No one knows what the world will look like in 2050, but we know profound changes lie ahead. The rapid decarbonization needed through 2050 will require transformational changes throughout the global economy. What might looking through a 2050 lens tell us about priorities for climate philanthropy globally? What seeds need to be planted now for future success?

Over the past decade, climate philanthropy has focused on seizing the best near-term opportunities to keep the rise in global temperatures to well below 2° C.

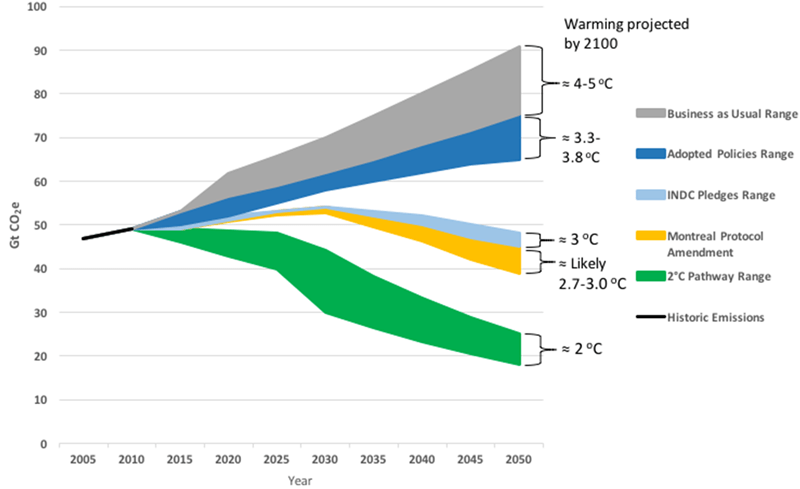

Recent progress is heartening, as philanthropy has played an important part in helping to reduce clean technology costs, lock in greenhouse gas emissions reductions, and protect key carbon sinks. We have made significant strides in transforming the power sector and the transportation sector, which are essential components of success. But there is a great deal more to do. Meeting our global climate goals will require net greenhouse gas emissions to peak by 2020, and will require a steady and steep decline through 2050, net-zero emissions sometime around mid-century (which will require carbon-dioxide removal), and negative emissions after that.

GHG Emissions Projections through 2050 (Approximate pathways for various reduction scenarios)

No one knows what the world will look like in 2050, but we know profound changes lie ahead. The rapid decarbonization needed through 2050 will require transformational changes throughout the global economy. What might looking through a 2050 lens tell us about priorities for climate philanthropy globally? What seeds need to be planted now for future success? With these questions in mind, ClimateWorks initiated a project to explore what the existing evidence tells us about how current philanthropic strategies and priorities might need to be adjusted or expanded if philanthropy is to do its part to sustain the long, crucial drive to decarbonization by mid-century.

It is difficult to predict what effect socioeconomic and geopolitical shifts will have on the landscape for climate action in the coming decades, but current trends suggest a variety of possibilities. ClimateWorks is exploring the disruptive effects a range of alternative futures would have on the framework within which climate advocacy and policymaking occur.

Our 2050 project is designed to be the beginning of a conversation with our colleagues and other experts in the field. We welcome your ideas as we continue to bring together diverse expertise to explore the effect that these shifts and trends might have on our priorities for climate action and for climate philanthropy.

2050: Preliminary Key Findings

Pursue global tipping points: Models predict the highest-emitting regions now may well remain the highest emitters in 2050. However, achieving a well-below 2° C future requires decarbonization worldwide. Given finite resources, philanthropy must selectively work in those geographies and prioritize those strategies that generate spillover effects or global tipping point opportunities. For many strategies, we need to determine the best ways to create global markets that can spread climate-friendly technologies and business models around the world.

Go all out for clean electricity: We must simultaneously decarbonize most power generation and convert energy end uses to electricity wherever possible. Some sectors such as energy-intensive industry will remain hard to electrify and will require other low-carbon alternatives.

Scale carbon-dioxide removal: It won’t be enough to reduce emissions and preserve today’s carbon sinks (although these remain vitally important goals); we will need carbon-dioxide removal on a large scale starting shortly after 2050.

Focus on forests, lands and food: Success requires that we do a much better job of protecting, managing, and restoring lands – both forested and agricultural – while at the same time addressing demand-side drivers such as food waste and global growth in beef consumption.

Explore strategies to tackle basic drivers: We need to further explore opportunities to influence powerful climate drivers outside of energy and land use, such as population increase and consumer behavior. This also means better connecting climate strategies with the other benefits they provide and with emerging trends such as automation and increasing income inequality.

General questions to spark conversation

- How can philanthropy best address the barriers to scale for carbon-dioxide removal solutions?

- Which engagements across agricultural and food systems make the most sense in a climate mitigation portfolio, both for mitigation potential and value in helping countries achieve and ratchet up Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

- How should climate philanthropy evaluate areas that are outside of energy and land use and determine if and how to engage? How can we better connect climate mitigation outcomes with the other benefits they provide?

These preliminary findings are a starting point for further exploration together. There are certainly more questions than answers at this point, reflecting the thorny nature of the challenge. This effort is meant to surface key questions about what an expanded planning horizon implies for climate philanthropy. We recognize the urgency to act boldly and collaboratively today to make 2050 pathways a reality.

The world requires nothing less than deep decarbonization of the transport sector by mid-century, yet only a few actors are needed to kick-start that transformation.

