Last year heralded several landmark developments in the electric transportation revolution, with significant growth across both the passenger and freight sectors. This is particularly timely, as road transportation continues to be a major source of global climate pollution which will continue to grow over the coming decades if we don’t change course – contributing to disastrous outcomes for our health, the economy, and the climate. Fortunately, due to the hard work of our partners, we are starting to turn the corner toward a cleaner transportation future.

Here, we unpack five encouraging signs of progress that we’re tracking at Drive Electric, the campaign to end the polluting tailpipe and accelerate the global transition to a clean transportation future. This progress comes from across geographies and vehicle segments, supported by the efforts of global partners, accelerated by collaboration, and fueled by philanthropy.

1. Electric vehicle sales skyrocketed, even during the pandemic

One key signal of progress on the road to zero-emission transportation is the increase in electric passenger vehicle sales, which are expected to have reached at least 7% globally in 2021, a 140% increase from 2019.

We track electric vehicle sales as a portion of all vehicle sales for two reasons.

First, achieving our clean transportation goals is less about the absolute growth of the market, and more about the accelerated transition away from polluting tailpipes toward cleaner, zero emissions transport powered increasingly by renewable energy.

Second, it shows us that transformative policies are working. Electric vehicle sales percentages are greatest in the regions with strong policy support like California, China, Norway, and Germany. For example, from 2019 to 2020, EV sales grew by 143% across Europe (with further growth in 2021), which analysts attribute to the strong European CO2 pollution standards. In the United States, the Advanced Clean Cars policy has been a key driver of the switch to electric vehicles. Originally pioneered in California, it has now been adopted by another 15 U.S. states (most recently Minnesota, and Nevada), accounting for over ⅓ of the U.S. market. Around the world and with public support, electric bus sales grew by roughly 22% since 2019 and are expected to have reached nearly 18% of all buses on the road by the end of 2021.

Drive Electric partners were crucial to this success, contributing to at least 30 significant policies throughout the world just in the first half of 2021.

2. Ambitious leaders are everywhere

It’s official, finally! 📣

— Monica Araya (@MonicaArayaTica) October 18, 2021

Chile 🇨🇱 is the first emerging market to end sales of petrol and diesel cars!

WELL DONE to the team at the Ministry of Energy and the e-mobility commission.

Who will be next? https://t.co/LYPma4QRYN @Drive_Electric_

In 2021, many countries, states, and cities increased their clean car ambition, while new players emerged as strong leaders in the global transition to electrified transportation. In the EU, an emergent frontrunner, nine member states requested that the European Commission support a date for the EU-wide phase-out of the sale of new petrol and diesel passenger cars and vans, and the European Commission is actively exploring a requirement for 100% zero-emission cars and vans across the EU by 2035 as part of it’s ‘Fit for 55’ package.

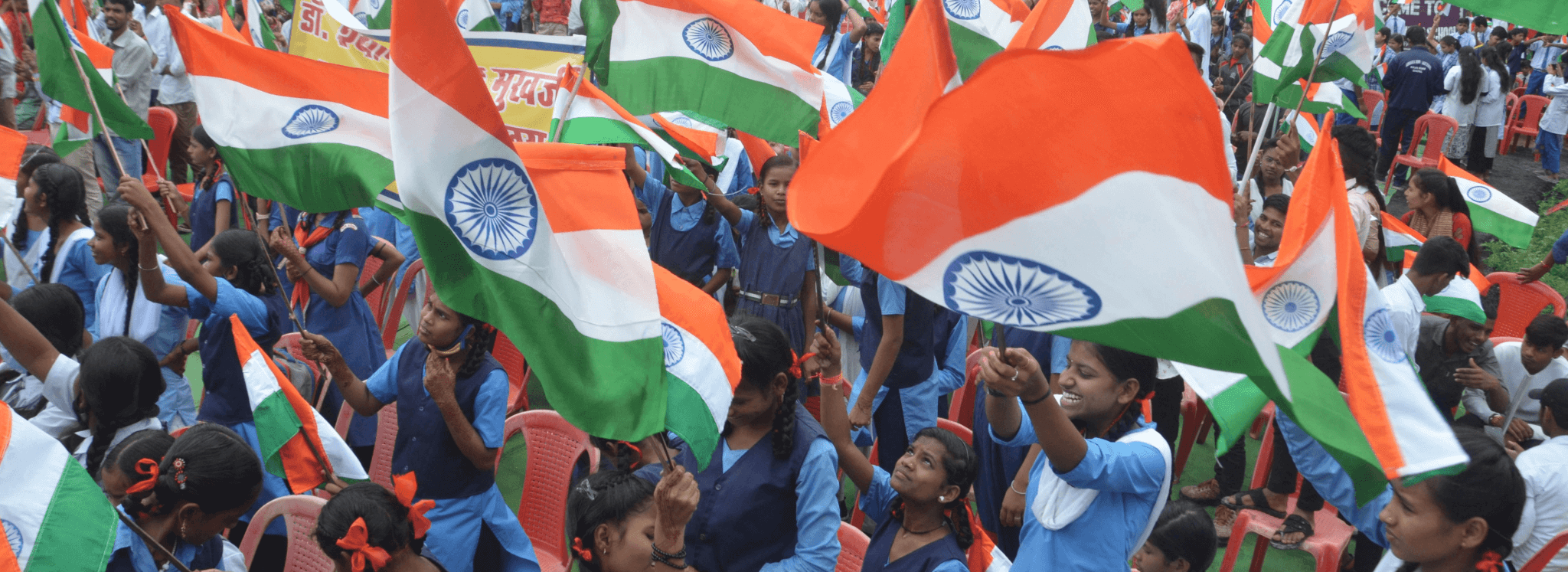

Several Indian states stepped up in 2021 by announcing impressive electric vehicle plans. The state of Gujarat launched its plan to support transport electrification while Maharashtra state came out with a strong electric vehicle policy of its own. This recent progress complements past EV policies in several other Indian states.

In the U.S., two executive orders by President Biden set an ambitious goal of making electric passenger vehicles half of all new sales nationally by 2030 and commit the federal government to fully electrified fleets, totaling 645,000 vehicles by 2035. These efforts send the political signal that the future is electric, and that rapid transformation is desirable and possible – in fiscal year 2019, just 1% of federal fleet vehicle purchases were electric.

