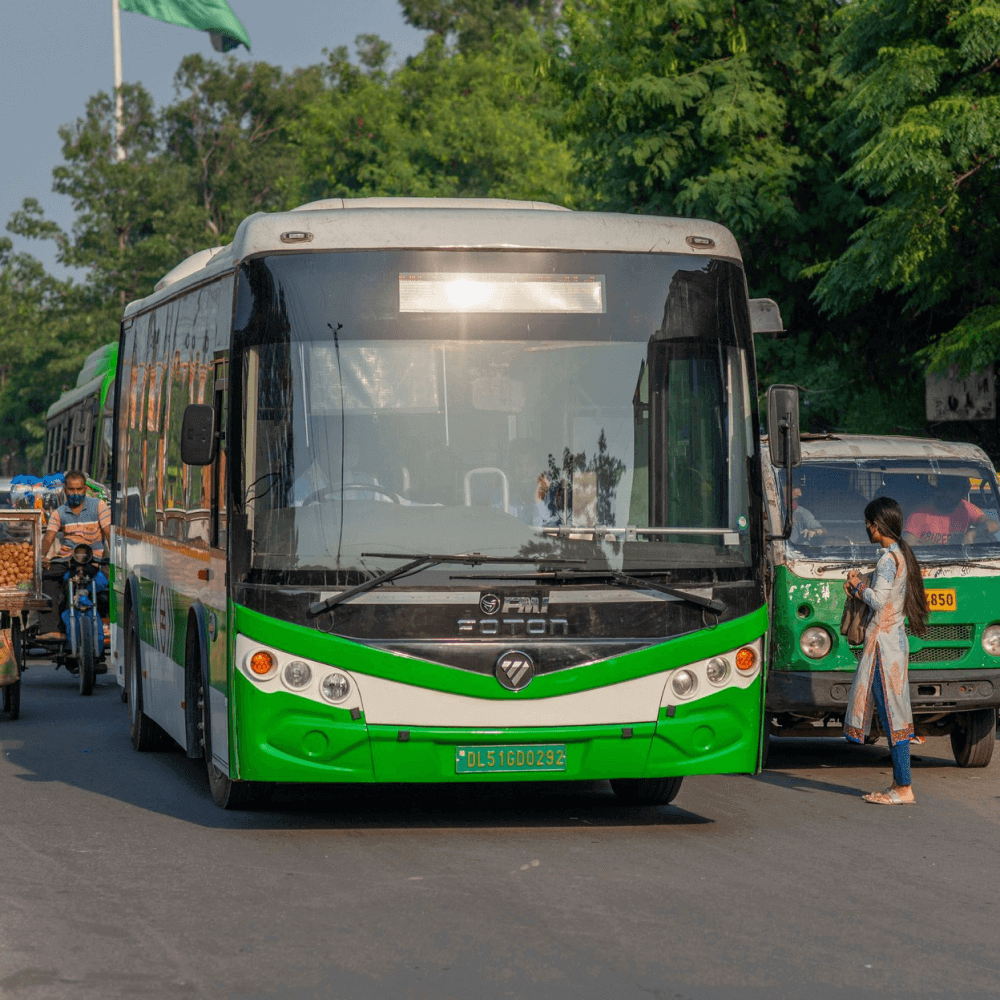

The Global Stocktake’s call to decarbonize the transportation sector accentuates, once again, the importance of transitioning to electric vehicles (EVs), scaling infrastructure, and investing in clean fuels for the maritime shipping and aviation sectors. This transition requires a global effort to recognize and address the need for energy and resource efficiency in the transport sector. Collaboration across sectors is also necessary to achieve the policies and investments that will transform the road transportation industry. To deliver the goals of the Paris Agreement, the world needs to swiftly embrace zero-emission transportation, as recognized by the outcome of the first Global Stocktake.

Public and private sector leaders in emerging economies are already seizing the opportunity to transition to EVs to create and shift local jobs, reduce pollution, and solidify their roles in the global supply chain. Supporting local leadership will be key to decarbonizing the transportation sector. In addition, increasing funds for clean fuel research and development can boost the green transition for the maritime shipping and aviation industries.