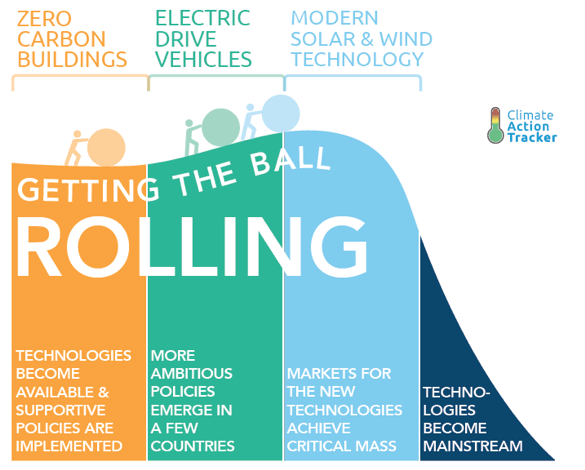

With our colleagues at the Climate Action Tracker, we took a close look in Faster and Cleaner 2 at the technological trends driving decarbonization in three sectors: power, transportation, and buildings. We found each of these sectors at different stages on the path toward deep decarbonization and mainstream adoption. Although much has been made of the remarkable growth in renewable energy deployment, the coming of age of clean electric-drive vehicles (EDVs) is only just beginning.

The barriers to enabling a clean mobility system at the scale and speed necessary for limiting climate impacts are significant. Today, fossil fuels still provide approximately 95 percent of transportation energy globally. Oil demand is rising in concert with economic development in many parts of the world, and the oil industry maintains significant political influence, especially in oil-producing countries. At the same time, transportation is now responsible for more emissions in the US and the EU than the power sector and is one of the fastest-growing sectors in India and China. Now, more than ever, it is critical that we address this question: what are we going to do about oil?

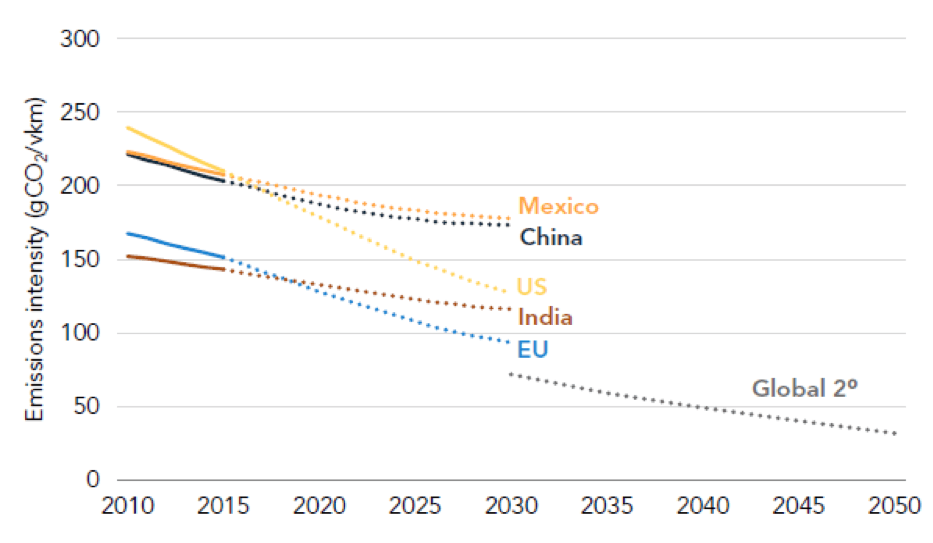

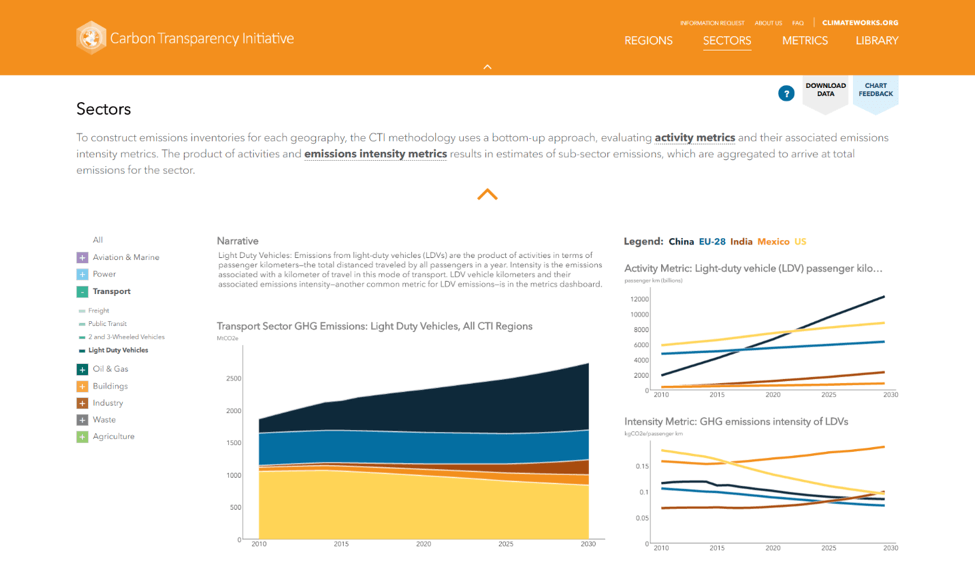

Fortunately, the decarbonization of the transport sector is underway. As ClimateWorks’ Carbon Transparency Initiative (CTI) modeling shows, the carbon intensity of road transportation has been declining due largely to increasingly stringent fuel economy standards for conventional internal-combustion-engine vehicles. Although the trend toward increasingly more efficient vehicles is encouraging, efficiency alone is insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals.

