Maritime shipping lies at the heart of global economic activity. Ships transport about 90% of all international trade, including consumer, industrial, and agricultural commodities. However, the sector is also responsible for 3% of all global greenhouse gas emissions, and ship pollution leads to at least 60,000 deaths a year, with a disproportionate impact on port communities. Addressing this challenge is crucial to combating the climate crisis and protecting public health.

In July, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the sole regulator for maritime shipping, announced a strategy revision for the industry that aims to achieve emissions reductions of 30% by 2030 and 80% by 2040, signaling the beginning of a rapid transition to net-zero emissions. While many experts agree that the IMO’s recent strategy revision is not fully aligned with Paris Agreement goals, the shipping sector can still achieve a 1.5° C trajectory, reducing global shipping emissions and protecting the health of port communities.

ClimateWorks Foundation partners with local communities, public and private sectors to transform the maritime shipping sector toward a carbon-free future. We partner with non-profits that work to eliminate ship pollution — such as the United Nations Foundation and Opportunity Green to decarbonize maritime shipping by 2050. I spoke with Aoife O’Leary, founder & CEO of Opportunity Green, and Susan Ruffo, senior advisor for ocean and climate at United Nations Foundation, on how the shipping sector can achieve zero emissions by 2050.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What makes shipping so important for global efforts to combat the climate crisis?

Aoife O’Leary: Shipping is responsible for 3% of global emissions. This might seem relatively small, but if the shipping industry were its own country, it would rank as the world’s seventh-largest emitter, comparable with countries like Germany and South Korea. Addressing the climate crisis requires us to tackle the emissions from the shipping sector. Shipping is integral to global trade and has historically contributed to economic growth worldwide. Given its impact on various economies (particularly emerging ones), shipping must take center stage in a just and equitable transition. This will involve implementing green solutions not only in high-income countries but also in emerging economies.

Susan Ruffo: We need to debunk the myth that shipping is an extremely difficult sector to decarbonize — and to clarify that we already possess both the knowledge and the growing momentum to overcome the challenge. Some other sectors like agriculture are complex due to their multitude of individual actors and lack of a standardized authority. In contrast, for the shipping sector, there exists an international regulatory body with the power to set and enforce rules, and there are relevant technologies available. Decarbonizing the supply chains that encompass most of our daily goods and food hinges on addressing shipping emissions. Neglecting this issue could exacerbate the problem, especially as shipping continues to expand. In the fight against climate change, focusing on shipping is pivotal.

Given shipping’s importance to economies, why are we emphasizing decarbonization with such urgency?

O’Leary: It’s important to clarify that the effort to decarbonize shipping isn’t an attack on its role in economies. Rather, the objective is to collaborate with the shipping industry, governments, and supply chains to navigate the transition toward decarbonization. While shipping has contributed to economic growth, the landscape is changing. Governments are increasingly recognizing the potential economic opportunities linked to adopting sustainable practices and recognizing that the shipping industry pays little in the way of tax. This transition isn’t solely about increasing costs; it’s about fostering sustainable development by investing in renewable energy and green technologies. It’s essential to strike a balance between economic growth and environmental responsibility, especially if we are to ensure the continued sustainable development of the countries most impacted by climate change.

Ruffo: Many governments are now embracing the transition due to its economic potential, rather than just the notion of increased costs. This is particularly true for countries with the capacity to produce renewable energy and green fuels. For them, this transition presents an opportunity to stimulate new forms of economic growth. With the IMO’s new targets, we can expect movement toward new zero-emissions fuels. This will increase shipping costs in at least the short run, but if it is coupled with the kind of emissions pricing regulations the IMO is now discussing, there is an opportunity to direct investments into the sector. The key question centers around executing this transition in a controlled and planned manner that alleviates the burdens on the most impacted countries.

The IMO’s refreshed strategy has received criticism for its non-binding targets and for not being aligned with 1.5° C targets. What is the context behind this criticism?

O’Leary: The IMO’s strategy isn’t currently binding, and it lacks specific measures to achieve its stated targets. Nevertheless, it represents significant progress from previous positions. However, the absence of alignment with the 1.5° C target is a major shortfall. This is especially concerning as temperatures in July of this year already matched the 1.5° C warming benchmark. Despite its imperfections, the strategy instills hope and offers a foundation for further development. The unanimous adoption of the strategy sends a strong political signal, providing clear direction to industry stakeholders. Although there are gaps, the strategy holds potential, and it’s a starting point for progress.

Ruffo: It’s disappointing that the strategy doesn’t fully align with the 1.5° C target, which is a letdown for parties such as the Pacific Islands countries, the United States, and the United Kingdom that pushed for higher ambition. However, their efforts definitely drove the strategy’s current level of ambition, which is a big step forward. The unanimous adoption of the strategy is politically significant and provides the industry with a much-needed signal to press forward. We should also remember that the strategy itself was never meant to be binding — it is meant to set the bar for the sector. Now the IMO will develop implementing regulations that will get us to that bar. It is important to note that, unlike the Paris Agreement, the IMO has the capacity to implement enforceable rules. These rules can help substantially reduce emissions if they are correctly aligned with the strategy’s high ambitions.

How did political dynamics influence the IMO strategy? Were there any unexpected country positions?

O’Leary: While major blocs like the Pacific Island countries have gained influence, a significant number of ambitious climate impacted countries still aren’t present due to the IMO negotiations to capacity constraints. Having these countries in the room could reshape the dynamics of the discussion, as many of them hold climate ambitions. A substantial surprise lies in the European Union’s positions. Despite enacting various shipping legislations, the IMO’s strategy outpaces the European Union’s ambitions in certain aspects. This raises intriguing questions about how these divergent approaches will unfold. Fuel standard measures and pollution levies are of high interest to many countries because they can generate climate finance for adaptation and mitigation in countries most impacted by climate change. However, those countries aren’t necessarily in the room to help make those decisions.

Ruffo: Given their historical climate ambition at the IMO, the Pacific Island countries’ forward-thinking position on shipping is not surprising — but their increasing influence is noteworthy. It’s crucial that high-income countries like the United States and the United Kingdom support them in maintaining high expectations. Ultimately, it was the Pacific Islands countries, along with newer participants aligned with them, that pushed the strategy’s ambition forward. Additionally, the strategy’s implications extend beyond IMO, notably in setting a precedent for a globally enforceable carbon pricing mechanism. This is critical for driving emissions reductions.

What are the implications of the IMO’s revised strategy on national action plans?

Ruffo: The IMO strategy has resulted in a clearer industry signal that can influence decisions and investments. Countries, however, haven’t immediately shown plans to act solely based on the strategy. The focus appears to be on aligning existing regulations — such as the EU Emissions Trading System — with the IMO’s strategy. On the industry side, clearer messages have emerged, indicating that regulations will impact currently purchased ships, thus prompting shifts in investment perspectives. National action can include investing in ports, infrastructure, and clean energy and fuel production — and hopefully, the IMO’s decisions will catalyze these efforts.

O’Leary: The IMO strategy has undeniably conveyed a more definitive signal to the industry. Curiously, the industry seems more preoccupied with the 2050 net-zero goal and its proximity to 2040, rather than the nearer 2030 target. This might reflect industry perceptions of whether measures will be in place by 2030. Importantly, the strategy dismisses the shift to liquefied natural gas (LNG) as a climate solution. It highlights that all greenhouse gasses and the full lifecycle of fuels must be considered — which should sideline LNG due to its lifecycle methane emissions. While the strategy doesn’t currently outline steps to achieve zero emissions, we anticipate that upcoming measures could address this gap. The specific nature of the fuel standard remains to be seen, though we already know what technologies we need to decarbonize the industry.

Where can philanthropy fill the gap in scaling up investments toward green shipping?

O’Leary: Philanthropy’s contributions have been substantial in supporting organizations and networks pivotal in shaping the strategy. However, significant work remains to be done. The need for first movers in voluntary actions is essential. While some industry leaders have shown a willingness, there is a need for legislative support. Philanthropy’s value lies in offering a higher-level strategic perspective, identifying gaps, and aiding in their resolution. A core focus is on representation in decision-making processes. Nonprofits play a critical role here, though the ultimate responsibility rests with governments.