Addressing the problem of methane

Methane has often been overlooked in the global sustainability conversation, even as scientists have repeatedly called for the radical reduction of methane emissions. In the United States, research conducted by the Environmental Defense Fund found that the U.S. oil and gas industry was emitting at least 13 million metric tons of methane a year — about 60% more than the Environmental Protection Agency estimated at the time. This finding underscores the significance of the Global Stocktake’s inclusion of methane in its call to action, putting additional pressure on the fossil fuel sector to address its emissions issues. Moreover, the International Energy Agency estimates that emissions in the energy sector are underreported by 70%, which makes identifying methane leaks and the lack of transparency around these emissions a global problem.

In addition, according to the International Energy Agency, agriculture is the largest anthropogenic source of methane emissions. The Global Stocktake’s emphasis on building sustainable land-use management and agricultural practices reinforces the importance of reducing the environmental impacts of these activities, particularly non-carbon emissions like methane.

The final Global Stocktake text highlighted the need for methane emissions reductions, which supported the Global Methane Pledge announced at the conference in 2021. World ministers welcomed transformational national actions and catalytic grant funding to help countries achieve at least 30% methane emissions reduction by 2030. Commitments and language in the Global Stocktake are a first step; countries must now implement policies that will deliver on their promises to reach the 30% goal by 2030, as time is quickly running out.

A multi-sectoral approach to accelerate climate action

The call to world leaders is clear after this first Global Stocktake. Across the globe, the public and private sectors must work together to invest in clean technology, protect our natural resources, and swiftly eliminate our reliance on fossil fuels. The road to COP29 and COP30 requires unprecedented political will as countries develop new climate action strategies through NDCs and NAPs. The following two years provide a unique and critical opportunity to accelerate action on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving resilience and adaptive capacities, and ensuring adequate and available finance. Furthermore, the Global Stocktake stresses the importance of including local communities and experts while planning and implementing multi-sectoral strategies to ensure all voices are included when deploying solutions for a sustainable future.

Getting cooling right would save thousands of lives every year and reduce food loss — and could prevent 100 gigatons of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, equivalent to two years of global emissions.

As climate change continues to drive record-breaking temperatures and heat waves, the safety and livelihoods of billions of people are increasingly at risk. Currently, more than 1.1 billion people in rural and urban communities are at risk due to lack of access to cooling, which makes it more difficult to stay healthy, learn and work productively, and keep food and medicines at safe temperatures. One thing is clear: access to cooling is no longer a luxury — it is a human right.