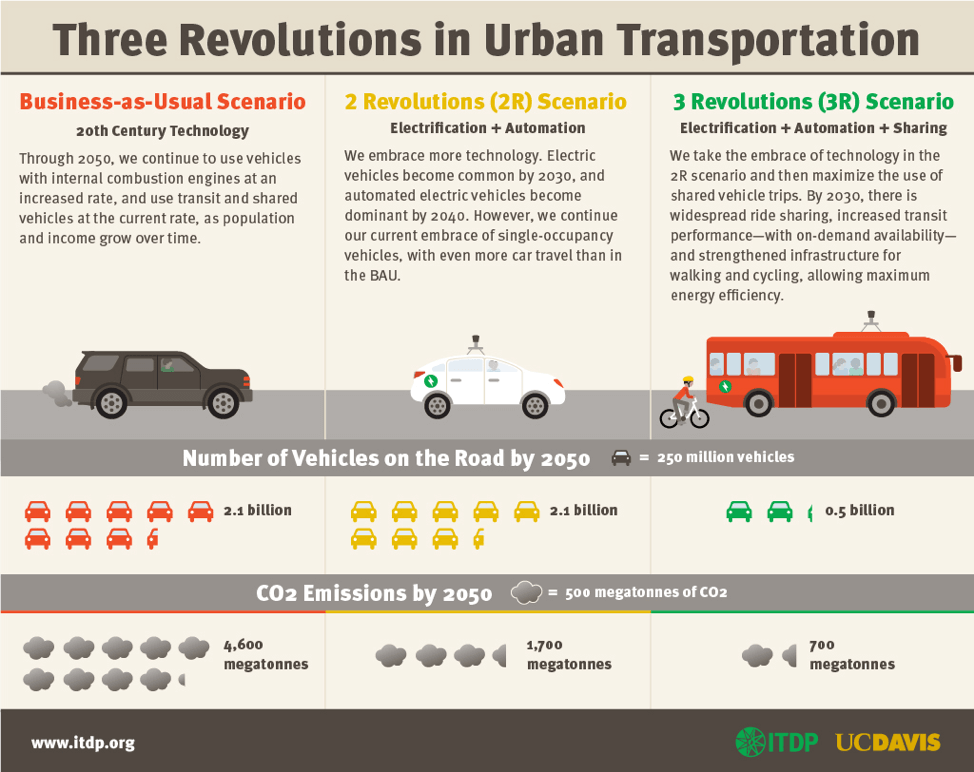

Due to leadership and supporting policies in key regions, the global market for EDVs is growing rapidly, outpacing many early projections. However, to achieve a future mobility system consistent with a safe climate, we need to grow the market even faster. In particular, we believe the confluence of three technology and market trends – increasingly affordable and long-range electric-drive vehicles, innovative new mobility services (ride share, bike share, dynamic and integrated transit), and high-level self-driving technology have the potential to radically redefine mobility and dramatically reduce oil consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. There are good reasons to believe these trends are mutually reinforcing: shared vehicles have high utilization, which accelerates fleet turnover and favors the relatively low EDV fuel, maintenance, and operating costs. Electric-drive vehicles use “drive by wire” systems that integrate well with autonomy and open the vehicle design envelope to increasingly efficient occupant design for sharing. Autonomy can further lower the cost of providing public and private shared-mobility services. Because EDVs can often be flexibly fueled, they can also facilitate renewable integration and improve use of utility assets.

Together, these three mobility “revolutions” could offer a host of benefits, including greatly reduced emissions that improve health and reduce risks of climate change, improved accessibility and reliability, increased affordability, improved safety, reduced congestion, avoided expenditure on road and parking infrastructure, and efficient land use in cities.

Several of the revolutions are already under way in select markets. China, Norway, the Netherlands, and California have enabled rapidly growing EDV markets that helped EDV sales reach nearly a million in 2016. Thirteen jurisdictions committed to “make all passenger vehicle sales in our jurisdictions ZEVs as fast as possible, and no later than 2050”. India has recently expressed its ambition to achieve a totally electric vehicle fleet by 2030; a recent report outlined strategies for the country to rapidly transition to relatively clean, low-carbon mobility solutions. To support this progress and expand beyond early adopters, we must replicate best-practice policies and strategies across key markets. Once we overcome key early-market barriers to low-carbon mobility solutions, those solutions will begin to outcompete oil-based transportation.

Philanthropy is uniquely positioned to help markets reach this tipping point at which reduced technology costs and profitable business models enable a scalable, affordable, accessible, and low-carbon mobility system. We can open the door for supportive policies by strengthening the voice of key constituencies (e.g., EDV producers and suppliers, safety and health advocates, mobility providers, and civil society) and broadening the base of support for a clean mobility transition. We can bring attention to address anticipated implications of new technologies, such as the economic and labor shifts implied by electrification and autonomy that, if properly attended, could turn potential opponents into strong allies. Once the door is open, we can support credible analysis, information, and technical assistance for policymakers and consumers. A clean mobility future is within our reach, but it is not inevitable. It requires champions willing to put resources and time into building the future we want. If we do it right, the prize is a system that provides affordable, equitable, and sustainable mobility for all.

A new report called ‘Faster and Cleaner 2: Kick-Starting Global Decarbonization’ from the Climate Action Tracker and the ClimateWorks Foundation shows how we have already seen dramatic, unpredicted progress on a number of fronts, and how we can build on that success.

The challenge facing countries and governments as they attempt to implement the commitments made to meet the greenhouse gas emissions goals enshrined in the Paris Agreement may seem daunting. But if you look closely, you’ll see that dramatic, unpredicted progress to decarbonize the global economy is already underway.

A new report called ‘Faster and Cleaner 2: Kick-Starting Global Decarbonization’ from the Climate Action Tracker and the ClimateWorks Foundation shows how we have already seen progress on a number of fronts, and how we can build on that success.

To be sure, we will have our work cut out for us. In order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement that would require the temperature increase this century to stay well below 2°C, we will need to completely eliminate net carbon dioxide emissions by 2050.

If it sounds challenging, it is. But ‘Faster and Cleaner 2’ looks at how we have succeeded in developing and scaling renewable energy systems, and describes how we are making big strides on transportation. The report concedes that much work remains to improve how buildings use energy, however.

The good news though is that relatively few countries and states can act to produce global benefits. This was made possible by informal coalitions that have transformed the internal markets of the participating countries and significantly influenced development outside of those markets.