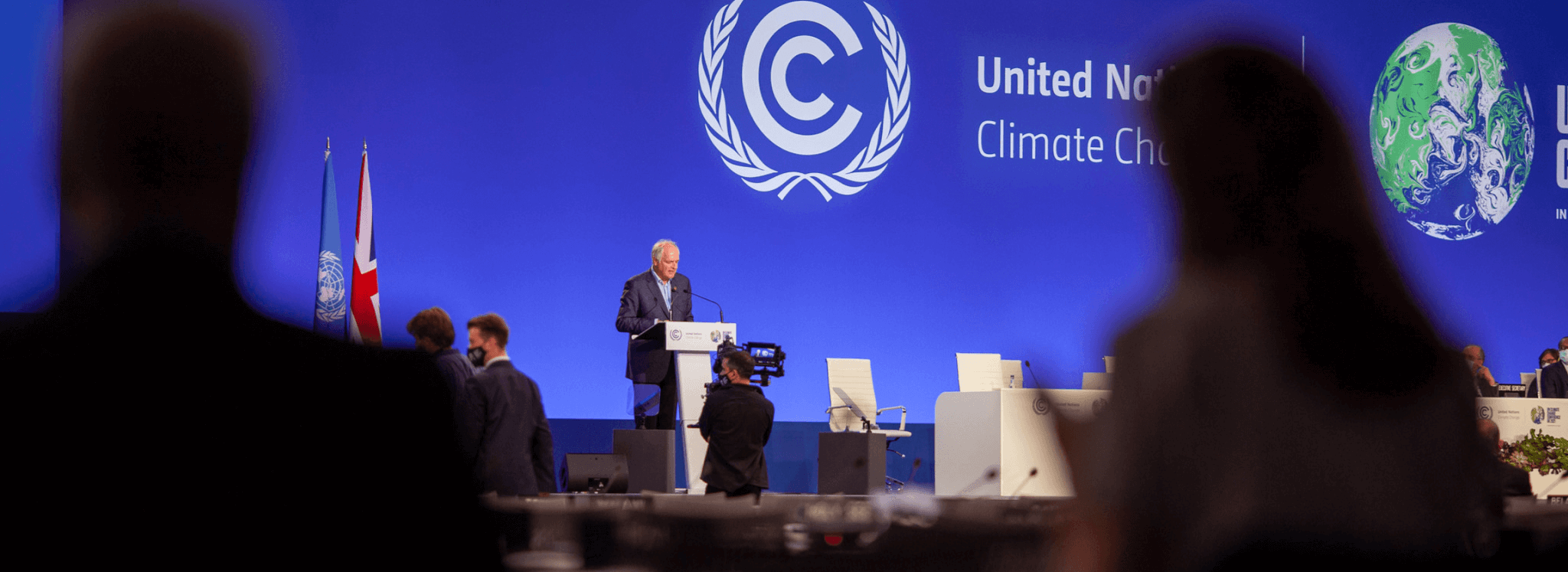

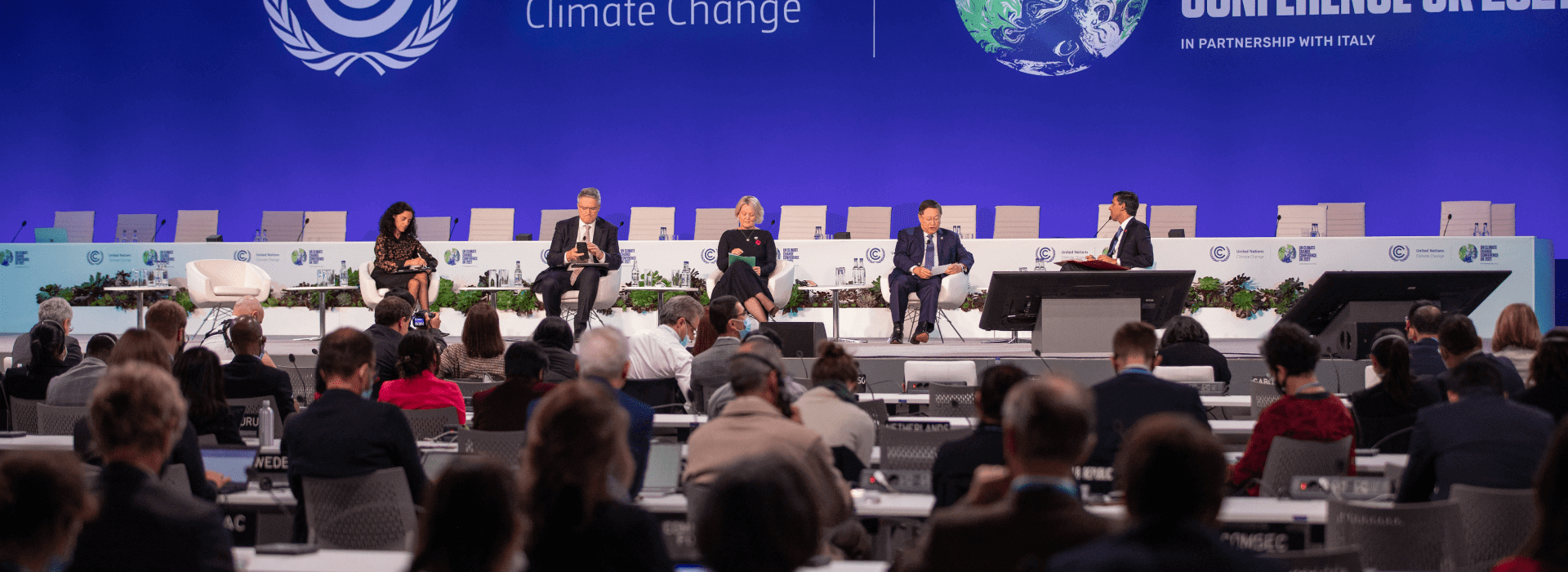

A major moment of 2021 was the signing of several big declarations and agreements at COP26 in Glasgow. This includes the “Glasgow Declaration on 100% zero emission cars and vans” signed by over 100 parties including nations, states, manufacturers, and other key stakeholders. Together, they agreed to support 100% sales of new cars and vans to be zero-emission by 2035 in leading markets, and by 2040 for the rest of the world. For a more complete wrap-up of COP26, check out our blog here.

3. Businesses are championing electric vehicles

Increased private sector interest in electric vehicles over the past year demonstrates the growing understanding that electric-drive transportation makes business sense. Whether it’s a fleet of electric buses that provide lower operating, fuel, and maintenance costs, or last mile electric delivery vehicles that showcase the industry’s positive actions in mitigating climate change.

To help businesses on the journey to tailpipe-free transport, Drive Electric partners like the Ceres Corporate Electric Vehicle Alliance (CEVA) and The Climate Group’s EV100 connect businesses to opportunities to lower their emissions, save money, and increase wider EV adoption. The participating companies account for a global fleet of well over 5 million vehicles, giving them market power collectively that no single company could attain. And they are increasingly adding their voice to policy efforts as well, bringing positive pressure on governments like calling on U.S. States to adopt the Advanced Clean Truck rule and calling on leaders globally at the UN COP26 to slash transportation pollution.

4. Clean freight is going global

Dramatically reducing emissions in the road freight sector is crucial to enabling commerce without damaging the climate or the health of communities living near ports, highways, and depots. The zero-emission technology we need is here today, and Drive Electric partners are working with manufacturers, suppliers, policymakers, and communities to accelerate uptake.

Building off momentum from the Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) rule adopted by California, communities across the U.S. are advocating for states to set standards that will shift trucking to zero emissions. Last fall, Oregon and Washington state adopted the ACT, making the West Coast a clean trucks corridor and this winter New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey followed suit. Together these states account for 20% of the nation’s fleet of freight trucks.