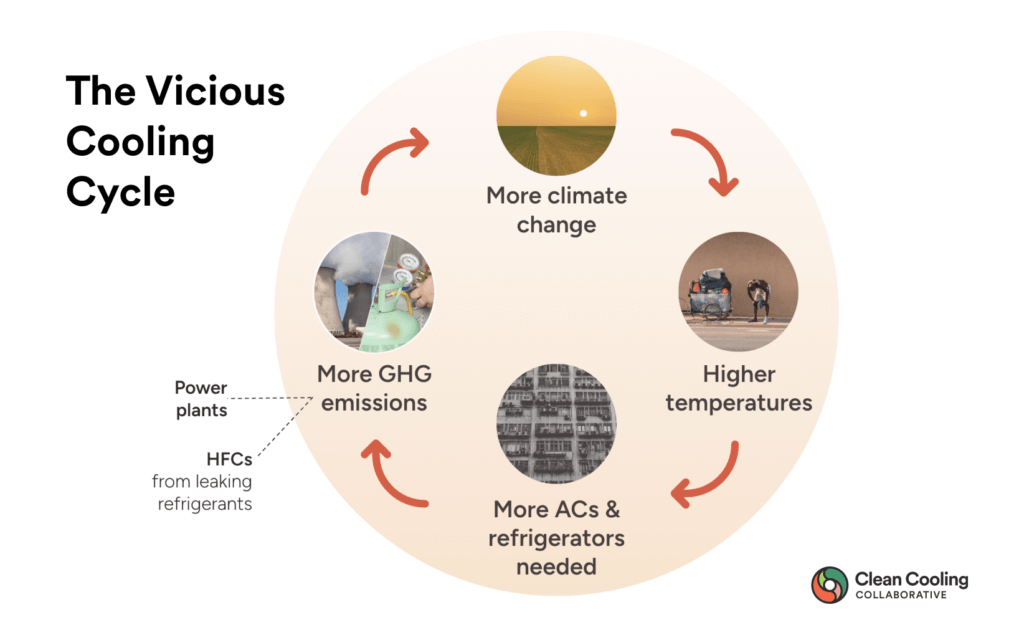

Global energy demand for cooling is expected to triple in the coming decades, according to the International Energy Agency. The roughly 2 billion air conditioning units in use today are already top drivers of global electricity demand. By 2050, 3 billion more units are projected to be in operation. Without energy efficiency improvements, this growth in the number of cooling appliances would lead to as much electricity use as all of China and India today. This increase would further stress electricity grids, which in turn could contribute to more blackouts and brownouts, as well as drive the use of heavy-polluting fossil fuel-based peaker plants.

The growing global demand for cooling contributes to what has been described as the “cooling conundrum.” As the planet gets warmer, demand for cooling goes up. Also, as populations continue to grow, more air conditioners and refrigerators are installed. These cooling technologies add billions of tons of planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions like carbon dioxide and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) to the atmosphere due to their energy consumption and refrigerant leakage. “It’s a vicious loop,” says Sneha Sachar, India Cooling Lead for ClimateWorks Foundation’s Clean Cooling Collaborative (CCC). “We cool the indoors, but we warm the outdoors, therefore generating the need for yet even more cooling.”

Over the last few decades, science, policy, diplomacy, and technology have teamed up to respond to the cooling challenge. Collectively, these efforts contributed to the signing of the Kigali Amendment in 2016. This was an amendment to the landmark Montreal Protocol, a global treaty that entered into force in 1989 and banned chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), greenhouse gases that caused the depletion of the ozone layer. The Kigali Amendment, in turn, committed to a phasedown of the production and consumption of HFCs, which had largely replaced CFCs as the refrigerant used inside air conditioners and refrigerators following the implementation of the Montreal Protocol. If implemented fully, this HFC phasedown could avoid up to 0.4° C in global temperature increases by 2100.

To deepen impact and further reduce emissions, climate leaders have made efforts to get manufacturers to simultaneously incorporate energy efficiency improvements in their cooling technologies as they redesign their production lines and products to switch to more climate-friendly refrigerants that have much lower global warming potential. This unprecedented pairing of strategy for efficiency improvements with the HFC phasedown has set a tone for more collaboration in global clean cooling efforts.

Years later, we continue to see more integrated approaches to tackling cooling. For example, the Global Cooling Pledge was launched and announced at the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in December 2023. In a major international collaboration, led by the UN Environment Program’s Cool Coalition and UAE COP28 Presidency, more than 60 countries to date have committed to take immediate steps to improve the sustainability of cooling appliances, scale passive and mechanical clean cooling efforts, and increase access to clean cooling for those most at risk in a warming world.

How philanthropy has bolstered progress for clean cooling

Philanthropy has played an active role in advancing clean cooling initiatives. In 2017, 18 leading climate funders recognized an opportunity around the adoption of the Kigali Amendment. Together, these funders established the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (K-CEP), which laid the initial groundwork for a cross-cutting, focused approach to advance clean cooling.

Housed at ClimateWorks Foundation, K-CEP initially pooled $52 million to support low-income countries as they paired their HFC phasedown activities with improved energy efficiency opportunities for various categories of cooling appliances. In 2022, the program’s name and strategy areas evolved to become the Clean Cooling Collaborative (CCC), focusing on regions that are projected by the International Energy Agency to have the highest contribution to cooling-sector-related GHG emissions over the next 30 years (China, India, Southeast Asia, and the United States). CCC takes an intersectional approach, working to reduce the cooling sector’s greenhouse gas emissions; increase access to efficient, climate-friendly cooling for heat-vulnerable communities; and continue elevating clean cooling on the international agenda.