The implications for philanthropy are profound. If we can build on that model by supporting ambitious policy development in even a limited number of countries or states, we can help new technologies to access the market, facilitate more investment in research and development, and use the benefits of scale to make them more competitive than old technologies.

We believe there is hope that this approach if applied broadly can push global emissions reductions on track towards zero emissions by 2050.

A Huge Win in the Power Sector

Over the last decade, the energy sector has seen a slight reduction in carbon emissions as the increase in renewable energy technologies consistently exceeded prior expectations. This decarbonization trend is likely to intensify in the future, as the economics of wind and solar drive further installations.

By 2030 renewable energy is projected to be the cheapest source of power in most countries. This progress was initially driven by a relatively small number of innovative countries with ambitious policy packages. We need to continue to learn from the experiences of these countries. In the near future, we would need a new coalition of countries to help advance policies to support the integration of high levels of renewable energy into a more flexible grid.

Driving New Technology in Transportation

Even though the carbon intensity of transportation has gone down in recent years, these improvements are not enough to meet the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals. We will need more than just increased fuel efficiency standards for conventional internal combustion engine vehicles. We will also need to rapidly expand zero-emission vehicles.

Demand for electric drive vehicles – including plug-in hybrids and battery-powered vehicles – has grown much faster than initially expected. As with renewable energy, a limited number of countries are taking the lead in the development of electric vehicle markets.

Ambitious policy packages in countries such as Norway and the Netherlands and states like California have created momentum that has led to these successes. And big countries are coming on board – later this year, China is expected to take the global lead in electric vehicle sales. India has just recently announced plans to become a 100 percent electric-vehicle nation by 2030. This is a critical moment, and coalitions of countries and regions need to initiate and continue to advance policies that can help the market rapidly switch over to clean transportation.

Tackling Slower Progress in Buildings

By contrast, there hasn’t been nearly enough progress in reducing carbon emissions by buildings. In the EU and the US, emissions intensity has shown a modestly declining trend over the past decades. To meet necessary targets, all new buildings in the OECD regions built after 2020 would have to be zero-carbon. It would also require an immediate expansion of deep renovation efforts.

Even though policies are in place in many countries around the world, decarbonization in the buildings sector is not showing an accelerating trend yet. In addition to the right sets of policies, the sector also requires a coalition of actors, including sub-nationals and businesses, to help drive the transition. Failure to do so would require additional emissions reductions in other sectors and would increase the need for even more advanced emissions technologies in the long term.

A Playbook for Success

Bold action by a few countries and states with strong, effective policies – supported by philanthropy – has made a huge difference in transforming markets in the renewable power and transport sectors to reduce our use of carbon. We will continue to need even bolder action, especially in the buildings sector, where technologies for zero-carbon buildings exist and where breakthrough coalitions could make a difference.

Fortunately, there is a playbook. ‘Faster and Cleaner 2’ shows how a few countries and regions supported new technologies and smart policies to transform markets. This report builds on analysis available as part of ClimateWorks’ Carbon Transparency Initiative, and is a timely reminder of what has worked well in the past and the value of tracking our progress. We hope that it will serve the climate community as an example of hope and opportunity as we continue to develop strategies to advance climate action.

On Monday, March 27, an exciting new philanthropic initiative made its debut.