Ruffo: Philanthropy’s unique advantage is its ability to embrace risk without immediate monetary returns. This flexibility, coupled with a higher risk tolerance compared to traditional capital sources, can propel philanthropy to play a pivotal role in decarbonizing the sector. It is vital to provide support in areas such as bolstering countries’ presence in meetings and fostering cross-sectoral connections to climate ambition — even if these actions don’t readily yield monetary gains. This important role seems to be uniquely filled by philanthropy. Organizations like ClimateWorks Foundation — which are involved in promoting green shipping but also broader climate and renewable energy development efforts — remain key in bridging gaps that may arise due to fragmented institutions at the national level.

Next week, heads of state and climate leaders from around the world will convene at the inaugural Africa Climate Summit in Nairobi, Kenya. Co-hosted by the African Union Commission and the Republic of Kenya, the event will focus on collaborative efforts to drive green growth, climate finance, and solutions for Africa and the world. The gathering is being held during Africa Climate Week, which is hosted by the UNFCCC and the Kenyan Government. It comes at a crucial moment amid a global push for greater and more effective climate finance, especially for the countries least responsible for and disproportionately impacted by climate change.

As a continent that has long been at the forefront of climate change, Africa is pivotal in the global fight for a livable future. Africa is uniquely positioned to draw on its expertise, share insights, and advance solutions that accelerate green growth and support global renewable energy needs. The Africa Climate Summit is a can’t-miss opportunity for governments, philanthropy, and organizations both inside and outside Africa to collaborate and advance collective climate action.

A landmark summit

We are approaching an important point in this year’s climate calendar. Earlier this year, the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact generated momentum but not much action for reimagining the international financial system to address inequality and climate change. Since then, global climate impacts have only intensified, and the pressure is on for leaders to translate good intentions into tangible outcomes.

The Africa Climate Summit is well-positioned to help accelerate climate action. With big deals for private and public funding anticipated next week, there are positive signs that the summit will deliver critical investments for nature-based solutions, clean energy, and climate adaptation. This progress, in turn, will help spur more transformative action at COP28.

The summit also marks a milestone for the African region and its role as a global climate leader. The event seeks to promote collaboration and collective action and “shift the narrative away from a division between the Global North and the Global South in addressing the climate crisis.” At the same time, there are growing concerns about non-African influences on the summit’s agenda overshadowing regional priorities.

We believe the summit will be a watershed moment for global climate cooperation because it is the first time that leaders from Africa have organized a special global climate summit to accelerate climate action. The themes are particularly relevant to countries in the Global South, including financing climate action and green growth. In particular, with just energy transitions and partnerships (JETPs) gaining traction in Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam) and Africa (South Africa and anticipated in Nigeria and Senegal), the summit is an opportunity to not only highlight specialized climate financing, but to also ask questions about its structure, efficacy, equitability, and implementation.

A growing opportunity for philanthropy

Since 2015, climate philanthropy funding to the African continent has been rising by an average of 30% each year. Between 2020 and 2021 alone, funding grew rapidly with a 50% increase. Despite this progress, funding falls far short of the need, and the region accounts for only 5% of total funding for climate mitigation action. More broadly, total annual climate finance flows in Africa stand at only $29.5 billion — significantly less than the $277 billion per year that African countries need to implement their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and meet 2030 climate goals, according to a 2022 report by the Climate Policy Initiative.

A growing number of local partners, including the African Climate Foundation, are guiding funders as they increase their engagement in Africa. At ClimateWorks, we have expanded our activities with more funding to implementing partners based in Africa and international partnerships designed to support the region’s push for sustainable climate finance and clean energy while ensuring a just and equitable transition.

For the Africa Climate Summit, ClimateWorks granted $300,000 in funding for the technical team developing the agenda to support engagement across African countries and civil society. We will also have staff attend the summit to meet with local partners, listen, and learn.

We believe philanthropy’s engagement is essential to catalyzing transformative action in Africa, and we look forward to growing our collaboration with local organizations working on the ground to propel the continent toward climate-resilient development.

August 16, 2023 marks one year since President Joe Biden signed the historic Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) — the boldest action thus far by the United States to reduce climate pollution and accelerate the transition to clean energy — and one with sweeping ramifications for global efforts to address climate change.

The IRA includes massive investments in climate provisions and is expected to reduce US net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by around 40% from 2005 levels by 2030, all while delivering a wide range of health and economic benefits for Americans. Implementing the law could also help create more than 9 million jobs over the next decade, according to an analysis by the BlueGreen Alliance. Additionally, the IRA represents the most significant step taken to date by the United States toward its commitments to the Paris Agreement on climate change — an international treaty with a goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5° C relative to pre-industrial levels.

The IRA is the culmination of decades of efforts led by communities and grassroots movements, with support along the way from environmental groups, government and business leaders, and a wide range of additional allies. Over the years, philanthropy played a pivotal role in these efforts, working behind the scenes in collaboration with the private and public sectors and civil society actors to support the sustained engagement that helped make this bold climate action possible. Moving forward, philanthropy must not only support efforts to implement the IRA but also push for even bolder action on climate change.

Philanthropy helped pave the way for the Inflation Reduction Act

Shortly after the IRA was signed in August 2022, Inside Philanthropy’s Michael Kavate chronicled the role that philanthropy played in helping achieve the historic law. For example, philanthropy has provided consistent support for climate movement building over the years, backing groups such as the 501(c)(3) arm of the Sunrise Movement, whose efforts were critical for building sustained momentum for ambitious federal policy on addressing climate change.

Philanthropy also backed major initiatives that shaped many of the policies outlined in the legislation. ClimateWorks is proud to have supported a number of organizations that have worked over the years both to achieve the passage of the IRA and to shape its climate provisions.

One notable example of philanthropy’s influence on the IRA is the law’s ambitious provisions for transportation electrification. Supported by philanthropy, partners within the Drive Electric Campaign — a global initiative accelerating electrification of all road vehicles by 2050 — spent years on coalition-building and groundwork to push Congress for robust investments in electric vehicles (EVs), with a wide range of approaches including education, strategic communications, and coalition sign-on letters. This work proved fruitful as transportation electrification became a centerpiece of the IRA, which wound up including nearly all the provisions advocated for by Drive Electric partners. Such provisions include expansive tax credits for EVs, used EVs, and commercial clean vehicles; grants that will help accelerate the shift to zero-emission buses and heavy-duty vehicles; and major incentives for the retooling of existing facilities to manufacture clean vehicles and batteries. Crucially, these provisions will increase access to electrified transport for all by completely changing the calculus of the deployment timeline for electric cars, trucks, and buses, delivering cleaner air to hundreds of thousands of Americans by 2050.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is another element of the IRA that reflects ongoing philanthropic involvement. Sustained engagement by philanthropy — including support for critical research, analysis, and advocacy — helped contribute to transformative new incentives and provisions in the bill that support technological and land-based carbon removal. In particular, the IRA includes refinements to the 45Q tax credit that will enable it to better support carbon removal startups and allow a broader range of project developers to take advantage of the credit. These improvements could help deliver up to $100 billion in new investments. Already, there is significant momentum for CDR projects, especially given there are also strong CDR provisions in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Just last week, the Department of Energy announced funding that will support the early-stage development of various regional direct air capture (DAC) hubs, including one in California’s Kern County that ClimateWorks has been supporting for nearly three years.

The road ahead: Implementing the IRA and pressing for even more climate action

The one-year anniversary of the IRA marks an important crossroads not only to reflect on how the legislation was achieved but also to focus on the work ahead. It is critical that philanthropy support the implementation of the IRA while also helping address the gaps that still exist in needed climate action.