K-CEP and CCC’s grants have created an enabling environment for clean cooling to scale, and many of those grants have created ripple effects of impact. For example:

- More than 100 countries have built cooling-specific policies into their national climate strategies or Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) — work that will only deepen with the more than 60 countries who have signed the Global Cooling Pledge thus far.

- 30 countries have developed energy efficiency policies or standards for cooling appliances to ensure that every new air conditioner and refrigerator sold meets a minimum level of efficiency. This will help prevent countries in the Global South from becoming the dumping ground for the least efficient products on the market that can no longer legally be sold elsewhere.

- More than 1.1 million square meters of new, solar-reflecting “cool roofs” have been installed globally as part of the Million Cool Roofs Challenge — an area equivalent to 250,000 small household rooftops.

Ultimately, building on the foundations laid by K-CEP, CCC works at many levels of the global cooling agenda, acting as a hub to catalyze research and demonstrations, policy, finance, and market transformation. CCC has created a community of more than 30 grantees from around the world and hosts an annual convening of its grantees and funders to exchange updates on successes, new opportunities, and ways to jointly accelerate change in this space.

These are some of the levers that philanthropy has used to make an impact in the cooling space:

Identifying opportunities and sparking innovation

In the early days of K-CEP, the importance of expanding access to cooling was clear — but just how many people lacked that access wasn’t yet quantified. Some of the initial investment went toward defining the gaps within policy, technology, and finance, along with the opportunities to address them. Building country-specific political and economic awareness became essential for future work to raise cooling access.

K-CEP and its partners also facilitated prizes and competitions that illustrated the efficacy of emerging cooling solutions and incentivized the development of new ones. For example, the Million Cool Roofs Challenge helped scale the adoption of passive cooling strategies, which reduced indoor temperatures by a few degrees Celsius and led to global recognition.

CCC continues this work to transform markets that enable wide-scale deployment of efficient, climate-friendly cooling solutions. The CCC-led Global Cooling Efficiency Accelerator, for example, builds on the work of the Global Cooling Prize (an initiative of RMI, the Government of India, and the United Kingdom’s Mission Innovation) to bring to market super-efficient room AC prototypes that have a five times lower climate impact than the average model today. According to an analysis from RMI, a shift to room air conditioners that deliver this superior efficiency and use more climate-friendly refrigerants can prevent up to 5,900 terawatt hours of electricity per year by 2050 — the equivalent of two times the annual electricity generated within the European Union.

Removing financial barriers to the clean cooling transition

Philanthropy can support the piloting of financial incentives and business models that encourage consumers, service providers, and companies to reach for more energy-efficient options. For example, K-CEP supported the roll-out of new business models like cooling-as-a-service (CaaS), where consumers pay for cooling or refrigeration on a per-unit basis, enabling commercial end users to access efficient technologies without the investment costs. On-bill and on-wage financing programs in Rwanda, Ghana, and Senegal have helped consumers overcome the higher upfront cost of energy-efficient air conditioners and refrigerators.

These days, CCC works to help markets transition to more efficient cooling strategies through the development of pilot demand response programs, which take stress off the electric grid during periods of peak power demand while crediting consumers for their reduced energy use. For example, a groundbreaking demand response program in China holds the potential to save consumers, businesses, and utilities significant expenditures while also reducing the likelihood and duration of power outages. The wider adoption of demand reduction initiatives in China could yield savings of $40 billion over a decade, primarily through the avoidance of having to build and operate additional power plants.

Convening and collaborating

Philanthropy has a unique ability to convene experts from across geographies and sectors. In 2017 and 2018, energy policymakers and Montreal Protocol compliance officers across 147 countries met in philanthropy-supported “twinning” workshops to build bridges between ministries, many for the first time. Then in 2019, K-CEP joined forces with the U.N. Environment Programme to launch the Cool Coalition, which aims to foster collaboration between governments, businesses, and civil society to advance efficient, climate-friendly cooling. These earlier efforts from K-CEP have led to the rapid scaling of best practices, the development of National Cooling Action Plans (NCAPs), and continued cooperation between actors.