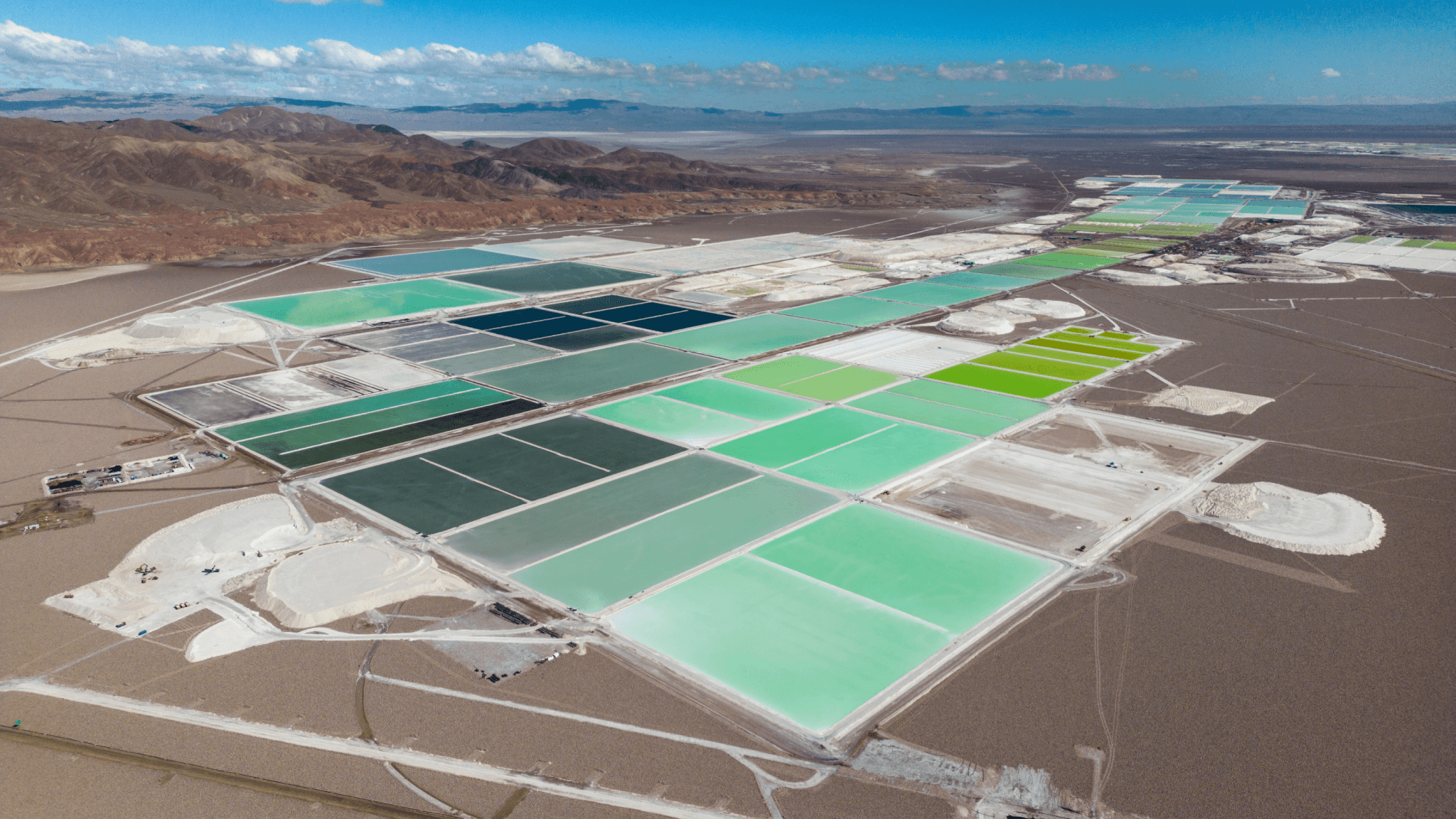

The Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (K-CEP) is a collaboration among 18 foundations that came together in September 2016 to announce a joint commitment of $52 million to help developing countries transition to energy efficient, climate-friendly, affordable cooling solutions. This is the largest single philanthropic commitment that has ever been made to advance energy efficiency in the developing world.

K-CEP was catalyzed by the Montreal Protocol, the famously successful 1987 international treaty that saved the ozone layer by phasing out global emissions of ozone-depleting substances, primarily chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Because CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances are also greenhouse gases, the Montreal Protocol resulted in massive additional benefits for the climate. By some estimates the Montreal Protocol has prevented the equivalent of 135 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from entering the atmosphere, making it the most significant greenhouse gas reduction program in history.

But in the years after the Montreal Protocol went into effect, a harmful side-effect became evident: manufacturers were replacing CFCs with hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), compounds that don’t damage the ozone layer but are, instead, greenhouse gases hundreds to thousands of times more potent than CO2. Over the last few decades, HFCs became very widely used in products like refrigerators, air conditioners, and insulation, and researchers began to predict that HFC emissions under a business-as-usual scenario could grow to the equivalent of one-fifth of global CO2 emissions by 2050. Recognizing this new challenge, climate advocates, governments, companies, and other stakeholders have been working for years to amend the Montreal Protocol to replace HFCs with alternative coolants that are kinder to the climate.

In October 2016, this sustained effort culminated in a landmark agreement at the 28th Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol in Kigali, Rwanda to amend the Protocol to phase down HFCs. The Kigali amendment prompted headlines around the world and inspired hope that the world is capable of controlling climate change.

In advance of the negotiations, the announcement of $52 million from philanthropic donors—plus a complementary $27 million from donor countries—to help developing nations transition to better cooling solutions, set a positive tone of ambition. Now that the agreement is in place, K-CEP will help the Kigali amendment succeed by making cooling more energy efficient. The Program’s goal is to “significantly increase and accelerate the climate and development benefits of the Montreal Protocol refrigerant transition by maximizing a simultaneous improvement in the energy efficiency of cooling.” Pursuing “simultaneous improvement” is smart. The Kigali amendment will necessarily drive changes in product designs, manufacturing, and markets as the sector transitions to low-global warming potential refrigerants. It makes good business sense to transition to more energy efficient equipment at the same time. Moreover, K-CEP will look beyond more efficient equipment to deliver low-cost cooling through building design, shade, fans, and other solutions.

The timing of this effort is crucial. Air conditioning is still relatively rare in many countries, but researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory project that the number of room air conditioners globally will nearly double from about 900 million in 2015 to 1.6 billion by 2030. We’ve seen fast market growth before: In urban China, use of air conditioners went from nearly zero in 1992 to about 100 percent in just 15 years. In the coming years, hundreds of millions of people in emerging markets will benefit when they purchase air conditioning for the first time. If the market moves to energy efficient cooling technologies that use climate-friendly refrigerants and other sustainable cooling solutions, the impact of this beneficial growth on global climate change will be greatly reduced.

The ClimateWorks Foundation is one of the 18 foundations that contributed to the $52 million commitment. We are also privileged to be the home of the K-CEP Efficiency Cooling Office. The Efficiency Cooling Office will essentially serve as the K-CEP program office, providing grant-making, reporting, program management, and other services to help K-CEP funders maximize the climate and development benefits of their commitments.

I am excited about K-CEP, and the ClimateWorks Foundation’s role in it, for three reasons:

1. Affordable, energy efficient cooling can dramatically improve people’s lives

Cooling protects public health and increases productivity, particularly in hot climates. Cooling is needed to keep vaccines and medicines stable, to preserve the nutritional value and taste of food, and to keep patients comfortable. Cooling is also needed to keep people safe during heatwaves, which regularly claim thousands of lives in both developed and developing countries. In this century of climate change, heatwaves will get worse and the health impacts will fall disproportionately on developing countries. For example, scientists project that heat waves will intensify across India in the coming decades, potentially leading to severe heat stress and increased mortality. In addition to public health hazards, a number of studies show that high temperatures reduce economic productivity.

2. The climate benefits of this transformation are huge

The transition to climate-friendly refrigerants combined with more energy efficient cooling can dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Scientists estimate that the Kigali amendment alone could avoid as much as 0.5° C of warming by 2100, giving a powerful boost to the international effort to keep global average temperature rise well below 2°C this century. And researchers estimate simultaneous improvements in energy efficiency could potentially double this benefit. ClimateWorks is funding new modeling to verify potential mitigation benefits, but there is no question the coming Kigali-driven transformation of cooling technology is one of the biggest climate solutions available.