While the IRA represents a landmark achievement, now is the time to ensure that the actual implementation of the legislation is timely, effective, and benefits communities. The success of the IRA will require businesses, individuals, state and local governments, and community partners to take advantage of its tax credits and other incentives. Philanthropy must continue to work closely with partner organizations that have the networks and expertise to support the implementation of the IRA. And there are new efforts already underway: Invest in Our Future, for example, was launched by five of the country’s largest climate funders and is working to help communities (including rural and low-income communities, communities of color, and Native communities) benefit from the IRA — which includes navigating the complex process of applying for federal funding. Similarly, a number of environmental and climate justice networks have organized regional hubs that will help community-based organizations secure federal funding for environmental justice projects.

Additionally, philanthropy can play a role in advancing efforts that will help fill gaps in the IRA and in the country’s climate efforts more broadly. For example, as discussed earlier, the IRA is expected to produce a 40% in reduction GHG emissions by 2030 — but this still falls short of the 50% to 52% in reductions needed for the United States to meet its Paris Agreement commitments. Even in the case of zero-emission transportation — arguably the largest suite of IRA investments — ambitious federal regulations are needed to meet climate goals for the sector. Philanthropy should continue to support the groups, movements, and communities that are looking at the IRA and beyond to help ensure the United States is on a clear path to meeting its commitments. One emerging area of philanthropic collaboration, for example, involves addressing industrial emissions, where additional action offers the United States a path to get closer to achieving Paris targets.

Philanthropy can help address additional areas that are under-addressed by the IRA. For example, while the IRA includes historic investments to advance environmental justice, activists have argued that the provisions are insufficient, especially considering the bill also contains some concessions to the fossil fuel industry. These shortcomings are a call to action for philanthropy to prioritize the people most impacted by climate change.

Philanthropy must keep pushing forward

A year after its signing, it is important to celebrate the momentous achievement the IRA represents for climate action, the expansive efforts that made it possible, and the wide range of benefits it will bring to communities. It is also an opportunity for philanthropy to reflect on its role in supporting the movements, groups, and organizations that pushed for this historic legislation and whose work is reflected strongly in its policies.

Nonetheless, it is clear that philanthropy must support grantees’ efforts to help implement the emissions reduction potential inherent in the IRA, as well as push for additional climate actions needed to limit global temperature rise to 1.5° C and avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The one-year anniversary of the historic IRA should be celebrated because it offers the United States its greatest opportunity ever to build a more just, equitable, and clean energy future for people and communities across the country. The apocalyptic wildfires in Maui this past week provide yet another horrifying and somber reminder that climate change is already a deadly reality for people and communities in the United States and around the world. It should serve as a motivator for philanthropy to build off of the momentum created by the IRA and to keep pushing for faster climate progress now.

The Empowering People Initiative (EPI) is working to advance energy transitions that can support the current and future workforce.

Renewable energy is our future — and there is significant momentum behind efforts to phase out fossil fuel and accelerate energy transitions. Now, the big question is “how?” How do we build a robust worker pipeline to drive the sustainable economies we are building? And how do we ensure communities benefit from these transitions? We start by investing in policies and strategies focused on communities and workers impacted by energy transitions.

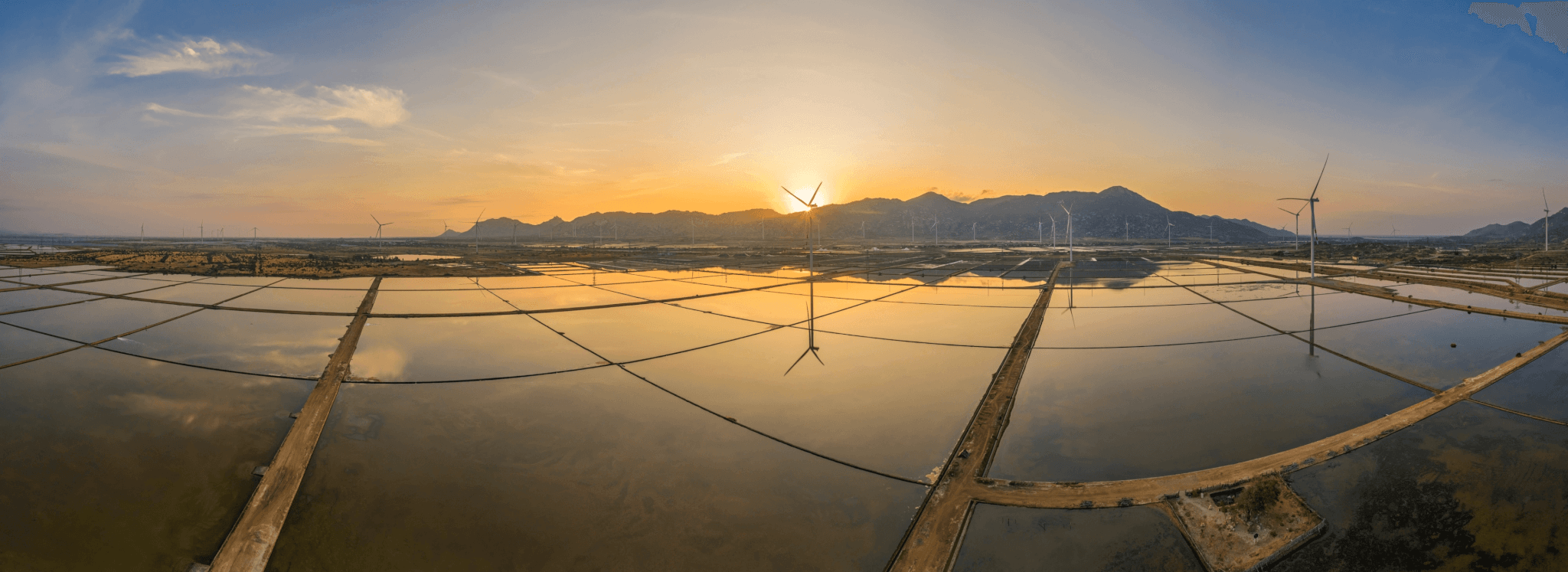

In 2021, the announcement of the Just Transition Declaration during COP26 in Glasgow — which included signatories from the United States, Canada, the European Commission, and the United Kingdom — signified a commitment to building pathways for businesses, communities, and workers to transition from carbon-intensive sectors towards a greener and more sustainable global economy. The emergence of Just Energy Transition Partnerships in South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Senegal looks to mobilize billion-dollar investments for accelerated clean energy transitions in emerging economies. A 2022 report on Skills Development and Inclusivity for Clean Energy Transitions from the International Energy Agency predicts a “paradigm shift” in the energy workforce, with 14 million new jobs created by 2030 and an additional 16 million requiring green skills to operate effectively in the new, clean economy. This shift will reverberate across the workforce value chain, impacting millions of workers who depend on these sectors for their jobs and livelihoods.

In 2022, ClimateWorks Foundation partnered with the Clean Energy Ministerial’s Empowering People Initiative (EPI) to address the socio-economic elements of the energy transition — supporting people-centered approaches that advance skills, inclusivity, and effective workforce development as countries continue to develop transition pathways towards renewable energy sources.

To better understand how government, the private sector, labor union groups, youth, philanthropy, nonprofits, and other groups can work together to build and prepare for the emerging workforce that the clean energy transition will bring, I spoke with Laure-Jeanne Davignon, EPI Coordinator, and Dr. Melisande Liu, Partnerships Manager with CEM. Together, they shared about what it takes to advance equitable energy transitions that support current and future workforces.

What drove CEM to create the Empowering People Initiative?

The Clean Energy Ministerial (CEM) is a high-level global forum focused on accelerating equitable clean energy transitions around the world. CEM promotes policies and programs to advance clean energy technology by sharing best practices and diverse experiences. The effort has united the countries responsible for more than 90% of clean energy generation capacity, with innovative programs impacting the power, industrial, transportation, and investment sectors.

In June 2021, Canada, the United States, and the European Commission launched the Empowering People Initiative (EPI) to highlight the critical socio-economic elements needed to fuel just and equitable transitions. The EPI provides a unique forum for diverse voices and the development, implementation, and scaling of policies and practices in the areas of skills advancement, inclusion, and workforce development for the energy transition. The EPI was created as a horizontal initiative to recognize a scope of work that was underemphasized under the CEM while also building on and complementing existing work streams.