“I had been working on energy efficiency for 25 years and it never occurred to me to team up with the ozone people,” said Mirka della Cava, Head of Policy for CCC, about why she spearheaded K-CEP’s support of these early workshops. While agencies continue to benefit from ongoing dialogue on the linkages between refrigerant transitions and energy efficiency, the work that K-CEP supported on the development of NCAPs is an example of how national ozone units successfully prepared approaches to achieving more efficient cooling, often outlining specific measures such as minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) for cooling products.

Now, CCC builds on this legacy of cooperation as they support countries working together toward the common goals articulated in the Global Cooling Pledge.

Influencing policy by defining best practices

Through both K-CEP and CCC, ClimateWorks’ cooling program has helped foster a global ecosystem built upon the sharing of best practices by collaborating with local arenas and learning from their implementation and expertise. The development of model policies by CCC’s grantees offers a customizable framework for countries to establish MEPS. These templates provide best practice guidelines for what actions are needed to transition to more efficient cooling appliances. From there, countries can take into account their region’s markets.

CCC’s support for this emerging community of practice has consolidated best practices and rapidly scaled up the development of effective policy — all in a way that aims to honor a wide range of local contexts around the globe. “You can’t skip over how the local context will embrace or realistically implement best practices,” says della Cava. “CCC and our partners have been asking ourselves: how can we create resources and models that can be picked up, adopted, and absorbed by a diversity of local actors?”

A partnership with Energy Foundation China successfully saw the implementation of new MEPS which resulted in variable speed ACs rapidly scaling in just one year, to represent 98% of the AC market — virtually eliminating its less efficient fixed speed counterparts that use roughly 35% more energy and saving consumers billions in reduced utility bills. Philanthropy-backed efforts have also enhanced the implementation of MEPS, as seen when CCC-supported workshops with Ghana’s Energy Commission led to the improved compliance of its efficiency labeling standard and enforcement for imported cooling products. As countries adopt these best practices, they inspire other regional efforts.

The road ahead

Announced at COP28, the Global Cooling Pledge marked a historic moment to raise international ambition for clean cooling. A growing list of countries (more than 60 to date) and non-state actors have signed the pledge and committed to taking immediate steps to improve the sustainability of cooling appliances, scale passive and mechanical clean cooling efforts, and increase access to clean cooling for those most at risk in a warming world. The cooling sector also released its first-ever stocktake report, outlining the potential pathways to cut cooling-related emissions by more than 60% by 2050 and expand cooling access to 3.5 billion people.

The global momentum behind cooling efforts is an encouraging step, made possible in part by a vast and growing network of climate funders, grantees, and partners around the world. Further progress will take significant additional investment. More funding is needed to build on this momentum, ensure the achievement of global commitments, and scale cooling access in a way that centers on those most impacted by a warming world. To learn more, funders can contact ClimateWorks and explore resources such as CCC’s solution areas, reports, and newsletter.

Philanthropy can help catalyze a shift toward more sustainable, just, and resilient systems, societies, and economies.

Imagine what the world could look like in 2050. Our power grids run on renewable energy. Everyone has access to the energy they need to cook, light their homes, and stay cool. Almost every coal plant and oil refinery on the planet has been retired. Electric public transport and cars take us where we need to go while keeping the air we breathe clean. Indigenous and local communities have the legal recognition and support they need to nurture healthy forests. The world has transitioned to a global green economy that enables healthy lives, good jobs for all, and a thriving planet.

In the words of the poet Lucille Clifton, “We cannot create what we cannot imagine.” That is why I’m proud to introduce ClimateWorks Foundation’s new series of impact stories, which spotlights a diverse and expanding community of global changemakers driving transformative climate action and illustrates how philanthropy has supported their efforts. Philanthropy is increasingly mobilizing to support bold climate action, as evidenced by the entry of more funders into the arena, a growing community of grantees, and a tripling of foundation funding since 2015. While the demands of the climate crisis are daunting, those implementing solutions on the ground give us reason to hope.