At COP26, zero-emission freight made headlines on transportation day with the new Global Memorandum of Understanding for Zero-Emission Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicles. Under the agreement, 15 governments agreed to work together toward 100% zero-emission new truck and bus sales by 2040. Check out Drive to Zero’s interactive dashboard to track and show policy development in leading regions, and a coordinated effort to engage subnational governments as well as top manufacturers and fleets in endorsing the agreement.

5. Cities are creating new visions for clean, healthy transport systems

Cities continue to be an important part of driving cleaner air and healthy transportation. Zero-emission areas are an exemplary policy that cities can adopt to transform polluted cities to sustainable and more livable places by restricting polluting vehicles, while expanding mobility access with e-bikes, electric buses, and charging infrastructure. In 2021, several countries set goals and targets for electrified cities, from the Netherlands to New Zealand. In Latin America, the ZEBRA bus initiative landed an additional $1 billion in investments to expand e-bus fleets across the region.

Transforming urban transportation is critical to meeting our global climate goals, according to a new report published by ITDP and UC Davis. The two members of the Drive Electric coalition emphasize the importance of pairing vehicle electrification coupled with policy changes that increase walking, cycling, and electric public transit.

Speeding the transition to save lives and secure a safe climate

Today, our roads continue to remain dominated by well over over one billion cars, trucks, vans, and buses powered by unsustainable fossil fuels and polluting engines that harm our climate and damage our health. Last year, our partners at the Clean Air Fund reported that poor air quality causes 7 million premature deaths per year, a significant portion of which comes from transport.

A better future is possible. The examples described here are just a few showing the collective power and efforts of Drive Electric partners in advancing smart government policies, engaging business leaders, and supporting people-powered coalitions to steer the future of zero emission transport.

Last year we saw policy proposals and commitments to electric transportation that were previously unimaginable – and still, this incredible progress means that about 23% of the world’s transportation is committed to zero emissions. All of the powerful momentum from 2021 demonstrates that now is the time for governments, companies, investors, and people around the world to take action toward meeting the ambitious Drive Electric Campaign targets of 100% transportation electrification before it’s too late – and for the sake of the climate, health, justice, and the economy.

In 2022, we look forward to building on this momentum. Drive Electric partners are already hard at work, expanding commitments and converting those into real-world policy and investment at the speed and scale needed. We look forward to working with all of you to make it happen.

On behalf of ClimateWorks Foundation Board of Directors, I am thrilled to announce that Helen Mountford will become the next President and CEO of ClimateWorks on January 24, 2022.

Currently serving as the World Resources Institute’s Vice President for Climate and Economics, Helen brings 25 years of international experience at the intersection of environmental action, economic development, and climate policy. She is a strategic thinker, global collaborator, and inclusive leader who is intentional about ensuring equitable and just solutions are at the heart of climate action.

In short, after a comprehensive, global search, we determined that Helen is perfectly positioned to build out ClimateWorks’ unique role and positive momentum to move even faster, deepen collaborations, and extend our global impact in the years ahead. Being able to build into the future with our next CEO from such a strong position is because of our terrific staff, steadfast philanthropic partners, and inspiring grantees.

We are excited for Helen to move into this role next month and will share more information in the coming weeks. Until then, warm holiday wishes and Happy New Year.

About ClimateWorks Foundation

ClimateWorks is a global platform for philanthropy to innovate and accelerate climate solutions that scale. We deliver global programs and services that equip philanthropy with the knowledge, networks, and solutions to drive climate progress. Since 2008, ClimateWorks has granted over $1.3 billion to more than 600 grantees in over 40 countries.

Increased engagement around the annual climate conference has created new opportunities and imperatives for philanthropy to be a delivery mechanism for commitments set forth there.

It has been several weeks since the conclusion of COP26 in Glasgow, and there are now many published analyses that evaluate the outcomes of the latest global climate summit. Some have been quick to declare failure, and while no one has declared a full success, many see real progress.

Objectively, the COP alone hasn’t put us on a pathway to 1.5° C of warming or provided the financial support needed to aid less developed and vulnerable countries in responding to the climate crisis. In the absence of groundbreaking new commitments among countries, some critics also argue that this was the 26th failed attempt at achieving a global agreement that gets the world on the path to a climate-safe future. However, these critiques are unfairly dismissive of the role of diplomacy in finding consensus among nearly 200 disparate parties on complex issues. While it highlights the immense work that is needed to get unambitious actors to join the cause, it doesn’t indict the entire COP process either.

All told, it’s hard to give a black-or-white assessment of whether this COP was a success or failure, but there were some developments at the most recent meetings that have important implications for climate funders.

The evolution of the COP process

Over the years, COP has begun to involve a gradually widening cast of characters. Since the Paris Agreement was signed at COP21 in 2015, the official negotiations among the 197 UNFCCC Parties have occupied a smaller space at the center of concentric circles of activities. Surrounding it are the non-state actors that are making an increasing number of commitments to reduce their climate impacts, and around them is the broader climate expert community, including organizations like ClimateWorks.

The reduced focus on official negotiations was on display in Glasgow, as the first week of meetings was dominated by thematic announcements, such as the Global Methane Pledge, among many others. This overall shift reflects a growing understanding that official negotiations can only take us so far in the limited time we have to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, and that addressing the climate issue in smaller, more manageable chunks can help to drive faster progress.

This development of parallel activities is noteworthy for climate philanthropy. In the past, COP had been a focal point for the small segment of funders focused on the official U.N. negotiation process, but the growing number of commitments being made by sector-based groups and other coalitions of countries means that the broader COP process is more relevant than ever for a wider segment of the climate philanthropy ecosystem.

Mounting public frustration

If the official U.N. negotiating process is at the center of COP’s concentric circles, the outermost ring comprises the general public, including marches and protests as well as other activities that are open to a general audience.

Paradoxically, even as the broader COP process is becoming more relevant to a wider range of actors because of the need to make progress outside of official negotiations, the official negotiating process itself is becoming more restrictive and exclusionary. For example, Climate Action Network, a ClimateWorks grantee representing 1,500 civil society organizations in 130 countries, had only two passes to enter negotiating rooms. This is significantly different from more expansive access NGOs have had in the past. Indigenous people, youth groups, and the disabled, among others, all complained of a lack of inclusion. Add to that the growing frustration that governments aren’t moving faster to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, and it’s no wonder that as 100,000 motivated people marched on the streets of Glasgow; they didn’t view the people in the conference center as allies.

This stark mismatch between public expectations for more high-level progress, the stodgy pace of the official negotiating process, and the complex patchwork of real-world advances in climate action, is problematic. Efforts like those of the two official COP Climate Champions have begun to address this imbalance, but climate funders have an opportunity and responsibility to use our relationships with a wide range of actors to explore whether these gaps reflect an inevitable difference in worldviews, a strategic balance of actors, or a need to refine structures and processes.

What’s next

As we’ve written before at ClimateWorks, the immense global challenge moving forward is the need to translate commitments made at COP into real-world actions and emissions reductions, and philanthropy has a clear role to play in catalyzing progress. We can ill afford to have the most motivated segments of the population view climate diplomacy as futile; their energy should remain an inspiration, not a force to be sidestepped. At the same time, much work needs to be done to better communicate to the public that encouraging progress is being made through other channels as well. Nevertheless, these many commitments will only be credible if they are implemented, monitored, and enforced.