What are EPI’s core intervention areas?

EPI currently focuses on three core intervention areas — the first of which is skills development. By partnering with institutions such as LinkedIn, the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Energy Agency (IEA), the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), and the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), EPI seeks to better understand key labor market trends and the skills and training required to ensure the uptake and deployment of low-carbon technologies in this critical decade for tackling climate change. One of these recent knowledge examples includes the collaboration with IEA on the 2022 report “Skills Development and Inclusivity for Clean Energy Transitions.”

A second core intervention area involves policy planning and implementation for a green workforce and economy. As a government-led international cooperation initiative, EPI facilitates a policy environment that promotes a more diverse and inclusive energy workforce, develops programs, and ensures that people-related issues such as skills, employment, and workforce are recognized as key pillars and opportunities for the clean energy transition and that workforce pathways adhere to key principles such as inclusion and fairness.

Finally, EPI is focused on preparing the green workforce at local, regional, and national levels. EPI is able to support workforce development planning at these levels by bringing together governments responsible for workforce, employment, and curriculum development, allied industry partners, labor, nonprofit and education groups from around the world, and providing first-hand access to information, networks, best practices and solutions for effective workforce processes.

Can you describe the Integrated Policymaking and Empowering Communications for the Clean Energy Economy and Workforce (IPEC)?

IPEC is a project launched by EPI with funding support from ClimateWorks. It addresses the need for governments and government departments to move beyond working in silos on workforce issues and give them access to specific resources, tools, and communities of practice that enable them to become change agents within their institutions. In doing so, EPI is able to support governments in developing more holistic and integrated policies and programs for workforce preparation and just transition, and in overcoming fragmented approaches across relevant ministries. To date, IPEC has convened more than 400 participants from 100 countries who have responded to the call to accelerate solutions to support just transitions, including strong representation from countries in the Global South. Outcomes of the project’s first phase include four live interactive Solution Summits, a compendium of resources, and a toolkit for policymakers, to be released this month.

What are the most significant gaps in the current global energy transition ecosystem?

Today, commitment to tackling climate change is at an all-time high, with a chorus of countries announcing net-zero pledges. Countries will embark on their energy transitions from different starting points, highlighting the importance of ensuring that net-zero pathways are fair, inclusive, and leave no one behind. The energy transition is built on the understanding that there will be major shifts toward existing and early-stage technologies across economies and value chains — and countries will need to ensure that their workforces are prepared to adapt to these changes. These major disruptions need to be considered holistically and carefully coordinated across jurisdictions and government departments to ensure that skills are transferred from the fossil fuel sectors to the renewable sectors.

At the same time, the operating environment can be challenging and co-exists within pre-existing societal and educational frameworks. These include, for example, the much-touted “skills gap,” wherein educational systems are not preparing students with skills aligned with employer needs, or workplaces that are not prepared to welcome workers from a range of multicultural and diverse backgrounds.

To implement ambitious clean energy and decarbonization goals, talent must follow, and recruitment, development, and retention of the new and transitioning workforce must be inclusive and accessible. There is a lack of awareness of career opportunities in the clean energy sector in many emerging markets. Even where awareness exists, career and educational pathways are not always clearly defined or accessible, especially for those historically excluded from the workforce, such as women, racialized people, economically underprivileged, and other historically underrepresented groups.

While workforce development programs and policies exist, there continues to be a lack of available data across many economies, coordination between entities, and available resources — finance, funding, and capital — to scale workforce programs and clean energy growth. The lack of comprehensive labor market and other data to inform integrated planning, such as cross-sector policy and program frameworks, can often hinder coordination efforts. Overall, there needs to be more coordination to collaborate and develop the workforce ecosystem and facilitate just transitions. Lastly, for the needs listed above to be met, the streams of international public and private financial resources will need to grow substantially and with dependable regularity.

What does EPI see as critical next steps and lever points to advance equitable clean energy workforce development?

The most acute need is effective coordination by groups like CEM to ensure governments and other enablers are not operating in silos and can share best practices and scale solutions. Many tested best practices and solutions are already out there, but there needs to be more awareness, communications forums, and the visibility and resources to scale.

To match the speed and scale required for clean energy transitions, we must equally scale up and build capacity across the workforce value chain. Better coordination is critical across countries and regional educational, curricular, and accreditation bodies and employers and private sector institutions to facilitate the integration of clean energy and sustainability principles into existing educational and professional development frameworks. Tools and resources for trainers and other interest groups must be readily available and up to current standards.

Widespread outreach targeting youth and transitional workers needs to be prioritized, as they are well-positioned to be ‘energy heroes’ and can raise awareness about career opportunities and provide information about diverse career pathways into the industry. Climate and energy policies and programs developed at the local, regional, and national levels must integrate meaningful provisions for workforce development and just transitions. Finally, to ensure equitable clean energy transitions, access to resources and funding are necessary at the local community level to remove barriers to entry into the workforce.

Where does philanthropy have the most impact on facilitating a global just energy transition?

Philanthropy is invaluable when it can be flexible and responsive in ways that help advance innovation and create opportunities for people and communities, including youth and historically underprivileged groups, during the energy transitions. It can help develop tested solutions ripe for scaling through other funding streams. Specific areas in which we see philanthropy significantly impacting the just transition are efforts to leverage established community organizations to provide new pathways into clean energy careers and support coordinating entities with the networks and expertise to scale solutions across regions or markets.

What are some other priority initiatives CEM is working on this year?

Governments are vital in setting the strategic and decisive directions for the whole-of-society clean energy transitions, but they cannot drive them alone. Key allied interest groups, including employers, education and training providers, local government and community organizations, and funders and program implementers such as foundations and utilities, all play a critical role in an equitable transition. EPI proposes to build on our success with the IPEC effort to host convenings and produce resources for these audiences focused on building healthy networks to scale solutions, improving processes for recruitment, training and education, and job placement, as well as building market demand for clean energy transitions.

We are also building our community of membership to ensure diverse representation and a focus on supporting countries and communities that are disproportionately suffering from the impacts of climate change.

Laure-Jeanne Davignon, Coordinator for the Empowering People Initiative, has spent over two decades in workforce development, most recently as a Vice President managing oversight and strategic direction for a national clean energy workforce program in the United States. She lives in the State of New York and powers her home through one of the State’s first community solar projects.

Dr. Melisande Liu, Partnerships Manager, joined the Secretariat of the Clean Energy Ministerial (CEM) in February 2021. Her portfolio includes the coordination of CEM workstreams on long-term energy scenarios, green skills and workforce, global and regional energy interconnection, and investment and finance, as well as country engagement with Brazil, Chile, China, Germany, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, and the United Arab Emirates.

Filling an investment gap of trillions is critical to realizing energy transition, climate, and development objectives, and 2023 should be a year of unprecedented focus on increasing investment in these areas in emerging and developing economies (EMDEs).

A recent landmark report estimates annual climate investments in EMDEs other than China must reach $2.4 trillion by 2030 — a four-fold increase. Of this, $1.5 trillion will need to be dedicated to transforming the energy system, and around $1 trillion would be international flows from private investors, multilateral development banks, and others, all against a challenging international backdrop of multiple crises and geopolitical tensions leading to widespread stagnation in investment levels.

Mobilizing private finance is vital and is expected to provide around 70% of the financing for capital-intensive clean energy technologies and low-carbon solutions. Past efforts to enhance the mobilization of private investment and finance, including those by multilateral development banks (MDBs) and other public finance institutions, have had limited success.

At the same time, private investors often point to barriers to energy transition investments in many EMDEs related to sector policy and regulatory factors such as permitting for clean energy projects, connections to the grid, fossil fuel subsidies, and uncertainty about off-takers’ ability to honor contracts. Barriers and risks in the energy-related sectors, the financial sector, and the broader economy delay the energy transition by limiting the supply of investable projects and increasing the cost of financing.

It will take a systems approach to get to “the trillions”

Effective investment and finance mobilization must integrate climate and development objectives and country, sector, and international dimensions. New Climate Economy, OECD, and others have repeatedly brought forward this message.