The time to act is now

The urgency has never been greater to replicate the climate successes supported by philanthropy as widely as possible. Climate change is not a distant concern but a current reality affecting communities worldwide. Global climate initiatives are falling short of Paris Agreement targets and philanthropic funding for mitigating climate change saw a disappointing plateau last year.

Even so, there is progress to celebrate and build upon. In 2014, our trajectory pointed to a planet 3.7° C warmer than pre-industrial levels by the century’s end. Current policies have successfully altered our course, positioning us toward an approximately 2.5° C rise. The progress so far is pivotal, but a future above 1.5° C of warming would still be catastrophic. More action is needed to accelerate climate solutions at the speed and scale that will ensure a healthy and equitable future for all.

The climate crisis calls for unprecedented collaboration among governments, the private sector, and civil society. Philanthropy is uniquely positioned to help catalyze the transformative shift we need toward more sustainable, just, and resilient energy and food systems, societies, and economies. Philanthropy can be risk-taking and nimble, trying different approaches and pivoting quickly in response to new challenges or opportunities. Philanthropy can convene disparate actors and mobilize resources for those implementing change on the ground in pursuit of a more prosperous future for all. Philanthropy is also able to both invest in long-term horizons and support immediate needs. Additionally, unlike the private sector, philanthropy is willing to invest for impact rather than financial return alone, supporting geographies where the need is highest and catalyzing additional investment from the public and private sectors.

A roadmap for driving bold climate action

Philanthropy has already played a significant role in supporting bold climate action — engaging with efforts to advance renewable energy, accelerate the adoption of clean transportation, advocate for Indigenous and local land rights, tackle super-pollutants, and achieve clean cooling for all. For example, since 2017, 57 countries have developed new policies and programs dedicated to climate-friendly, energy-efficient cooling technology based on models driven by the Clean Cooling Collaborative, a philanthropic initiative. With support from the Beyond Coal campaign, at least 40% of coal-fired power plants in the United States and 50% in Europe have been retired. Electric vehicles have taken off faster than expected, with exponentially growing sales in some of the highest-emitting regions. The Drive Electric Campaign, a network of more than 100 organizations around the world, has helped accelerate EV adoption in these regions by building political will and technical capacity. Philanthropy has supported efforts to elevate Indigenous and local community land rights on the global stage, leading to historic levels of support through the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities’ Forest Tenure Pledge announced at COP26. A growing carbon dioxide removal movement has received philanthropic support, which has helped the sector scale responsibly and thoughtfully. Philanthropy also helped shape the historic Inflation Reduction Act — the boldest climate action from the United States to date — and has a critical role to play in its implementation.

Our growing collection of impact stories, like the ones noted above, highlights the replicable, intersectional, and collaborative approaches that were essential to these philanthropic successes and others like them. We will continue to bring stories from people implementing change on the ground as well as both new and experienced climate funders mobilizing resources across a range of geographies. We hope these stories will illuminate the expansive efforts that have already driven climate progress and ultimately inspire the philanthropy community to keep pushing for even bolder action — individually, collaboratively, and with partners through innovative new efforts like the Giving to Amplify Earth Action (GAEA) Initiative, the IKEA Foundation’s Just Transition Fund, and the Philanthropy for Asia Alliance. Please stay tuned for more stories in the months ahead.

Reach out to us to share your success stories or to learn how you can contribute to advancing climate action, and read more climate philanthropy impact stories here.

Dear colleagues and friends,

2023 was blisteringly hot and earned the distinction of the hottest year on record. Yet, we know last year was not an outlier but rather a trend in the wrong direction, as the intensifying impacts of climate change create devastating consequences for people, communities, and ecosystems worldwide.