There’s no shortage of opportunities emerging from COP. Several of our programs and initiatives — including Cooling, Finance, Forests & Land Use, and Road Transportation — have outlined some ways the field is poised for increased investment and accelerated impact. We will continue to share emergent opportunities ahead of COP27 in Egypt and as we enter the third year of this decisive decade to solve the climate crisis.

Cover photo: Jack Sauverin/UK Government

We will avoid the worst impacts of a warming world if we move at the pace and scale demanded by the enormity of the climate crisis and if solutions are lasting. Two critical building blocks for durable change are that, at a local level, people and communities most directly impacted have authority in decision-making, and at global scale, pledges of action are anchored in strong accountability practices.

An array of organizations and networks working for these climate solutions are poised for rapid growth, but investment to date has been scant, including from philanthropy. With its recent announcement of $443 million in new grants focused on these areas, the Bezos Earth Fund is meeting the moment by helping to close a critical funding gap and illuminate opportunities for others in philanthropy to support effective climate solutions.

The Earth Fund’s vital support to these historically underfunded areas will help boost efforts to protect the planet and people for generations to come. As part of these Earth Fund grants, ClimateWorks, a member foundation of the Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA), is excited to serve as the sponsor for support to The International Land and Forest Tenure Facility and Climate Action Tracker.

New support to secure Indigenous Peoples’ land and forest rights

The Earth Fund has granted a total of $30 million for The International Land and Forest Tenure Facility to advance Indigenous Peoples’ land tenure rights and the role of local communities and organizations in conservation in the Congo Basin (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo) and the Tropical Andes (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia).

The International Land and Forest Tenure Facility is the first financial mechanism to exclusively fund projects working toward securing land and forest rights for Indigenous Peoples and local communities while reducing conflict, driving development, improving global human rights, and mitigating the impacts of climate change. The Tenure Facility provides funding at scale directly to communities and their partners to build relationships with key actors within government and the private sector and provide the technical expertise required to implement tenure rights within existing laws and policy. In addition to the newly announced support from the Earth Fund, The Tenure Facility is supported by several donors, including the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Norad, and the Ford Foundation.

“Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ land rights are pivotal to biodiverse forest protection, strengthening direct local actors in equitable partnerships towards sustainable climate solutions,” said Nonette Royo, executive director of Tenure Facility.

“The Tenure Facility’s work to help secure community tenure rights in the Congo Basin and Tropical Andes and progress towards sustainable land use as part of the global response to climate change is critically important. We are excited to see the Earth Fund and ClimateWorks’ support for funding Indigenous and local communities securing tenure to their forests and lands.” — Nonette Royo, executive director of the Tenure Facility

Specifically, the Earth Fund grants will support Indigenous Peoples and local community groups to secure by 2026 the titles to 5 million hectares of land in the Andes and 1 million hectares of land in the Congo. The Tenure Facility will provide direct financial and technical support to organizations and networks on the ground, enabling them to build partnerships with champions in governments to advance the legal recognition of collective land rights.

Bolstering accountability and transparency in meeting global climate goals

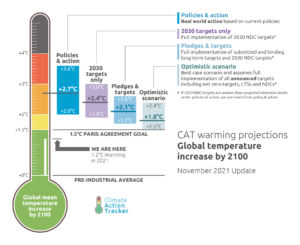

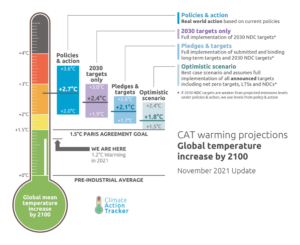

The Earth Fund has also granted $1.2 million to support the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent scientific analysis that tracks government climate action and measures it against the globally agreed-upon Paris Agreement aim of “holding warming well below 2°C, and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C.”

A collaboration of two organizations, Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute, the data gathered and disseminated through CAT is essential to tracking the necessary transformations required to meet climate and nature goals. One of its recent reports, for example, highlighted the credibility and action gap between nations’ ambitious 2030 commitments and policy implementation.

“Climate Action Tracker follows the progress of countries responsible for over 80% of global emissions to understand the effect of climate policies and action on emissions, and whether governments are doing their fair share to limit warming in accordance with the Paris Agreement goals,” said Surabi Menon, vice president, Global Intelligence at ClimateWorks. “As the pathways to limit warming to 1.5C narrow, it is important for policymakers and climate advocates alike to understand where emissions gaps exist and how policies and action can help close the gap. Climate Action Tracker is an invaluable resource, helping to increase transparency and accountability of governments worldwide.”

The Earth Fund grant will support CAT’s work to track progress toward transformations required in the energy sector, including identifying the indicators and datasets most appropriate for understanding advancements in energy, buildings, industry, and transport, as well as the establishment of new science-based benchmarks for these sectors. These data will be showcased on a data visualization platform, the Systems Change Lab. CAT will also contribute to knowledge products and narratives related to the state of climate action.

The Tenure Facility and Climate Action Tracker are examples of work that can be scaled to help keep the planet within a safe range of warming. We are proud to partner with the Earth Fund and support these organizations’ efforts to accelerate climate action worldwide.

Covid-19 has brought civil aviation to an inflection point. A precipitous drop in demand, continued reluctance of many leisure travelers to fly, and growing awareness among customers of the need to cut greenhouse gas emissions have all thrown a cloud over the future of passenger aviation. Meanwhile, new research reveals that aviation accounts for roughly 3.5% of human-driven climate impacts. These developments present enormous challenges and equally enormous opportunities for the industry to chart a path toward civil aviation achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Sustainable aviation fuels

One key component on that path is a dramatic increase in sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production and use. Fuels that have significantly reduced lifecycle emissions compared to traditional fossil fuels and comply with comprehensive environmental safeguards offer a way for the aviation industry to decarbonize rapidly and permanently.

SAF can be produced using a variety of renewable sources and waste feedstocks. To date, the uptake of sustainable fuels has been limited due to lack of supply and high production costs, but the capacity exists to ramp up production in the near-term. Because they burn more cleanly than fossil fuels, high-integrity SAF could also cut air pollution around airports, benefitting the health of people who live and work nearby. This may also help reduce the effects of non-CO2 emissions such as nitrogen oxides gases, water vapor, and soot, which all contribute to climate change.

A step in the right direction

The adoption in 2019 of the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) by the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) means that, at the international level, there is already a strong framework for sustainable fuels that became operational as of January 2021.

The recent decision by the ICAO Council to adopt the full list of SAF sustainability criteria further strengthens this framework. Agreement on sustainability criteria represents a major milestone for ICAO and the environmental community alike. The International Coalition for Sustainable Aviation (ICSA), a coalition of NGOs, played a leading role in delivering this outcome, but this outstanding achievement is still far from its final destination. The sustainable aviation fuels framework needs to continue to improve seamlessly, while resisting attempts by reluctant countries, airlines, and alternative fuel producers to water down environmental safeguards.