Development and energy transition priorities must integrate to create an attractive investment climate and robust pipelines of energy transition investment opportunities. This integration requires deploying a range of coordinated measures such as a 1.5° C-aligned energy transition pathway, energy system investment planning, enabling clean energy policy and market regulation, and targeted risk-sharing instruments. Altogether these measures have the potential to turn energy transition investment needs into pipelines of investment opportunities.

At the national level, a whole-of-economy and whole-of-government approach covers all of the real economy sectors that are part of the energy system (i.e., energy supply, industry, buildings, and transport), the financial sector, as well as macroeconomic and crosscutting dimensions, such as trade, industrial policy, and taxation.

The international ecosystem also plays an essential role in mobilizing investments and finance. However, current international support for country energy transitions tends to be a patchwork of bi- and multilateral efforts operating in silos, which, together with limitations in the international toolbox of catalytic instruments, reduces the effectiveness of international cooperation and support.

A practical framework for catalytic action will require international actors to align and support government-led country transitions. An integrated approach must address interactions between the international and country systems in the real economy and financial sectors, along with barriers at the international level and within the countries supplying clean energy technologies and finance.

Catalytic action for systemic impact

Focused efforts in five priority areas can prepare the international ecosystem for catalyzing investment in country and sector transitions:

1. A commitment to catalyze

MDBs and other public financial institutions must reorient their operating models toward an emphasis on mobilizing “the trillions” — particularly when it comes to investment in energy-related sectors and in middle-income countries where mitigation efforts are most urgent. A tangible approach would be a commitment to catalyze that could include a range of direct and indirect functions to support mobilizing investments and finance. Commitments should be impact-oriented and specific enough to drive adjustments to the operating models of the MDBs. KPIs should also incentivize MDBs to take responsibility for the effective functioning of the international ecosystem of support for country energy transitions and investment mobilization.

Other public financial institutions such as bilateral development finance institutions, national development banks, and central banks also play catalytic roles and should consider taking similar steps. The IMF is also expanding its role within the international ecosystem, raising additional capital by channeling Special Drawing Rights and developing new ways to support climate action. Beyond public financial institutions, other international institutions must consider how they can do more to make their specific expertise and resources available in support of catalytic efforts.

2. Risk mitigation instruments

There is widespread recognition of the need to address real and perceived risks associated with private sector investment and finance in energy transitions. Frequently highlighted risks include macro risks, such as exchange rate risks, regulatory risks related to permitting, and credit risks, such as off-taker risks for clean energy supply. Because unmitigated risks limit the supply of investment opportunities and increase the cost of capital, there is a need to develop and capitalize specific instruments that offer standardized risk mitigation instruments available to public and private actors at scale and with low transaction costs.

3. Vehicles and platforms to channel institutional capital

Various vehicles and channels are part of the “plumbing” that allows international finance to flow to real economy investments in EMDEs. Solutions exist inside and outside capital markets, channeling equity and debt, such as green bonds, for climate-related investments. Blended finance can improve risk/return profiles of investments, but there is a need for further work on the design and deployment at scale.

4. Country and sector platforms

There is increasing interest in comprehensive approaches to cooperation around accelerated country transitions. The Just Energy Transition Partnerships in countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa are becoming test cases for efforts to mobilize and align international donors and private investments to accelerate developing economies’ energy transition.

Country and sector platforms may connect national and international ecosystems and help align public and private, real economy, and financial actors around cooperation to mobilize investments and finance at scale for the transition. While there are no off-the-shelf playbooks for structuring platforms and transition partnerships, there is enormous potential for more streamlined international cooperation from further developing and deploying such models.

5. Addressing supply-side barriers

Faced with the challenge of scaling up investments both at home and abroad, wealthy countries need to ensure a corresponding increase in savings and address any “home-grown” impediments to channeling part of these savings into investments in EMDEs. Supply-side barriers may be related to regulations and practices within the countries supplying the investments or to international regulations and agreements.

Making it happen: Taking advantage of opportunities in 2023 to step up action

Improving the international architecture around investment and finance for the energy transition, climate, and development is high on the agenda in 2023 and beyond. This week’s Summit on a New Global Financing Pact offers a high-level moment for new approaches to catalyzing investments and finance, the G20 and the UNFCCC have called upon MDBs to adjust their operating models and scale up mobilization of climate finance, and the UAE COP28 Presidency has made investment and finance a priority theme.

Many efforts to develop actionable solutions are ongoing, creating several opportunities for governments, philanthropy, and the private sector to step up their contributions. In doing so, they should consider two areas in which scaled-up catalytic funding is essential.

- Investing in human and institutional capacity to make the economy function more efficiently, generate pipelines of investable opportunities, and connect them with domestic and international finance. These “soft investments” are often underappreciated and underfunded.

- Using seed funding and capital injections for risk mitigation and blended finance instruments. These will require significant nominal capital commitments, although the actual cost (e.g., reflecting realized losses on a guarantee instrument) will typically be much smaller.

Sustainable development and climate objectives require massive investments in the energy transition. Realizing this will require governments, the private sector, and institutional actors to rally behind ambitious investment strategies. Moreover, actions will be most impactful if they build on a shared effort to make the international ecosystem more effective in catalyzing investment and finance.

A new tool helps users navigate the many open climate data platforms available and identify the most relevant platforms for their work.

The 2015 Paris Agreement outlines the mitigation, adaptation, and financial transitions required to respond to current and future climate change impacts and champions a just transition to help the communities most affected. The systemic transitions needed for a climate-safe future will require many types of data — including at both the country and city levels, across both adaptation and mitigation measures, and efforts to address both public officials and the private sector.

The good news is that many aspects of climate change are measurable, and this data can help identify problems, inform decisions, and set up timely information systems. Data platforms — websites that let users view, explore, and download a variety of datasets — have emerged to support the curation and sharing of this growing ecosystem of climate data.

However, with hundreds of platforms available, it can be difficult to find the best data for your particular needs or to know where data gaps still exist. To remedy this challenge, we created a map of open climate data platforms called the Climate Data Platforms Explorer to help users find the most relevant platforms for their work, understand which initiatives are underway, and identify where new research can add the most value.

The explorer shows a matrix of more than 100 major data platforms identified through this process1, displayed by topic (x-axis) and geographic level (y-axis). Tools that cover several topics or scales are shown multiple times. Platforms were selected for inclusion based on a set of criteria including the relevance of data for climate change science, policy, and action; a relatively broad geographic scope; reasonably up-to-date data; and robust methods.

The Climate Data Platforms Explorer allows different users to discover the most relevant data for their work using filters in a visual format, a filterable table, or a download of the raw data. In curating this dataset of major platforms, we identified several notable patterns in the climate data ecosystem.

Most data platforms focus on mitigation, energy, and country-level data

A majority of data platforms focus on climate change mitigation — addressing greenhouse gas emissions and the economic activities that cause them — and on the energy sector. Both areas are core concerns: addressing climate change requires rapid decarbonization, and the energy sector is responsible for 76% of global emissions. Similarly, there is greater coverage at the country and regional levels than at more granular geographic levels.

There are significant gaps in data and platforms around topics that are harder to measure like equity, policy, adaptation, and resilience, and at the subnational level. Accessible data is needed to support climate change across sectors and different actors, including through city, corporate, and local climate action. Adaptation efforts, in particular, require local data that is often unavailable or insufficient.

A new platform isn’t always the solution

We identified many similar platforms that showcase relatively similar datasets. It is not always clear that these datasets needed to be hosted on an entirely new platform, and they may have been more effective if integrated into existing resources.

Any new platforms — and new datasets powering these platforms — should ensure that they build on existing efforts, align with previous standards, and show that they provide actionable data. In considering new work, project leads should first engage in robust scoping to understand what the most urgent and actionable data gaps are, and how new datasets or new data platforms might or might not fill these gaps. This should include interviews with both supporters and skeptics, as well as user testing to understand what target audiences need from a platform and whether the planned platform would be able to meet these needs. Second, we also suggest exploring simpler ways to make data available to potential users before building out a complex website — such as a simple provision of the raw data with summary tables and a brief methodological explainer. Finally, while the transaction costs of collaboration can be challenging, we encourage practitioners to consider whether they can meet their aims by incorporating their datasets into existing platforms rather than building out new tools.