3. K-CEP is an exciting model for philanthropic collaboration

The scale of this collaboration, the speed with which it came together, the potential for impact, and the intensity of ongoing funder cooperation as K-CEP moves into implementation are truly extraordinary. Many factors came together to make this work. A few pioneer foundations, including the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), Pisces Foundation, and ClimateWorks Foundation, invested over several years to help create the Kigali opportunity, and kept partner foundations apprised of progress. The excellence of the grantees who worked tirelessly toward an HFC amendment encouraged funders to engage. Philanthropic leaders like Hewlett Foundation President Larry Kramer and CIFF CEO Kate Hampton made a compelling case to other funders to seize the Kigali opportunity. K-CEP funders seized the moment and acted swiftly to make generous commitments, buoyed by the trust we’ve built together within the climate philanthropy community in recent years. Finally, a number of individuals across several institutions poured their time, expertise, and passion into creating K-CEP and the Efficiency Cooling Office.

Of course, K-CEP will only succeed if it actually reduces greenhouse gas emissions and improves people’s lives by helping them adopt affordable, energy efficient, climate-friendly cooling options, so it is critically important that we track results. K-CEP funders are developing a “Kigali Progress Tracker,” a shared results framework that will be used to track activities, outcomes, and impacts. A “scorecard” and regular reports will support real-time learning to share with the parties, institutions, and agencies of the Montreal Protocol and help K-CEP funders deploy funding as effectively as possible.

I’m confident that this bold, collaborative venture will significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve living conditions by helping people adopt affordable, energy efficient, climate-friendly cooling options. In many ways, projects like this are what philanthropy does best—apply “patient capital” to create opportunities and then move quickly to help leaders tip the scales toward transformational change, producing benefits people will feel for many years to come. This day was a long time in coming, but thanks to the work of a great network of funders and grantees, I’m very pleased to say that it’s finally here.

Today ClimateWorks Foundation released a set of tools that will help funders and decision makers within the climate community project and track progress toward a low-carbon economy by analyzing the drivers of emissions trends.

A while back, a colleague from a foundation committed to tackling the climate challenge mentioned that it would be great to have a crystal ball that would allow us to look into the future to see if the world is actually on track to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions.

What if we DID have a way to identify and track underlying drivers that could give us a better sense of how emissions were trending?

While the comment might have seemed like a flight of fancy at the time, it inspired some deep thinking at the ClimateWorks Foundation. The benefits of such information would be almost limitless – for funders, climate scientists, and policy makers.

The crystal ball would have to be pretty good to be useful, though. Tracking trends in greenhouse gas emissions is not just a function of underlying policies at the national or international level, but also of the pace of market investments and technological advances. And it would have to be dynamic, evolving as new technologies and policies come into use.

The staff of ClimateWorks love a challenge, and thus the Carbon Transparency Initiative was born. Today ClimateWorks released a set of tools that will help funders and decision makers within the climate community project and track progress toward a low-carbon economy by analyzing the drivers of emissions trends.

There are three main components of the Carbon Transparency Initiative:

The ClimateWorks Tracker

The ClimateWorks Tracker is a website that allows users to dynamically evaluate current progress in greenhouse gas emission trends at a glance. It displays data and trends for over 130 indicators that determine greenhouse gas emission pathways for many of the world’s economies.

The Carbon Transparency Initiative Models

The ClimateWorks Tracker draws upon the peer-reviewed Carbon Transparency Initiative Models to determine greenhouse gas emission pathways between 2010 and 2030, across all sectors of the economy for select geographies. The models are open and available to anyone. We can work with our partners to run custom scenarios and provide deeper analysis into any region or sector that the models cover.

ClimateWorks Advisory Services

The Tracker, Models, and other supporting data sets are part of the Global View Function at ClimateWorks. Our staff can provide the underlying analyses needed to help funders make investments to reduce emissions and to track the progress of those investments.

Better Information, Better Collaboration, for Better Philanthropy

We created the Carbon Transparency Initiative to help ClimateWorks Programs, funders, and other partners access reliable, consistent information to improve their strategies and track the progress of those strategies over time.

Better Information

The ClimateWorks Tracker presents data from our Current Development Scenario for China, the EU, India, Mexico, and the USA—which together represent more than half of annual global emissions. ClimateWorks is also developing a model for Brazil, which should be released in 2017.

The Current Development Scenario is based on current policies, decarbonization trends, and our evaluation of energy-related investments in eight sectors: power, oil and gas, transport, aviation and marine, buildings, industry, agriculture, and waste, with forestry under development. The scenario assumes that current climate and energy policies will remain in place and will be fully implemented.

We realized that we would need a robust set of data for the Tracker to be useful.

The ClimateWorks Tracker displays data and trends for over 130 fundamental indicators for decarbonization.

Here are just a few examples of the kinds of indicators that are included:

- Data on GHG emissions per capita

- The share of renewable energy generation in the power sector

- Electric Drive Vehicle (EDV) share of new vehicles

- GHG emissions of appliances per-household

Better Collaboration

The ClimateWorks Tracker provides the same data baseline across regions and sectors, and can be a useful tool for comparison and collaboration. It is hard to find such information consistently anywhere else. The tool can support funders who are interested in working together to ensure that sectoral or regional strategies complement each other. For example, someone interested in reducing emissions in the buildings sectors could compare data on space cooling (growing rapidly in countries like India), better codes and standards for new buildings in some of the fast developing countries, or on residential retrofit programs in countries like in the E.U. or the U.S.

Our tools can also support programmatic work in sectors and help regional policy experts who may want to compare the effects of certain policies on carbon emissions, such as understanding impacts from heavy duty fuel efficiency standards applied from the U.S. to other geographies.