National actions complement global efforts

The CORSIA framework can enable the scale-up of sustainable fuels, if paired with effective national policies that generate the needed economic incentives. However, substantial work remains to improve many national policies to ensure that the incentives are directed to high-integrity SAF, rather than to lower-quality alternatives that make environmental problems worse.

In the interim, air carriers and large corporations committed to net-zero emissions can play a key role in pressing their peers to embark on the transition to net-zero flight, and by helping to shape strong national SAF policies. Most policies in this area are flawed in three key ways:

- They allow all biofuels to claim zero climate impact, even though some of these fuels are worse than fossil fuels, when accounting for both direct and indirect emissions.

- They allow fuels to be called “sustainable” even if their production hurts ecosystems and communities.

- And they allow “double counting,” when different parties can claim credit for a single set of emission reductions, undermining climate ambition.

The CORSIA framework for sustainable fuels corrects most but not all of these errors. Countries aiming to reduce the climate impact from aviation have an opportunity to build on the work done by ICAO to develop a framework for assessing emissions reductions from the use of SAF. By crafting robust national sustainable fuel policies, countries can channel investment toward high-integrity SAF and create a strong foundation for airlines, air carriers, and fuel producers to build on.

Philanthropy’s role

Philanthropy needs to play a key role in supporting NGO and civil society pressure on the aviation industry to decarbonize completely, keeping in mind that SAFs are just one near-term solution and that strategies focusing on demand reduction and carbon pricing will need to scale in tandem.

As it recovers from the impact of a global pandemic and plans for how to navigate a changing climate, the aviation sector has a blue-sky opportunity. This is a pivotal moment to jump-start the journey to net-zero aviation by further improving ICAO’s framework for sustainable fuels and shaping strategic national policies that support high-integrity SAF. If we successfully leverage these critical opportunities, we can put aviation on a new flightpath to reduce its climate impact and air pollution, protecting ecosystems and communities.

There have been many pledges and commitments on scores of issues at the 26th Conference of the Parties at Glasgow (COP26) these last weeks. Two sets of announcements – those on trade policy and on financial policy – may be particularly groundbreaking.

On trade, the US and EU agreed on greener production standards for steel and aluminum. The two countries may also raise border tariffs on imports whose production and consumption emit high levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution. At the same time, governments celebrated their commitment to the Paris Agreement by introducing regulatory reforms in their finance sectors.

For example, Central banks pledged to scrutinize firms for their climate-related financial risk. Market regulators like the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) indicated that companies seeking capital in their respective markets will likely soon be required to inform investors of their views about the low-carbon transition and plans to manage it.

These announcements were each powerful in their own right: here at ClimateWorks we’ve long worked on climate financial reform and clean buying standards. Together they also suggest that we are at the beginning of a new era in which the political path to a zero-carbon global economy will be faster, irreversible and more comprehensive. Why?

Because these commitments may break through the longstanding assumption that societies and governments are not responsible for their consumption-based climate emissions.

Pollution emitted from production and consumption

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, assigns responsibility to each country for the emissions produced from activities within their borders – production-based emissions. The Paris Agreement, collectively negotiated under the convention, calls for individual countries to gradually diminish their production emissions. The process has long assumed that decarbonization came at a considerable cost to the economy, and therefore each country would only seek to reduce their production-based emissions if others pledged to do the same.

Another assumption, perhaps even reinforced by the above framework, was that no society would want to take responsibility for GHGs created from the goods and services they consumed – consumption-based emissions – especially when produced in other countries. Such emissions would be other nations’ problems. Thus, consumption-based emissions have been left out of our treaties and conventions and less frequently discussed within civil society.

It turns out these assumptions weren’t quite right. Evidence shows that domestic interests drive decisions to decarbonize.

Under the right circumstances, constituencies can see decarbonization as in their own interest and actively pursue it. Domestic sectors may see the strategic advantages in transitioning to the low-carbon economy – emerging clean energy or electric vehicle industries, for example – and can propel shifts in the power and transportation sectors. Furthermore, societies-at-large may begin to prioritize decarbonization (climate change is, after all, an existential threat), individually and collectively taking responsibility for emissions both within and outside their own borders.

At least, in principle they could. But where is the evidence that they are?

Expressing domestic climate values globally

There are two ways in which an economy causes extraterritorial emissions: consuming goods and services that result in polluting activities abroad and investing and lending money that enables polluting activity abroad. The trade and financial policies now on the international climate agenda show that countries are beginning to the regulate GHG emissions produced by their consumption and financing.

By imposing tariffs on foreign goods and services with a higher GHG profile, countries are “pricing in” the cost of emissions – emissions represented in domestic consumption and production abroad. Trade policy experts have long derided most border tariffs as ineffective. They typically claim that such tariffs are intended to impose a penalty on foreign industries, but their actual cost is mostly borne by domestic consumers.

This is what critics ignore: by increasing prices on products, constituencies exercise their legitimate interest in reducing the climate impacts of goods manufactured abroad by pricing in carbon at the border.

Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) tariff provides an example where a confluence of civic attention to climate change and government appetite for scaled action have led to efforts that price in consumption-based emissions.

A cynic might assume CBAM is largely motivated by domestic protectionism. A less cynical view would hold the tariff as enabling domestic industries to decarbonize without having to compete with cheaper, polluting foreign substitutes. The fact that the EU had the political license to pursue CBAM at all may be evidence that Europeans are so concerned about climate change, they’ve chosen to take more responsibility for their consumption-based emissions. It is European consumers who would pay the direct economic costs of these emissions if the CBAM were imposed.

Financial policy also breaks down the border between domestic and extraterritorial emissions. A foreign company that seeks money in a domestic market would be subject to the same climate accountability rules as a domestic company, even if that company seeks capital for business abroad. Regulated financial firms are subject to financial supervision and regulation even when they are investing and lending abroad. And, of course, any investor – whether institutional or retail – that wishes to make their investments climate-aligned would need to address their international holdings.

Transforming the pace of decarbonization

Prioritizing consumption-based emissions alongside production-based emissions would mark a big change in climate policy, and thus pave the way for a more holistic and wide-reaching approach to emissions reduction. This could transform the pace of decarbonization for two reasons:

- First, the trade and finance policies discussed in this article may reflect states’ ability and willingness to introduce domestic policies that have global impacts. The fact pattern for CBAM reflects this potential: EU consumers were willing to bear what was effectively an EU-domestic tax on polluting US steel imports. This in turn resulted in the US raising its green standards.

- Similarly, a rule requiring climate disclosures from the US SEC would impact any foreign issuer seeking investment in the world’s deepest capital markets. Requiring domestic and foreign companies to disclose whether and how they are planning for the low-carbon transition allows investors to be informed consumers of public securities, aware of the climate related risks those companies carry wherever they operate.

In leveraging society’s climate consciousness and drive to find solutions, a nation’s trade and financial policy can have an amplified impact, as its effects ripple outward. This would be subtly seismic.

New emissions reduction commitments

The annual U.N. Conference of Parties (COP) meetings are a key global focal point for announcing climate-related pledges, commitments, and declarations. This year’s COP26, which just wrapped up in Glasgow, has proved no different.