Data maintenance plans are sometimes an afterthought

Some of the platforms that we assessed for this project appeared to be carefully built, but are no longer maintained. We encountered a variety of issues, including server problems, broken data links, visuals that relied on outdated software, or outdated data. In some cases, there may be good reasons for these issues — for example, a platform may have relied on a dataset that was retired, or the research was time-bound. However, in other cases, the problems were tied to age-old problems, such as lapsed funding, staff turnover, or a lack of capacity for maintenance.

If a new platform appears warranted, its maintenance should be a prime consideration. Building an entirely new data platform has costs, and limited research funds could be put to more urgent use than this creation-and-abandonment cycle. It is essential for researchers to build long-term maintenance plans and for funders to be clear about the potential for longer-term support or lack thereof.

Building a better climate data system

It is clear that we need to improve our climate-related data infrastructure. As suggested earlier, the requisite data often exist, but they are collected by different types of users for different purposes, and scattered across multiple platforms with varying standards. Consequently, it is difficult to discover and use this data for real-world applications.

To address these problems, we need to articulate a vision of a system of open, shared, and integrated data. Ideally, existing climate data would be open by default, discoverable, and digitally accessible; data standards to promote interoperability, efficiency, and user flexibility would evolve in response to user demand; and researchers, funders, governments, and NGOs would fill data gaps by sharing high-quality data, along with essential metadata. These actions could lead to an interconnected system of public-facing climate data to meet the diverse needs of data users. The first step in creating a connected climate data ecosystem is identifying credible climate-relevant data platforms around the world.

The Climate Data Platforms Explorer offers first steps in this direction by curating a set of climate data platforms to support users in finding the most relevant platforms for their work, providing a picture of what work is already underway, and identifying where new research can add the most value.

A call to action for researchers, funders, and governments

Researchers, philanthropic funders, and governments can take the following steps to move toward a more connected and rationalized climate data ecosystem. If you are considering any new platforms, we suggest that your work should:

- Avoid redundancies and confirm user needs: Conduct due diligence to ensure that new datasets and platforms are complementary to and not redundant with existing efforts — and that they address confirmed user needs. Where possible, build with or on existing platforms and standards rather than launching new projects. Those creating or commissioning new data should consider earmarking support within project budgets to enable this due diligence, user testing, and the increased transaction costs that collaboration can require.

- Be open, interoperable, and discoverable: If new datasets and/or platforms prove necessary, they should be designed to be open and interoperable, allowing data and metadata to be shared within existing repositories. Good metadata could enable a decentralized interconnected system — similar, for example, to Data.gov, in which data creators could submit their data and platforms to a central inventory.

- Include a plan for long-term maintenance: Finally, it is critical to plan for the maintenance of the dataset and the platform on which it lives over time. Questions to consider include: is the platform tied to a time-bound event or will it exist in perpetuity? Is there a plan to sunset it if new data is not forthcoming? Who on the team owns ongoing maintenance tasks, and is there a budget earmarked for repeating costs such as hosting services? Funders can support these efforts by surfacing these questions before supporting new work and building longer-term support into project budgets.

We invite you to try the Climate Data Platforms Explorer and to submit new data to make the Explorer more complete.

Special thanks to Sam Lumley and Denisse Del Monte for their partnership on this project.

1 The list of platforms is derived from databases curated by World Resources Institute, ClimateWorks Foundation, and McGill University. This list is not comprehensive, but we welcome submissions of major resources that we may be missing. Please submit through this form.

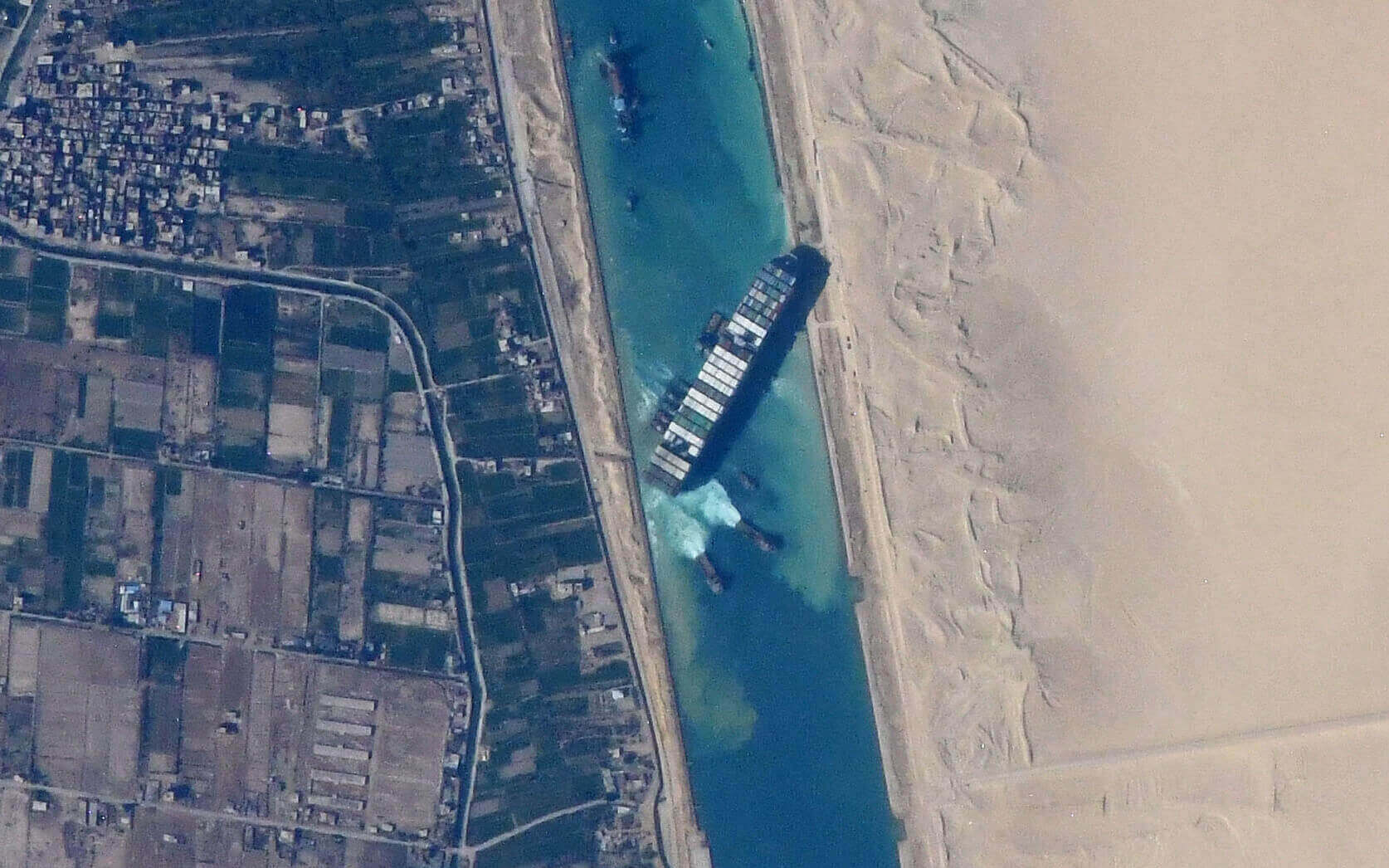

In March of 2021, a ship the size of the Empire State Building called Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal, crippling global trade to the tune of $10 billion a day and inundating social media with memes poking fun at the pathetically wedged-in vessel. The incident added to the supply-chain woes of the coronavirus pandemic, when consumers around the world seemed to realize for the first time that the boxes landing on their doorsteps had arrived there thanks largely to journeys by sea. And yet for all the attention recently enjoyed (or suffered) by maritime shipping, the sector’s real news — a fast-moving decarbonization movement — was playing out behind the scenes.