The Carbon Transparency Initiative can also help reveal progress towards particular program or policy outcomes by assessing emissions reductions from changes in activity or carbon/energy intensity. To see how countries are able to meet their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions under the 2015 Paris Agreement, we also plan to use the Carbon Transparency Initiative tools to answer questions such as:

- Will India meet its renewable energy targets of 175 GW capacity in wind and solar by 2022?

- How might Mexico meet its stated Intended Nationally Determined Contribution of reducing overall emissions in 2030 by 22 per cent below reference?

- What are key additional policy interventions to reach beyond the current EU 2030 targets?

Over time, the tools of the Carbon Transparency Initiative will become even more powerful as we track actual progress of these drivers against projections.

Better Philanthropy

Through better information and better collaboration, the Carbon Transparency Initiative can help funders and decision makers understand the effectiveness of current strategies and help them refine those strategies over time.

While the ClimateWorks Tracker and Models are one of a set of tools that can be used to understand trends in greenhouse gas emissions, there are some things that the Carbon Transparency Initiative does not do as yet. For example, the landmark Paris Agreement could contribute significant reductions, but would require policies to be put into place some of which do not exist as yet, and thus are not yet part of the Current Development Scenario. Similarly, the expected reductions under the Clean Power Plan for the USA, which has not yet entered into force, are not included. As such policies come on-line, though, they will be.

In other words, the Carbon Transparency Initiative measures what is, not what could be. That said, the Carbon Transparency Initiative will continuously monitor how policies are implemented, incorporate that information, and track how the Current Development Scenario changes over time.

It is our hope that this is just a first step in providing more robust tools that will help philanthropy to make the most effective possible investments in tackling the climate crisis.

In order to do this, we are eager to hear from you about how the Carbon Transparency Initiative can advance your work as we annually update the data and assess trends. We hope that you will take a moment to explore the ClimateWorks Tracker at www.climateworkstracker.org and let us know what you think at cti@climateworks.org.

Without action, international aviation could make up over a fifth of global carbon emissions by 2050.

I love air travel. As the daughter of a pilot, I grew up recognizing different aircraft by their profile in the sky and could even identify specific helicopters based on their distinctive sounds. To this day, I still get a thrill every time a plane accelerates down the runway for takeoff.

But like it is for most people, flying is by far my largest carbon sin — accounting for 50-75 percent of my overall carbon emissions when my work travel is included.[footnote tooltip=”ClimateWorks Foundation is committed to being carbon-neutral. The organization offsets its greenhouse gas emissions from air travel and electricity use in its office with Verified Carbon Standard credits purchased through Terrapass.”][/footnote] Next week I will add to that carbon total when I travel to Montreal, Canada to attend the wrap-up of the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) 39th General Assembly.

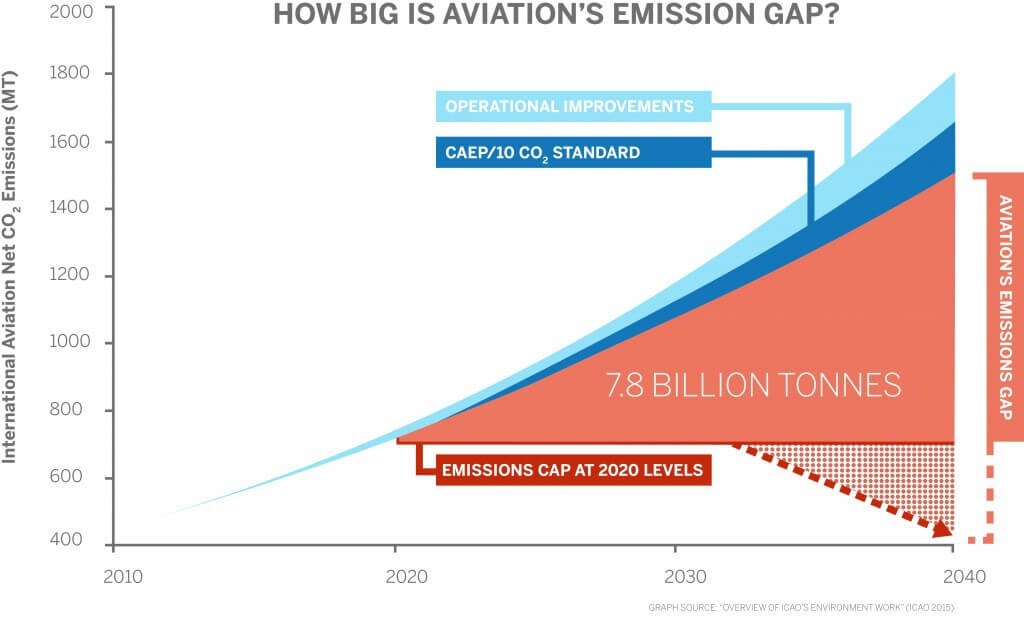

Over the next two weeks ICAO is expected to adopt a global market-based measure (GMBM) for international aviation, the world’s first global sector-wide cap on carbon dioxide emissions. ICAO has set a goal of carbon neutral growth from 2020 – i.e., capping net emissions at 2020 levels.

The General Assembly comes approximately 200 days after world leaders agreed to the landmark Paris Agreement and just one month prior to COP22 — when countries will discuss how to enforce the terms agreed to in Paris. With the General Assembly on aviation occurring only once every three years at ICAO, environmental observers predict that the Montreal outcome will be a key litmus test for countries’ willingness to deliver on the overall Paris Agreement.

The Magnitude of the Challenge

Global aviation is the seventh biggest global carbon emitter, producing more climate pollution than Canada or South Korea and just less than Germany – accounting for 5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, international aviation is growing quickly. If nothing is done to address the industry’s emissions, they are projected to balloon 300 percent above 2005 levels by mid-century and consume 22 percent of the world’s entire carbon budget to limit average global temperature increase to less than 2˚C by 2050. Put simply, the world cannot avoid dangerous climate change without addressing aviation emissions.