For example, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised many by committing India to net-zero emissions by 2070, along with announcing a host of other targets for this decade, ranging from increasing renewable energy deployment to reducing the carbon-intensity of India’s economy (the amount of carbon emitted per unit of GDP). Many other countries communicated increased ambition through their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) toward achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, or provided their own net-zero emissions declarations. And the joint U.S.-China declaration reminded us that these two countries recognize the unavoidable importance of spurring each other to take action on climate, even during a period of heightened tension.

Actions weren’t limited to countries; corporations, sub-national jurisdictions, and other non-state actors also announced a host of science-based targets and sector-specific initiatives meant to drive down the greenhouse gas emissions responsible for climate change. Although there were notable areas with insufficient progress, such as on climate finance and the consideration of loss and damage claims, it was clear that overall ambition is on the rise.

How could new commitments impact the climate?

The potential impacts of the new commitments are entirely dependent on if and how they are implemented. Independent analyses by Climate Action Tracker (CAT) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) both found that full implementation of current pledges would most likely result in around 1.8° C of warming. While this would not meet the Paris Agreement’s most ambitious goal of limiting warming to 1.5° C, following through on these pledges would nevertheless be a massive improvement over our current path toward roughly 2.7° C of warming, which scientists agree would be disastrous.

Other analyses, such as an article from researchers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and other leading research institutions, focus on the near-term pledges embedded in the NDCs, and find that achieving those commitments would likely result in roughly 2° C of warming. According to their scenario analysis, if global ambition rises over time, the probability of staying below 2° C rises to 60%, but the chance of staying below 1.5°C is still only 11%. The problem is that we are quickly running out of time to scale ambition.

While these studies broadly agree on the impacts of implementing the pledges, the most important conclusion to draw from them is that there remains a large gap between the rhetorical ambition of these pledges and the implementation of credible policies and actions. Unless we can rapidly translate commitments into real-world emissions reductions, the pledges made at COP26 will end up as nothing more than lip service, as protesters on the streets of Glasgow have warned.

Opportunities for philanthropy

The latest round of ambitious long-term pledges should be a call to philanthropy to immediately begin developing and implementing the policies needed to achieve these targets. Philanthropy and its civil society partners have a critical role to play in kick-starting action today.

As a start, philanthropy should empower civil society to advocate for net-zero emissions targets that follow best practices outlined by CAT and are accompanied by policies that drive near-term actions. While commitments alone don’t achieve results, pledges do send important signals to other countries as well as to subnational and non-state actors. The global transition to a net-zero emissions world is a giant coordination game, and the evidence that higher ambition is becoming the norm will only spur further action and momentum.

Philanthropy and its civil society partners have a critical role to play in kick-starting action today.

A distinguishing feature of recent COPs is the growth of announcements and pledges by smaller coalitions of countries and non-state actors. There are so many multilateral commitments and announcements from these coalitions that this is turning into a parallel process to the official U.N. negotiations. Many of these independent pledges are quite ambitious and will both support the achievement of the official pledges and drive additional action in countries outside of the coalitions. It is here where the groundwork of grantees and philanthropic partners are bearing fruit with announcements in the areas of methane, road transport, shipping, finance, industry, carbon dioxide removal, forests and land use, and many others.

These pledges signal that some segments of the economy are ready for real, transformational change. They reflect back to governments a call for action and have the potential to smooth the passage of more ambitious policies, all the while signaling to investors that there is no shortage of new and growing opportunities, not to mention the transition risks associated with continuing with business as usual.

Conclusion

COP26 generated many new and ambitious climate pledges, and the latest analyses reveal that they could significantly improve our chances of limiting warming to 2° C or below. Whether we can achieve the potential benefits will come down to implementation. However, there is consensus that even these pledges are insufficient for limiting warming to the desired goal of 1.5° C, which would require action to be scaled up further and faster.

The pledges made at COP26 represent substantial improvement over previous commitments, and this is the first time they have been collectively assessed as sufficient to limit warming to 2° C. The increased ambition is heartening, but must be made a reality through implementation. Philanthropy has played an important role in helping drive this ambition, must keep pressing more ambition to reach 1.5° C, and must continue working to ensure that we realize the full potential of past, present, and future commitments.

____

Header image © HM Treasury

As part of Confluence’s series of climate-themed virtual convenings in and around COP26, I had the great pleasure to talk with Moutushi Sengupta of MacArthur Foundation, Uday Khemka of the SUN Group, and Pratap Raju of New Energy Nexus and Climate Collective Foundation on their strategies to address climate change in India and advance India’s climate ambition.[footnote tooltip=”Moutushi Sengupta oversees the MacArthur Foundation’s India Office, which provides grantmaking to civil society organizations to support initiatives that directly contribute to achieving India’s climate goals. Uday Khemka is a philanthropist, businessman, investor, and advocate for climate change mitigation and is Vice-Chairman of the SUN group. Pratap Raju is the founder of the Climate Collective Foundation and India country head for New Energy Nexus. Shilpa Patel is Director of Mission Investing at ClimateWorks Foundation.”][/footnote] Here are some highlights.

Context

India plays a critical role in the direction of our climate future. It is the third largest emitter in absolute terms, and although its emissions per capita are lower than the top two, it is the second most populous country in the world and poised to become the largest. It is also striving to lift its population into greater prosperity – so we can expect its energy use and therefore emissions to grow. The development path it follows will have a significant impact on climate. There is need for action across multiple fronts: policy, regulation, ecosystem development, investment – and across multiple sectors: energy, transport, agriculture, infrastructure. Our discussion focused on clean energy and the role for philanthropy and investment.

Different Approaches

The panelists put forth different approaches to promoting and supporting clean energy. The MacArthur Foundation has pursued an ecosystem-based approach to support climate action, advance climate-friendly policies and regulation, and build capacity. In impact investment, they provide a continuum of support, from pipeline development to direct investment to broader market development. Uday wears two hats: the first as a philanthropist who has worked on climate change mitigation since COP1 in Rio in 1992, accelerating his activities to look at Indian policymaking, climate finance, and climate philanthropy, and the second as a businessman who has established electric mobility and renewable energy businesses over the last decade in India and elsewhere. His focus is on scale and additionality. Pratap stressed the need for innovation: 30 to 40% of the technologies that we will need to steer us towards a net-zero world either do not yet exist or are not deployed on the ground. He sees a big role for startups and innovation, which his work supports in India. All agreed that these approaches are complementary and that there are many paths to progress.

Role of Philanthropy

Uday sees philanthropy playing a critical role in creating the bridge between government policy, the private sector, and civil society to create the policy environment within which new policies are formulated that attract capital and align markets. He mentioned the Clean Energy Finance Forum and the Rooftop Solar Policy Coalition as examples of such an approach. Philanthropic capital is the rarest form of capital, said Moutushi, and so we have to very carefully deploy it to the most catalytic uses, creating the conditions to mobilize large flows of capital, among others. Pratap focused on the startup ecosystem, which has grown by leaps and bounds in the last 15 years in India, and is today a vibrant marketplace with over 1200 startups in the cleantech space alone. But, there remains a significant gap between family or local support and private investors – and this is where philanthropic capital can build the platforms to connect startups to stakeholders.