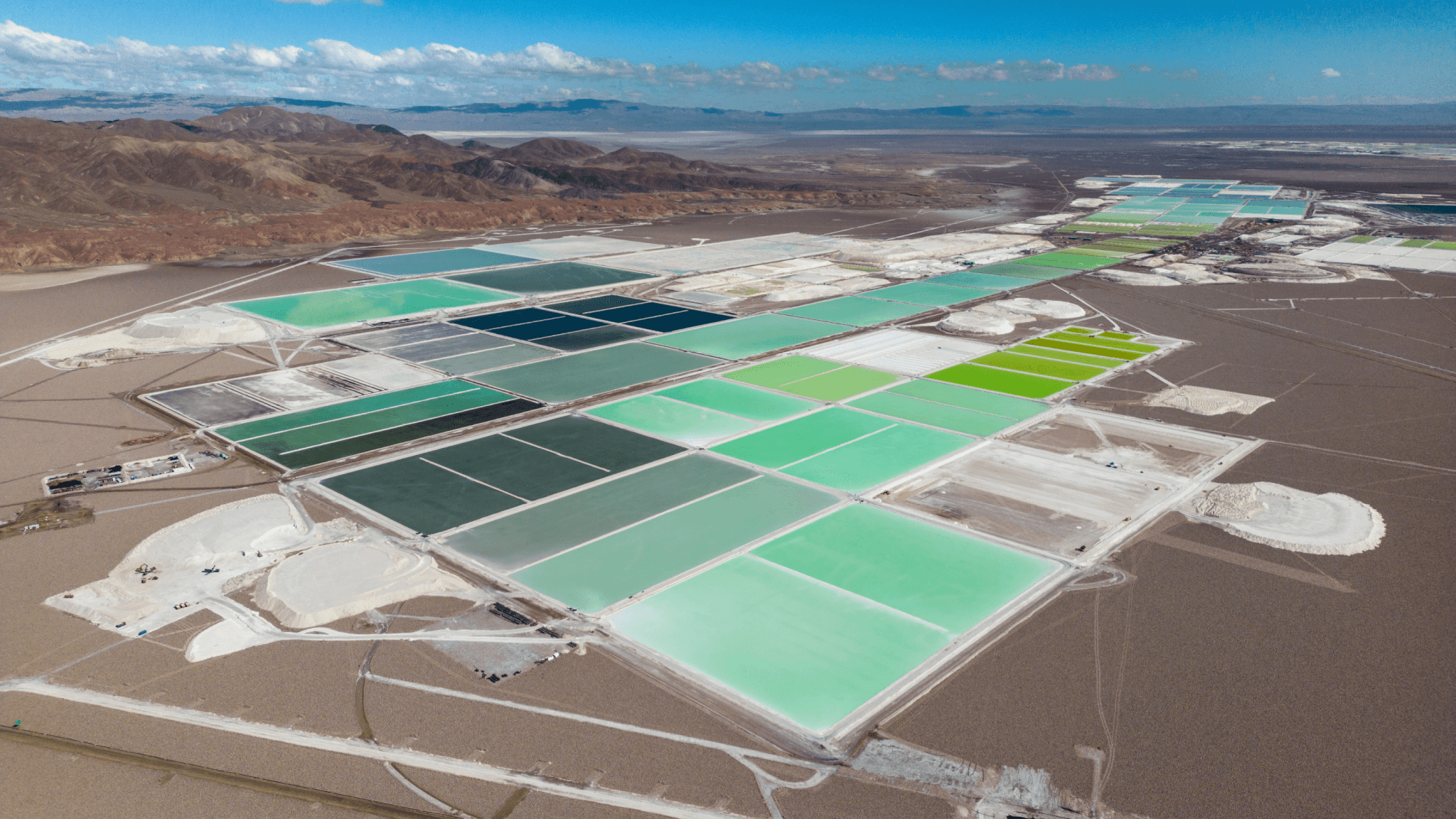

The general public may finally know something about cargo ships and containers, but few may realize the extent to which the multi-trillion-dollar shipping industry pollutes our planet. The sector is responsible for 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions — as much as aviation — and its emissions could double by 2050. Ships run mainly on the thick sludge that remains at the end of the oil-refining process, and if we are to limit the increase in global temperatures to 1.5° C, we will need to transition to energy sources with much lower carbon footprints. That will mean figuring out what those sources are — green ammonia and green methanol are the leading contenders — and then overhauling our ships and building new port infrastructure to support them.

Unfortunately, the industry’s unique character — with activities taking place mostly on the high seas so no single country takes responsibility, and owners registering vessels in whichever jurisdiction promises the least expense and oversight — has made it harder for countries to take meaningful action on their own. And efforts to cut emissions through international regulations have been routinely met with resistance from shippers and oil companies. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), the U.N. agency that regulates international shipping, has announced a goal to at least halve ship emissions by 2050, but that target would be both too little and too late.

At ClimateWorks Foundation, we know that there isn’t time to waste. Our grantees are working with partners all along the value chain — from port operators, ship owners, and carrier companies to the consumer-facing brands that rely on shipping — to decarbonize everything, fast. Many of the solutions needed to transform international maritime shipping into a zero-emissions industry by 2050 aren’t yet on the water, but we’re collaborating with civil society organizations, portside communities, and the private sector to reshape the commercial and policy environments to accommodate them when they arrive.

Among the most promising initiatives we’re supporting are green shipping corridors. In 2021, at the COP26 meeting in Glasgow, the U.K. government announced the launch of the Clydebank Declaration for green shipping corridors. These are routes between two major port hubs in which the technological, economic, and regulatory conditions are in place to support the operation of zero-emission ships. Signed by 24 governments, the Declaration, which pledges to establish half a dozen such routes by 2025, is meant to cut through the complexity involved in decarbonizing shipping. The goal is to inspire actors, both public and private, to make early-mover commitments and take on projects that jumpstart a sector-wide transition and move the industry toward its goal of a tipping point of 5% green fuels by 2030.

In addition to providing a way for local, state, and national governments to move forward independent of the IMO, the corridors help address a chicken-and-egg problem that’s currently holding transition efforts back. Ship and port owners are reluctant to invest in vessels and bunkering facilities that use expensive alternative fuels until they know which ones are likely to be adopted — and that they’ll be available where needed. But only widespread adoption by those very actors will achieve the economies of scale necessary for the fuels’ prices to fall. Our partners at theAspen Institute have put together a network, Cargo Owners for Zero Emission Vessels (coZEV), of major freight customers such as Amazon and IKEA who are stepping up their commitments as a way of indicating to shipping leaders like Maersk that demand for green-shipping is emerging and that they should begin shifting their fleets toward cleaner vessels. “In the end,” says the Institute’s Ingrid Irigoyen, “it’s about the money. Can you afford to make the transition?”

“Ports have become some of the most acute centers of fossil-fuel pollution on the planet. You have ships, trucks, trains, planes, and all these goods and personnel moving through, and almost all of it is run by fossil fuels.”

— Madeline Rose, Pacific Environment

But going green isn’t just about climate change. As Madeline Rose, the campaign climate director for our partner Pacific Environment, points out, “Ports have become some of the most acute centers of fossil-fuel pollution on the planet. You have ships, trucks, trains, planes, and all these goods and personnel moving through, and almost all of it is run by fossil fuels.” Most ports remain overwhelmingly powered by diesel, a fuel that disproportionately affects the health of people living in port communities by causing high levels of localized pollution. At the Port of Los Angeles, for instance, which is the busiest container port in the Western Hemisphere (it handles roughly 40% of U.S. imports), ships now surpass trucks, rail, and cars in emissions of nitrous oxide and particulate matter to portside communities. Populations surrounding the L.A. port have the region’s highest cancer risk from air pollution, and they have higher rates of asthma compared with the rest of the state.

That’s why we’re particularly excited about a green-corridor initiative involving Shanghai and Los Angeles, one of the world’s busiest container shipping routes. The cities’ ports announced a partnership facilitated by C40 Cities in early 2022, with a pledge to reduce emissions from the movement of cargo throughout the 2020s. They will also begin transitioning to zero-carbon-fueled ships by 2030.