We are nearly halfway through the decisive decade for climate action, and we are off track in meeting global targets. The good news is there’s never been more progress to build on as we work to course correct. The backlash from the fossil fuel industry and other incumbents that we’re seeing on climate policies, organizations, and frontline leaders is, in some ways, a sign of the impact we’re having. As a community, we’ve stepped up to push back on some of these challenges — for example, developing legal defenses and durability strategies to ensure that environmental and social risks can be reflected in investment decisions, and rapidly responding to misinformation on the environmental impacts of electric vehicles. But there is more to do. Under the most optimistic scenario, the current likelihood of limiting global warming to 1.5° C is just 14%. Now is the moment for all of philanthropy to step up and work together and with others in groundbreaking new ways to supercharge transformative solutions in 2024.

Three strategic shifts for 2024

In 2024, we have an opportunity to build on the progress we’re seeing and accelerate action. For this year, here are three key areas where the global community can help the world move faster in turning promises into tangible actions:

Phasing out fossil fuels. COP28 signaled the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era. But the gap between what governments have committed to and what they are doing is vast. To truly transition the energy sector, we must both ramp up the good and phase out the bad. Thanks in part to bold philanthropic initiatives advancing renewable energy and electric vehicles, we are making great strides in increasing the good. Today, renewables are the cheapest form of electricity generation almost everywhere, and the adoption of zero-emission vehicles of all types (cars, trucks, buses, two- and three-wheelers) is growing exponentially.

But we must also tackle the other half of the equation — phasing out fossil fuels. COP28 provided an important hook, with text agreed in the Global Stocktake by all countries calling on parties to “drive the transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner.” Now is the time to seize this opening, building on developments like the United States’ recent decision to pause permits for LNG exports. One place to start would be advocating to end the more than $1 trillion in global fossil fuel subsidies — a new record high reached in 2022 — that directly undermine governments’ climate goals. Just imagine what we could achieve instead if these funds were applied toward expanding energy access through renewable resources and supporting a just transition for workers and communities. Now is the time to double down on transitioning away from fossil fuels, building on the recognition by all governments at COP28 of the need to do so.

Equitable and accessible financing of climate action. More funding and creative funding models are crucial not only to achieving mid-century net-zero goals but also to advancing climate justice for those most affected by climate impacts and least responsible for them. COP28 made important progress in operationalizing a new Loss & Damage Fund, and COP29 in Baku later this year will include a focus on international finance commitments. In addition, there is much happening outside the official UN space that has the potential to truly transform domestic and international finance and institutions, including transparently integrating climate risks and opportunities into the heart of public and private finance decisions.

We are entering a new era for sustainable private finance, where it is time to move from promising voluntary initiatives to regulatory approaches. One example is progress on corporate disclosure rules that will drive responsible business practices and benefit investors while also protecting people and the planet. Another important approach is the coordination of strategies for reforming the multilateral development banks (MDBs). Philanthropy is increasingly playing a role in working with partners to identify solutions, engage influential stakeholders, and advance action — while also confronting head-on pushback from the fossil fuel industry and lobby groups.

Ramping up implementation and ambition with inclusive climate solutions. We need to follow through on the current commitments and show how climate action truly benefits people, communities, and economies. By identifying climate solutions that positively impact people’s fundamental needs — how they provide for themselves and their families, safety and security, resilience, and health — and showing these benefits, we can gain support for bold, people-centered climate solutions that tackle interconnected challenges and are durable.

Getting implementation right now is essential to increasing the level of ambition going forward. As part of this, we need a greater focus on the sectors that have been neglected for too long and thus remain seriously underfunded — in particular, industry decarbonization, shipping, aviation, and food & agriculture. These are areas where ClimateWorks, with our partners, will be looking to step up action in 2024.

By COP30 in Brazil in 2025, countries are asked to update their national targets for reducing climate pollution. While this is a government-led process, it is increasingly clear that all parts of society must contribute to the solutions for the kind of ambition we need to see. This means greater involvement from sub-national actors, corporates, and the finance sector to align with the active participation already seen from academia and civil society. The importance of this next round of opportunities to raise ambition cannot be overstated, and philanthropy and partners must start engaging now with efforts to support the development of more ambitious plans.

The moment is now