Investment Opportunities

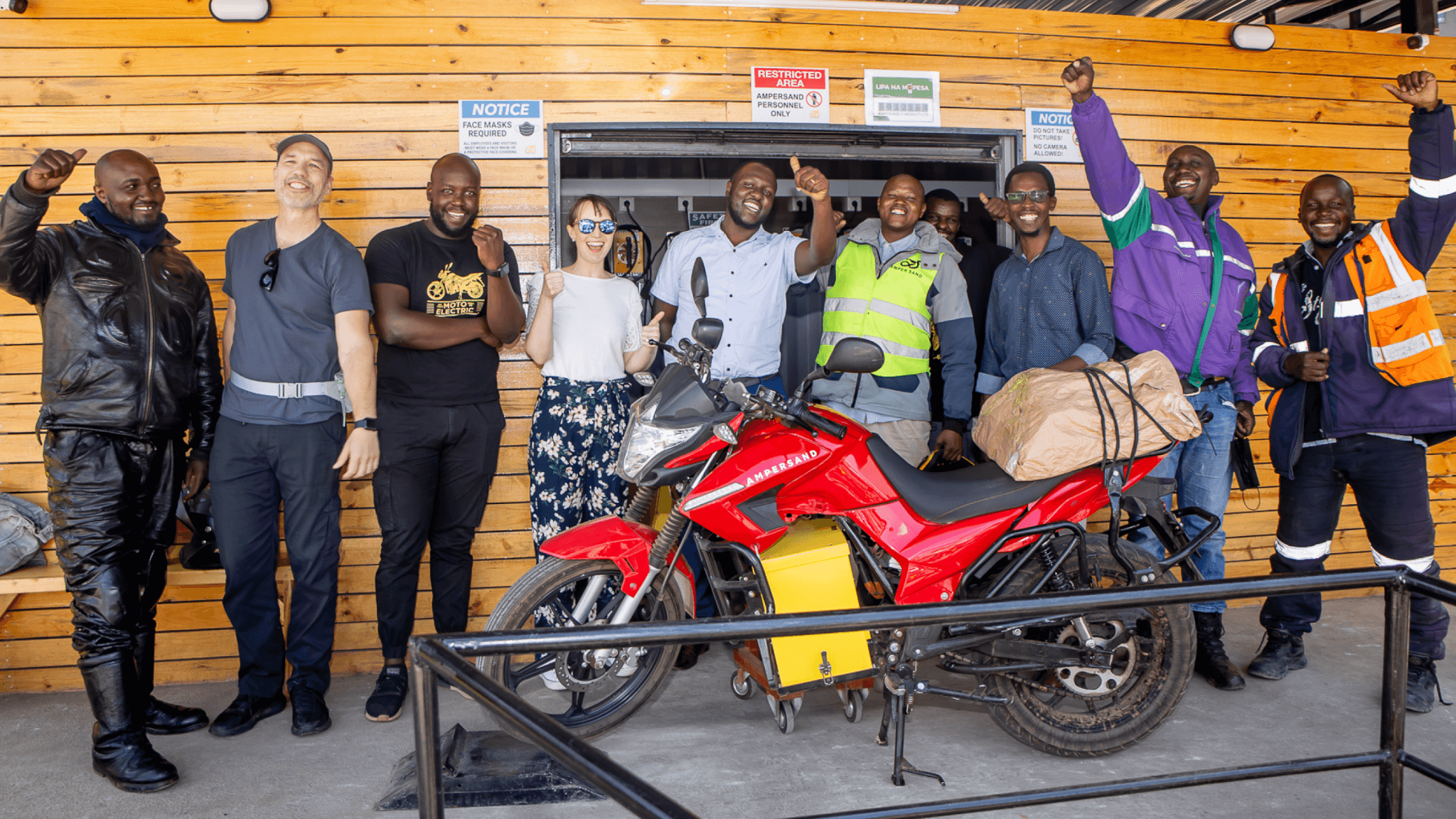

All three panelists saw significant investment opportunities in India. In the startup space, there is need for more impact capital over the next 5-8 years for early stage funding in pre-Series A and pre-seed rounds, until the ecosystem matures and stands on its own feet. In fact, Climate Collective Foundation is creating a “seed accelerator fund” to support the most promising startups that come through their accelerator each year. The Australian government is supporting the Climate Angels Network to crowd in more investors, both local and cross-border. Moutushi talked about the investment gaps that they identified in the rooftop solar space, and the resulting suite of interventions via the India Clean Energy Facility and the India Catalytic Solar Finance Program, financed by a consortium of foundations including MacArthur and ClimateWorks. These investments work through the Indian financial system and provide tangible evidence of results on the ground. Uday sees tremendous opportunity in India in clean energy and transportation and room for capital at all stages of enterprise development. His approach is entrepreneurial: creating network economics and network ecosystems that would be difficult to replicate and provide a competitive edge – as in the initiative that separates the battery from the vehicle and provides it on a pay-as-you-go model that makes EVs cost-competitive. He pointed out that technologies developed in emerging countries are sometimes better adapted to the developing world and have the potential to disrupt more developed markets.

Co-benefits and “Multi-solving”

A common thread that emerged is that these philanthropic approaches and investment strategies may have climate change mitigation and clean energy as their focus, but they generate ripple effects that deliver a lot more. Moutushi acknowledges that the journey towards clean energy may have disproportionate impacts on some groups, and it is important to MacArthur that these groups be supported in ways that allow them to participate in prosperity and the country’s new future. For Pratap, this means the inclusion of local entrepreneurs – including more women entrepreneurs – in the solution or deployment to increase the likelihood of success, and of using a “gender+climate” lens in startup business models and pitches to reflect the disproportionate impact of climate change on women. Uday says that we need to look at these issues holistically and stressed the co-benefits that clean energy can bring: the huge benefits to air quality in polluted cities and the economic empowerment that his battery-swapping initiative provides to low-income rickshaw drivers, for example.

The discussion was rich, in-depth, and nuanced. What is clear is that all the panelists are doing really interesting work and are very bullish on India. I am sure we will hear a lot more about them and their work as India implements its climate commitments.

Shilpa Patel is the director of mission investing at ClimateWorks Foundation. ClimateWorks is a global organization consisting of experts in climate science, public policy, economic and social analysis, and strategic philanthropy, and is committed to ending the climate crisis by amplifying the power of philanthropy. Shilpa works with partner foundations on the design and implementation of mission investing strategies and programs focused on climate change mitigation. Shilpa has been heavily involved in the India Catalytic Solar Finance Program, which is a multi-foundation effort aimed at developing the Indian rooftop solar market.

Listen to the recording here.

This post was originally published on Confluence Philanthropy’s blog here.

The Climate Imagination Fellowship is a project bringing together authors of speculative fiction to use the power of imagination to envision a positive climate future. Jason Anderson, program director at ClimateWorks, sat down with Vandana Singh, a Climate Imagination fellow, author, and professor of physics, to discuss how she integrates her interests in science and storytelling in conceptualizing the climate crisis. This interview has been edited for length.