The project evolved thanks in part to a campaign called Ports for People, spearheaded by Pacific Environment and communities in port hubs pressuring their local and state governments to address the environmental problems posed by their facilities. The coalition was instrumental in pushing the state of California to pass a zero-emissions ferry mandate, which in turn led South Korea, Japan, and Singapore to announce similar rules. In California alone, the move is expected to reduce the cancer risk for 20 million people and to save the state millions of dollars in public health expenditures. Advocacy by grassroots partners also helped force the state to approve a rule ordering ships calling on its ports to switch to low-sulfur fuels and requiring most of those docking at its largest ports to connect to shore power. The rule also required cleaner engine upgrades for its tugboats and other harbor vessels. Since then, the L.A. and Long Beach ports have spent hundreds of millions of dollars building the electrical infrastructure.

Pacific Environment was also involved in the 2021 launch of the Ship It Zero campaign, calling on retailers such as Target, Walmart, IKEA, and Amazon to transport their products only with carriers “taking immediate steps to end emissions” and to sign contracts promising to begin shipping their goods on the world’s first zero-emissions ships. As with coZEV’s, the group’s outreach has helped to prod the big retailers toward bolder carbon-related commitments. Among its more dramatic actions was an eight-minute “die-in” held last spring at a Long Beach Target (the chain imports 98% of its goods through L.A. and Long Beach) to highlight the eight-year discrepancy in life expectancy between port communities and the general public. Through their combined efforts, they are continuing to shift perceptions — in the industry and beyond — as to the sort of systems-wide transformation that might be possible.

A campaign called Say No to LNG aims to remind shippers, retailers, and the public that liquified natural gas, despite its greenwashed image, does not qualify as a cleaner “bridge fuel.” The methane-heavy substance is in fact a devastatingly heavy polluter, and it should have no place in green corridors or anywhere else in a sustainable shipping future. Shippers who retrofit their vessels to accommodate such an obviously not-long-for-this-industry option are setting themselves up to lose billions in stranded assets.

Groups in China, home to the world’s biggest ports, greatest shipping volumes, and leading shipbuilders, are working on an energy-efficiency design index to develop standards for domestic vessels in the country and are helping to establish green corridors within Asia. Our research partners also have begun ranking Asian ports on the various technologies they’ve adopted — whether shore-power infrastructure or electric forklifts — and making those assessments public as a way to inform citizens and pressure local officials to raise their climate-related commitments. Local officials, in turn, can lean on port operators and shipbuilders to better address the emissions and other pollutants resulting from their operations.

Partner organizations in the European Union are helping to advance the bloc’s already ambitious climate goals. They were instrumental in pushing the European Union to pass a recent law adding shipping to its Emissions Trading System. Ships must now pay a per-ton carbon tax on all greenhouse gas emissions generated by intra-EU voyages and on half the distance from extra-EU voyages, as well as on emissions resulting from berths in EU ports. A second law will require ships to begin switching to low-carbon fuels starting in 2025. Our partners at Transport & Environment, based in Brussels, are working to create a legal framework around green corridors in the region and to ensure that any claimed emissions reduction can be transparently monitored and, at a later stage, enforced.

At Opportunity Green, based in London, and Seas at Risk, in Brussels, our partners are focused on using legal avenues to enable national governments beyond the European Union to be more proactive about cleaning up their maritime-shipping industries. They are pushing for a global carbon levy on shipping and a just and equitable transition for the sector. They argue, for instance, that money raised through a levy scheme should go toward loss and damages suffered by countries in the Global South and that the shipping industry of the future must support decent jobs and improved health outcomes in all countries involved. This means, among other things, helping countries like South Africa and Morocco, which are poised to benefit from a greener shipping sector, avoid the “resource curse” that too often plagues communities living at the source of global commodities.

None of these multi-pronged negotiations will be easy, as our partners at Germany’s Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) can well attest. A few years ago, NABU commissioned an assessment of two emissions-control areas that had been established in the Baltic and North Seas, in an effort to address the excuses routinely trotted out by the industry as a way to resist making change — for example, that it would be impossible to make their ships run on lower-sulfur fuels, or that extensive overhauls would bring bankruptcy. However, excuses related to a lack of money ring particularly hollow in light of the massive profits racked up by the industry over the months of Covid bottlenecks. The results showed that the reverse was true: shipping companies that had adopted cleaner fuels saw increased profits, and, as a bonus, the port communities involved saw major declines in local air pollution.

Armed with that evidence, NABU turned its attention to the Mediterranean, focusing on the region’s very visible cruise industry. Over the course of two years, campaigners liaised with relevant industry groups in Greece, France, Israel, Turkey, and beyond while collaborating with environmental groups already active in busy ports like Venice and Barcelona. Traveling to cruise ports all along the north shore of the Mediterranean, NABU staffers worked with scientists to measure air pollutants and then held press conferences to share their results. Widespread coverage in the press helped push local and national governments to address the pollution related to their cruise industries and shipping in the region generally. Though it entailed winning support from countries all around the Mediterranean — not to mention navigating the tense politics between Turkey and Israel and the diplomatic fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — NABU ultimately helped convince them to submit a proposal to the IMO forcing ships in the region to use marine diesel rather than high sulfur fuels. They now have their sights on helping to establish an emissions-control area running from Norway and Iceland down to Spain and Portugal, an endeavor that, given the limited number of countries involved, should prove far less daunting.

Last November, the Northwest Seaport Alliance, a partnership between the Ports of Tacoma and Seattle, announced scoping plans for a green corridor with the Port of Busan in South Korea. Los Angeles and Long Beach recently established a partnership with Singapore to put in place a corridor focused on low- and zero-carbon fuels for bunkering, as well as on digital tools to support zero-carbon ships. An Australia–East Asia Iron Ore Green Corridor is in the works, and the U.S. Departments of Transportation and State have teamed with Transport Canada to establish a green corridor for the Great Lakes region. Last year at COP27 in Egypt, some of our partners launched the Green Shipping Corridor Hub, an online platform aimed at supporting the further deployment of green corridors around the globe.

Recently, Jesse Fahnestock, a project director at the Global Maritime Forum, based in Copenhagen, marveled over the momentum that we’ve seen in just the last 24 months. In addition to the establishment of so many green corridors, industry groups and national governments have signed a range of declarations and ambition statements related to finance, freight, and infrastructure. Jesse recalled how in March 2022, he and a few colleagues had traveled to Spain at the request of the U.K. government to speak to a group of industry representatives about the green corridor concept. They’d presented their ideas before an audience of 50 or so and were met by nothing but blank stares. Last month, after a year of continued engagement with port operators, cargo companies, local officials, and others, Jesse and his colleagues returned to Spain. While attending a session in Bilbao, they looked on in astonishment as an industry consortium formed right there on the spot, with participants agreeing to take on exactly the sorts of commitments that he and his team had floated to deaf ears one year earlier.

In July, the IMO is set to announce a new range of decarbonization goals, which presents an opportunity for the organization to align its ambitions with those of the Paris Agreement and to clarify the milestones it intends to hit in order to do so. In the meantime, green corridors will continue to provide the industry with a way to move forward in an arena that can otherwise feel unmoveable. The concept has given people across the industry as well as in government a sense that they can do constructive things now, without having to wait for the IMO or the global rollout of new fuels and vessels.

Back in 2021, the Dutch company trying to wriggle the visible-from-space Ever Given free from its perch in the Suez compared the vessel to a “beached whale” — an apt image for an industry long stuck in its polluting, law-flouting ways. After six days, though, a team of salvagers relying on a combination of tugboats, large-capacity dredgers, and high tides managed to finally push, pull, and dig the behemoth from its predicament. Overhauling an industry as massive as global shipping might feel like an equally Sisyphean task, but I’m confident that given the same sort of all-hands-on-deck approach we witnessed in Egypt, we’ll be looking at a carbon-free sector sooner than anyone might imagine. ◊