Beginning to Solve Aviation’s Climate Challenge with a Global Market-Based Measure

In 2010, the ICAO set a goal of carbon-neutral growth from 2020 levels (represented by the solid red line in the chart below). But given the sector’s projected expansion, the current CO2 standard and operational improvements (the blue wedges) are insufficient to deliver the reductions needed to eliminate aviation’s emissions gap. Furthermore, research suggests there is no realistic prospect of closing aviation’s 7.8 billion tonne emissions gap without a GMBM.

A GMBM would give each airline the flexibility to reduce emissions from its own operations and to purchase emissions units, including offsets, from other carbon market programs. Reducing emissions to meet the goal of the Paris Agreement (the dotted red wedge) will require additional reforms. Fortunately, a recent study by WWF and Stockholm Environmental Institute suggests that enough offsets that generate real emissions reductions and support sustainable development exist to satisfy the projected ICAO demand. Moreover, because ICAO adopted an unambitious CO2 standard for aircraft earlier this year, the GMBM if adopted will become the aviation sector’s main emissions reduction tool in the short term.

While some organizations are criticizing the not-yet finalized deal due to its reliance on offsetting, it’s important to understand that the agreement on the GMBM is just a first step. ICAO parties must move quickly to strengthen the ambition of the GMBM and to adopt measures that reduce, not just cap, aviation emissions. Additionally, important technical details, including those regarding emissions unit quality, accounting for full lifecycle emissions from biofuels, and ensuring no double-claiming of emission reductions, are all crucial aspects that must still be finalized to ensure environmental integrity.

Participation and Emissions Coverage

The current draft text that ICAO’s Assembly will consider marks a major shift from previous drafts. Instead of trying to identify a formula for defining which nations would participate in each of several phases, the new text proposes starting off with voluntary pilot phases.

The question of which states will agree to participate in the GMBM has long been a point of contention and many proposed formulas to determine inclusion have been sharply criticized due to limited emissions coverage. Recently a fragile consensus emerged among member states that participation in the first six years of the program should be “voluntary” – that is, rather than applying a single formula to determine who is covered and who is exempt, states should be invited to participate in the GMBM. While this proposed opt-in system would be a departure from ICAO’s stated goal of carbon-neutral growth after 2020 (CNG 2020), this “voluntary” approach enabled some developing countries to consider participation. While approval of the current draft resolution text is by no means assured, many states feel it strikes a delicate balance, and, to date, 63 countries, including the United States, China, and most European countries, have signaled their likely participation representing two gigatonnes of committed emission reductions from 2021-2035.[footnote tooltip=”Canada, Mexico, United States, Indonesia, China, 44 member states of the European Conference on Civil Aviation, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Singapore, Japan, Guatemala, Malaysia, Kenya, UAE, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea Australia, Thailand, Israel, Costa Rica and Papua New Guinea have so far pledged to join the GMBM. “][/footnote]

For the ICAO agreement to be effective, it is essential that there is maximum participation from states in the GMBM as early as possible.

Continued effort is needed to secure the commitments of aviation powerhouse states in the Middle East like Qatar; leading Latin American states like Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia; and leading African states including South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, and Senegal.

The next time I board a plane and reluctantly recalculate my carbon footprint, I will be headed to Montreal in support of the International Coalition for Sustainable Aviation, a group of NGOs that have been working for several years to secure an agreement on the GMBM at ICAO. With the Paris Agreement set to come into force by the end of 2016, attention is now turning to Montreal to secure an environmentally robust global agreement on aviation emissions, sending a critical signal to countries and industry alike that capping and reducing aviation emissions is essential to avoiding dangerous climate change.

The success of the Paris Agreement requires all countries to transform their climate commitments into real-world results. Accountability and transparency will be critical to the ultimate effectiveness of the deal 195 countries agreed to in December.

Under Article 13 of the Paris Agreement, nations will be subject to a common framework of transparency, and it is recognized that developing countries may need more help reaching their goals, measuring progress, and building on their national climate plans every five years.

To help countries in this effort, a new initiative was launched earlier this month by the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation; the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety; the Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea; and ClimateWorks Foundation. The Initiative for Climate Action Transparency (ICAT), will provide policymakers with the tools and support to measure, assess, and publicly report the impacts of their climate actions. Implementing partners of the initiative are UNEP DTU Partnership, Verified Carbon Standard, and World Resources Institute. The United Nations Office for Project Services manages the trust fund through which the work is funded.

ICAT will initially work in 20 developing countries to build capacity and foster greater transparency, effectiveness, and ambition of national climate policies.

ICAT will build a methodological framework for countries to measure greenhouse gas emissions and sustainable development impacts of their climate policies.

Additionally, expertise and capacity in developing countries will be supported through partnerships with governments, public agencies, and civil society organizations. The initiative is also creating a knowledge platform for countries to share experiences and lessons learned.

ClimateWorks is proud to support this collaboration, built in partnership with philanthropy, government, and civil-society. Our support for ICAT will also help analyze and integrate the commitments and actions of non-state actors — including businesses, states, regions, and cities — within the context of national and international climate action. Looking ahead, ICAT seeks additional financial resources from philanthropy and governments to expand and strengthen its geographical scope and methodological framework.

With the Paris Agreement in place, transparency and accountability systems that apply to all nations will help the world see how countries are following through on their commitments, and provide a mechanism for feedback so individual nations can understand the efficacy of their climate policies.

To learn more about the ICAT, visit www.climateactiontransparency.org or contact Surabi Menon.

ICAT implementing partners are seeking input to shape the project’s methodological framework and learn how the initiative can align with other efforts. To share your ideas, please participate in this survey by April 29.