The Climate Imagination Fellowship is a project bringing together authors of speculative fiction to use the power of imagination to envision a positive climate future. Jason Anderson, program director at ClimateWorks, sat down with Vandana Singh, a Climate Imagination fellow, author, and professor of physics, to discuss how she integrates her interests in science and storytelling in conceptualizing the climate crisis. This interview has been edited for length.

Jason: How did you first get interested in science and fiction?

Vandana: I was very lucky to grow up in India before there was a lot of globalization and technological distraction. Our playground was, in one sense, the cosmos. My brother and I would sleep under the stars and look up at the sky and wonder if aliens were looking back at us. I also read a lot, science fiction in particular. This led me to get really interested in science and it seemed almost inevitable that I would follow the path of science. One of the common aspects of science and science fiction is they both can evoke a sense of wonder.

Jason: Something that comes through in your writing is a real appreciation for the deep richness of storytelling. Is that something you grew up with too?

Vandana: One of the magical things about growing up in India is that you can almost pluck stories from the air. I was attuned to the notion of story from a very early age because we lived a very relational lifestyle. People were always in each other’s business, interacting in neighborhoods with deep relationships that extended beyond the family and so on, including non-humans. Even doing the simplest things, like going with my mother to the vegetable market in the evenings, people would exchange stories while buying produce.

Jason: Is your process of imagination different when you are conducting scientific work, and when you’re writing fiction?

Vandana: As a scientist, I have great respect for science as a rigorous process and the need to be very conscious of what influences, bias or preconceived notions you may bring to what you study. But in a sense, when we, as scientists, try to eavesdrop on what nature is telling us in these very different ways, one thing we may forget is that we are also a part of nature. Modern science requires this separation of the self from what you are studying. Science fiction allows me to get away from the subject-object separation that is the norm in science to be a participant observer in the universe.

Jason: Do you ever find yourself trying to predict things that might happen in the future?

Vandana: The question of predictability is interesting because the Newtonian, or mechanistic view, of the universe is what drives and animates most of modern science. This is where we think of the universe as a huge clockwork machine, even though relativity, quantum physics, and complex systems science tells us the universe is not Newtonian. The loss of Newtonian predictability doesn’t mean we don’t have any access to information about the future. But it demands different questions of us and gives rise to a more probabilistic sense of possible futures. The lack of certainty is exciting because there are so many “what if” stories you can write about possible futures.

We need to approach the climate crisis in an integrative way: carbon emissions and biodiversity loss, land system, other social, economic, and environmental problems.

Jason: We’ve been talking about physics but climate change is also very complicated. What is your opinion about how it is being approached?

Vandana: In my academic work, I try to re-conceptualize the climate problem through a trans-disciplinary, justice-centered perspective. It is science-based, but goes beyond the science to also consider the paradigms and perspectives we carry around with us, which are a consequence of our social, cultural histories, along with other influences. Most of the time we are not aware of our paradigms, a problem I call paradigm blindness. Once you are aware that your view of the world is just one conceptual construct, you can then say, “What are other ways to consider this issue?”

When I consider a problem like climate change that defies our current frameworks, I ask the problem itself to become the teacher. I must then develop a framework that is in response to the key characteristics of the problem, whatever they might be. And, I have listened to the stories of people on the margins, on the frontlines of climate change, to get out of my preconceived paradigms, to see it differently.

Unfortunately my sense of the mainstream climate discourse is that concepts and purported solutions continue to be grounded in the same paradigm that caused the problem in the first place.

Jason: When you’re contending with important current events like climate change, how do you balance the inclination to be didactic or campaigning with the need to write a compelling and creative story?

Vandana: It can be a hard balancing act sometimes, especially when it’s a problem you feel strongly about, as I do about climate change and I have a deep academic interest in it as well. I find that letting myself fall into the vortex of the story and letting it sweep me along allows the things that are important to me to surface in some form or the other without destroying the story.

Jason: In the short story “Indra’s Web,” in your book Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories, were you tackling the response to climate change more head on?

Vandana: Yes, I was. But while I did a lot of research on energy networks, and mycorrhizal networks, and thought about what a possible future city might look like – not a ‘smart city’ but a ‘wise city’ – it’s also a human story. I enjoyed writing it quite a bit!

Jason: Do you think about the kinds of technological transformations that are underpinning any discussion of positive climate futures? Do you think we need to drive the same kind of transition in the accompanying social order, and is that even possible?

Vandana: Both need to happen together. We are used to looking at technology as though it existed independent of the social, ecological, and economic context. If we are simply thinking of substituting fossil fuel technologies with renewables, then we are making a major mistake. The climate problem is not solely a scientific-technological one; it is also about our socio-economic system and our paradigms. We need to approach the climate crisis in an integrative way: carbon emissions and biodiversity loss, land system, other social, economic, and environmental problems.

Jason: Are you essentially saying to solve this big problem, first we need to solve this even bigger problem?

Vandana: It’s not a question of solving one problem and then solving the other. The socio-economic-cultural paradigm of modernity tends to encourage sequential, compartmentalized thinking. The fact is, the climate problem is related to all these other major social-environmental problems, and therefore the solutions need to emerge from a paradigm that recognizes their inter-relatedness. Such solutions would tackle our entangled problems together, in an integrated way.

We live in a complex world and we have interacting complex systems. The future isn’t totally determined. Is it possible to find some kind of response that can marry a few rivulets together so you have a stream that can turn the river away from the edge of the cliff?

Jason: You often bridge past and future within the same story and refer to time as a river delta with rivulets that split off and recombine. Is there relevance to climate change in this perception of time?

Vandana: Time has always been a fascination for me. I think the way time can be like a river delta instead of simply an infinitesimally thin axis going off into the future is precisely because of the fact that we live in a complex world and we have interacting complex systems. The future isn’t totally determined. Is it possible to find some kind of response that can marry a few rivulets together so you have a stream that can turn the river away from the edge of the cliff? Story allows you to experiment with all those possibilities.

Jason: What are your thoughts on optimism and what form that can take in a world where you have deep inequality, a history of colonialism, and a pretty bad track record of actually dealing with climate change?

Vandana: There are people who are optimistic because they have privilege. But we know that the world is full of suffering. It is very important to acknowledge the power structures that cause this, and that power itself is part of the problem because it stands in the way of needed change. The kind of optimism that appeals to me is not the empty or delusional optimism of the privileged, but the defiant, creative persistence of the marginalized, despite great odds.

And it’s not just human suffering, but multi-species suffering.

I also feel that hope and despair are both traps. Maybe what we need to do is focus more on meaning. When people work together, we can grieve together, we can weep together and celebrate together. It’s not only about doom and gloom.

Jason: What have you picked up from mentors in your own path that you’d like to pass on to younger people?

Vandana: That there is beauty and creativity and intelligence in the right kind of togetherness. That we need not be alone. That the world is not a machine. That we are a part of something incredible – the web of life on our planet. That it’s all right to howl at the moon when the moment takes you. That change happens sometimes when we least expect it.